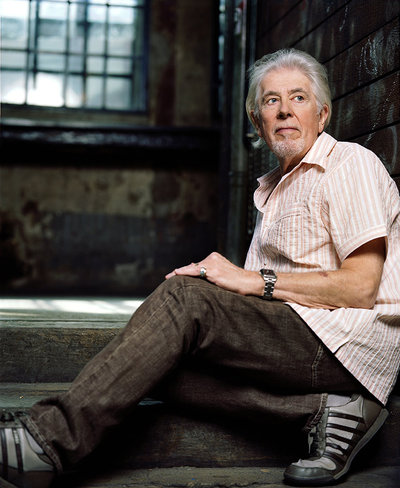

“People come to our shows because they want to hear what we do. It’s irrelevant what we play,” the 80-year-old Brit bluesman says, circumventing any specific commentary on his tour, his band, his audiences — anything.

Mayall’s live shows, famous for their classic grit and wild improvisation, have been the defining characteristic of his career, but he isn’t keen on discussing even that.

In a gravelly tone, he describes this year’s international tour with his band, the Bluesbreakers, like so: “We go in and we do our job.”

It’s difficult at first to see the charm in Mayall’s unimpressed, Cockney gruffness — and yet, as they have for almost 60 years, huge, dutiful audiences show up at every stop to offer their foot stomps and head shakes of approval to the man who, it seems, has played with them all: Eric Clapton to Mick Fleetwood to Harvey Mandel.

Mayall is a touchstone of blues music, and his respect is to be earned, not assumed.

In many ways this marks Mayall as representative of a lost generation of musicians, one that cashed in on skill and innovation rather than image. It cannot be argued that what Mayall does onstage is anything less than surreal. He fittingly describes his songs as “just tools to hang your hat on,” and the rest is created new each time, all snarling harmonica and full-strummed guitar riffs.

Mayall isn’t really an egoist, either, since he belongs to yet another dying breed of musicians: those who place themselves in a long-standing lineage of tradition.

The blues is, by definition, a collaborative genre, and Mayall is forthright about how much he owes to his influences, the first of which he noted was the late B.B. King.

“They’re subliminally involved in everything I do, without me thinking about it,” Mayall says.

He’s iconic of his genre, which chooses to speak with black keys instead of words. Mayall’s far from warm and fuzzy, but then again, so are the blues.

John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers play 7:30 pm Tuesday, July 14, at The Shedd; $14.50-$36. All ages. — Isabel Zacharias