At first glance, Cuba doesn’t quite seem like a developed nation but it’s not exactly Third World either. In Havana, even off the tourist track, there tends to be air conditioning and indoor plumbing, and ordinary people in public places look healthy and reasonably well fed. True, most of the cars whizzing past are battered relics of the 1950s but, thanks to Cuban resourcefulness, they’re still running — often powered by a newer Toyota or Soviet-era engine hidden under the hood.

Cuba is fun. There’s plenty of music, sometimes in unexpected places — usually featuring guitars playing the sensual dance music called salsa — plus lots of local rum, inviting beaches and an abundance of cultural events and nightspots. Shopping is limited by American restrictions on what tourists can bring back to the states. At last report, most goods brought back, limited to no more than $400 worth, have to be primarily “educational materials” like posters, books, postcards and paintings. A hundred dollars’ worth of rum and cigars is permitted but many apparently innocent things like T-shirts are forbidden. For years, tourists from other countries, mostly Canada, have gotten to buy things that Americans could not.

You rarely see beggars. If you’ve rambled around the Third World as I have, you’re only too familiar with the sight of skinny, raggedly dressed, barefoot kids, stunted by malnutrition and endemic disease, begging from any American who passes by. But when I visited Cuba on a recent trip, I never saw anything like that. In Kenya, when I traveled there years ago with a friend in the Peace Corps, he wouldn’t let me wear my backpack on my back. “Hang it in front and hold onto it,” he advised me. “Thieves slit them open and help themselves to the contents.” I’ve gotten similar advice from old hands in more desperate parts of Latin America. But before I visited Cuba this past September, everyone assured me that Cuba was safe, safer than Miami.

At that time American credit cards couldn’t be used in Cuba so, like many of my companions on this “people-to-people” delegation authorized by the U.S. government and organized by a nonprofit organization active in Latin America called Witness for Peace, I turned over much of my cash to our group leader for safekeeping. Then I stashed my walking-around money in my fanny pack, confident that no street criminal would contrive to snatch it off me.

Still money dealings, like many other aspects of life in this sunny country, are complicated — maybe uniquely so. “No es facil” (it’s not easy) is a local byword. Tourists and local people use two different types of currency. Tourists use CUCs, short for Cuban Convertible Pesos, while Cubans use the “general peso.”

A CUC costs a little more than $1. But there’s no plausible exchange rate between the CUC and the peso. For instance, a ration book issued by the Castro regime to subsidize its citizens entitles a Cuban shopping at a government store to buy a month’s allotment of staple foods for a family of four for the supposed peso equivalent of two CUCs — less than $3 U.S. This includes a moderate supply of rice, beans, cooking oil, sugar, coffee, some meat, vegetables and fruit. (Shoppers can use additional pesos to buy more at other stores or directly from the farmers who produce them.) Meanwhile, one pound of unremarkable cheese from Poland — dairy products are in short supply — cost me two CUCs at a privately run store.

Since many products are unaffordable prices with general pesos, many Cubans are eager to obtain American dollars or CUCs by dealing directly with tourists — driving a cab or working in a fashionable restaurant or hotel. The government provides some (reportedly dreary) hotels and restaurants, but Airbnb accommodations in people’s homes and privately run and owned restaurants called paladares are growing in number, often run by local women. But odd problems trouble Cuba’s Communist government with its concern for equality and basic services for all.

Before Fidel Castro took over, all blacks were barred from the University of Havana. Today education is free for all Cubans from pre-school to trade school or university, and the nation has one of the highest literacy rates in the world. High quality, free medical care is available to all, but limited by shortages of supplies caused by the 55-year-old U.S. embargo on exports to Cuba and, indirectly, through an American system of high fines and prohibitions imposed on other nations, international banks and corporations which did business with Cuba.

Before I left the states, Witness for Peace sent me a list of “suggested donations” we might bring with us: simple school supplies, personal care products, first aid and over-the-counter meds, and more specialized medicines and medical supplies. We were also advised to bring along flashlights, extension cords or similar low-tech items which we might have use for on this trip.

In spite of the embargo, life expectancy in Cuba is about as high as that in the U.S: roughly 78 for men and 80 for women. Since “the triumph of the revolution” in 1959, life for Cuba’s least privileged citizens has greatly improved. But Cuba’s racial mix has changed drastically and, despite the nation’s egalitarian policies, darker-skinned people of color are still particularly likely to be poor. Recent history helps account for this.

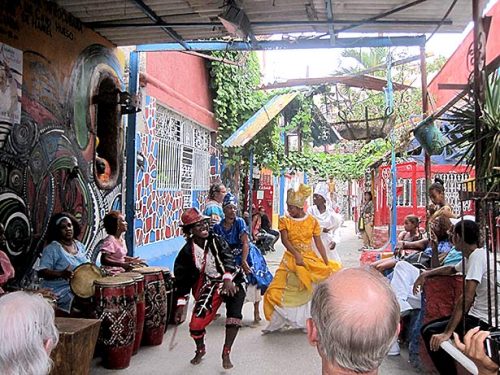

In 1959, when Fidel and his guerilla army liberated the nation from its hated dictator, Fulgencio Batista, there were 6.9 million Cubans. Sixty percent of the land was owned by American corporations and another 20 percent of its economy was dependent on American money, primarily arriving via the tourist trade. Cuban beaches and joie de vivre, expressed by popular Afro-Cuban music and dance, were strong lures. But so were gambling in Mafia-run casinos and prostitution — virtually the only career, aside from work as a domestic, then open to poor girls aiming to leave the countryside.

