London, England, 1622; William Shakespeare has been dead for seven years.

Six years prior, in 1616, Shakespeare’s rival, playwright Ben Jonson, had published a collection of his own plays. Emboldened by this publication’s success, the former business partners of Shakespeare, John Heminges and Henry Condell, follow Jonson’s lead and set about anthologizing Shakespeare’s work.

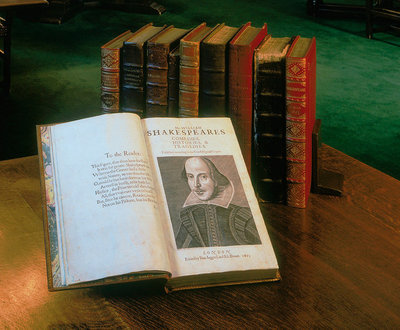

This anthology became Mr William Shakespeares [sic] Comedies, Histories & Tragedies, or now more commonly known among scholars as The First Folio.

On the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. is sending The First Folio on tour.

About 230 copies of the folio are thought to exist, and the Folger Shakespeare Library owns 82 of them — the world’s largest collection.

The University of Oregon, in collaboration with the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, submitted a bid to host one of these folios in October 2014. In February 2015, they found out they won.

The First Folio! The Book that Gave Us Shakespeare exhibit will appear at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art on the UO campus Jan. 6 through Feb. 7. To complement the exhibit, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival will host a free gala featuring scenes from King Lear Jan. 7 at the Hult Center.

Visitors can see the book opened to Hamlet’s immortal “To Be or Not to Be” soliloquy.

“In addition to the touring exhibition,” says Johanna Seasonwein, senior curator of Western Art at the Schnitzer, “we will be exhibiting three additional books and eight prints, all from the UO Libraries Special Collections.”

“The books include Shakespeare’s second and fourth folios,” Seasonwein continues, “and playwright Ben Jonson’s collected works. The prints illustrate different ways that artists have interpreted Shakespeare and his plays.”

Bruce Tabb is a UO Special Collections librarian who has spent time with the folio. “The books themselves as artifacts are just beautiful,” Tabb says, but it’s Shakespeare’s influence that is most notable.

“Shakespeare, as a name, is just universal,” Tabb explains. “How he inspired the art and artistry, literature and everything — that influence, he just touches everything.”

“I hope this will inspire some people who have never seen Shakespeare to go see Shakespeare,” Tabb says.

Risky Business

Four-hundred years ago, the folio project was a financial risk for Heminges and Condell.

At the time, theater was considered a lowly form of entertainment, a common and vulgar diversion for the masses unworthy of preservation or literary scholarship. The importance of authorship was a new concept.

“[Theater] had been thought about kind of the way we thought about television in the 1970s — something that would rot your brain and led to social disorder,” UO English professor Lara Bovilsky tells EW. Bovilsky helped put together Eugene’s bid to host the exhibit.

The First Folio had a limited print run of an estimated 750 copies and is the only source for 18 of Shakespeare’s most enduring works including Macbeth and The Tempest.

Original copies of The First Folio now sell for millions. In its day, a folio is thought to have sold for about one British pound. In 2014, a previously unknown copy was discovered in a French library, untouched for 200 years. In 1998 a copy of the folio was stolen from Durham University in England.

Due to its potentially enormous value, for security purposes the Folger Library does not disclose the provenance of the folio that will appear in Eugene.

“It contained nearly all of his plays,” Bovilsky explains, “and half the plays in it had never been published during his life.”

“We wouldn’t have those works without the book,” Bovilsky continues. “We might not think as highly of Shakespeare, or be as interested in Shakespeare, if we didn’t have a sense of the size and depth of his collective work.”

Four editions of Shakespeare’s folios work were printed in total. The books were a commercial success, in many ways creating the modern publishing industry. Due to the printing processes of the time, each folio is unique, right down to the typos that appear in one copy but may not appear in another.

“It’s not the first book published in English that makes a claim that works of theater are important,” Bovilsky says, but “that was a very new idea.”

“Ben Jonson had published many of his own plays and other writings,” she adds. “It’s that book that gives Shakespeare’s business partners and friends the idea to publish [Shakespeare’s] work,” Bovilsky says.

However, Bovilsky says, The First Folio is the first large-scale volume of solely English plays ever published.

A Universal Influence

Knight Library’s Special Collections and University Archives will host a companion installation to First Folio! called Time’s Pencil: Shakespeare after the Folio.

“It’s intended to take the visitor through the centuries after The First Folio gets published,” Bovilsky says.

“That’s a really interesting story,” Bovilsky says, adding there will also be a display on the history of Shakespeare in Eugene. “We have a lot of material in there that takes people through the topsy-turvy evolution of Shakespeare.”

Bovilsky says the two exhibits show the many facets of influence from one writer. “Arguably the most influential writer in history,” Bovilsky asserts. “Oregonians can get a better sense of that history, but also these exhibits are full of 400-year-old objects. It’s exciting to come so close to these objects and get a sense of how that history is still palpable.”

Curator Johanna Seasonwein agrees history is taught best with tangible objects.

“Our visitors will have a chance to see an original object — not just a facsimile or a digital photo — of an important work that helped to shape our understanding of Shakespeare and his plays,” Seasonwein says.

“So often when I am working with students during a class visit to the museum, they want to know if the work that we are looking at is ‘real,’” she continues. “In the digital age, objects can still have significant power for viewers when they encounter them.”

“Students always get very excited when they understand that they are looking at a real object made by a person in the past,” Seasonwein adds. “Seeing an authentic object like The First Folio not only creates a bridge to another point in time, it can also facilitate cross-cultural dialogue and understanding.”

For more information about First Folio! The Book that Gave Us Shakespeare and companion exhibits, visit jsma.uoregon.edu. In collaboration, Oregon Shakespeare Festival hosts “Sweetly Writ,” a free gala performance of scenes from King Lear 7 pm Saturday, Jan. 7, at the Hult Center. Tickets are required; contact 682-5000.

What’s in a name?

“The term ‘folio’ refers simply to the size of a book,” says Bruce Tabb, librarian at UO Special Collections.

“Folio means that a sheet, when run through the printing press, contains text of four pages or two leaves,” Tabb explains, “depending on whether text is printed on both sides of the paper.”

“Once run through,” Tabb continues, “the sheet is folded once, producing two leaves of text if the text is not printed on the verso, or four pages of text if text is printed on both the recto and the verso.”

“In the four Shakespeare folios,” Tabb says, “there is printing on both sides of the page, the recto and the verso. While this has little to do with the importance of the first Shakespeare folio, it does explain the term and why it is applied to the first four printings of Shakespeare plays: their size.”