At that time the population was about two-thirds white. Since then, despite its much-publicized out-migration, Cuba’s population has risen to well over 11 million, and the ethnic balance has tipped from majority-white to majority-brown. Reports from nationsonline.org and factrover.com, among others, say Cubans today are 51 percent mulatto or mestizo, 37 percent white, 11 percent black and 1 percent Chinese. So what happened?

From the start, a whopping 96 percent of all Cubans who emigrated to the U.S. after Castro took over were white. They tended to be more prosperous and privileged. Much of their wealth had been invested in land and real estate — but one of the first things the revolutionaries did was expropriate great tracts of land and limit each household to no more than two homes. This infuriated the wealthy while it made lots of other Cubans happy. Today, 85 percent of the population own their own homes (some are apartments). No doubt millions of renters who suddenly became owners were delighted and their gratitude strengthened their support of the new government. But other, unintended consequences flowed from this transformation.

The Cubans who moved to the U.S. after being shorn of assets turned their bitterness against the Castro administration into a secular religion. They became a significant force in Florida politics and the Republican Party.

Beneficiaries of the emigrés’ land and residences started having more children. A population explosion on the island ensued — but only for a while. Now the birth rate in this country where contraceptives and abortion are readily available is one of the lowest in the world.

As years turned into decades, the condition of the housing stock deteriorated. Given the American embargo, it was hard to get building supplies. For almost 30 years, the Soviet Union helped to counteract this situation, but after the USSR imploded in 1990, the Cuban people faced a decade of severe privation called “the special period,” in which they were forced to improvise to survive until Cuba found new ways of supporting itself.

This Caribbean nation has a long history of excellence in medical care. Wealthy people from elsewhere in the region — and even from remote countries in Africa and elsewhere — sometimes travel there for serious operations. Nowadays Cuba sends many of its fine, locally trained doctors abroad and trades their services for badly needed imports like food and oil. Cut off from the West’s artificial herbicides, pesticides and fertilizers, it has become a leader in organic agriculture and has developed “green” medicines and vaccines that it also exports. Among its other exports are nickel, sugar, seafood and honey.

The concern of its politically undemocratic but idealistic one-party system that no class of individuals own much more than the rest has impeded obvious solutions for some of its problems. Particularly, the deterioration of its housing stock. Until recently the government didn’t allow artisans like electricians, carpenters and plumbers to set up their own businesses to make needed repairs for others for a fee. Even after they reluctantly approved, they didn’t permit independent businessmen to hire people aside from family members to work for them. Meanwhile the nation’s private homes and apartment buildings fell deeper into disrepair.

Paladares — appealing, privately owned restaurants, family owned and operated — fill a public need all over Cuba but thus far it’s unthinkable that any family or company might set up a chain of such restaurants. And here we run into other consequences of earlier racial patterns.

Since whites dominated business before the revolution, whites remaining in Cuba are more likely to have the skills and inclination to set up their own businesses now. Second, since almost all those who left Cuba were white, virtually all remittances from relatives abroad have come and continue to come to white Cubans, supplying them with capital. Finally, enterprises like restaurants are often set up in private homes. Many large, comfortable, conveniently located homes remain in the hands of white families who remained in Cuba. The Airbnb accommodations thriving all over the nation tend to be offered in just such homes.

Six days after our delegation landed in Cuba, Pope Francis arrived to universal acclaim. Much of the pope’s enthusiastic welcome stemmed from the notion that he’s played an important role in the recent thaw between this country and the U.S. One widely accepted story claims that after the death of Nelson Mandela in December 2013, when dignitaries from around the world converged on South Africa for his funeral, the pope convinced Barack Obama and Raúl Castro, Cuba’s president since 2008, to shake hands and, thanks to the pope’s influence, negotiations between our two countries have continued ever since.

|

| Transportation can still be primitive in rural areas |

Just days after the pope’s visit to Cuba and before his meeting with President Obama a few days later, we learned that, thanks to new actions by Obama, credit cards soon would be usable, U.S. telecommunications companies would be authorized to build towers in Cuba, and limits on remittances from the U.S. would be removed. In a dramatic change of policy, U.S. banks were permitted to facilitate leases and loans formerly forbidden and vital to international trade.

Polls tell us that 73 percent of Americans favor restoring normal relations between the U.S. and Cuba. American farmers would love to sell their produce to this market just 90 miles from home. American corporations are eager to establish footholds in this Caribbean neighbor with a well-educated, healthy, yet low paid population where Canadian, Brazilian and Spanish companies already are working with the Cuban government on projects.

On Dec. 11, American officials announced that direct postal service would soon resume between Cuba and the U.S. Since Jan. 27, U.S. banks have been allowed to provide direct financing for most American exports to the island nation. Still up for discussion is how to settle claims for the property seized by the Castro regime 55 years ago, though Cuban diplomats argue that damage to their economy caused by the American embargo greatly exceeds the value of any property expropriated.

No one expects these issues to be resolved immediately. Still whenever they are, let’s hope that normalizing relations will lead to beneficial economic and political reforms in Cuba. Let’s hope, also, that the regime’s positive achievements — like free health care and education for all — will survive.

|

| A working class neighborhood in Havana |

Cuba’s birth rate at 1.47 is one of the lowest in the world. Informal conversations with students our delegation cornered on the University of Havana campus described an uninhibited youth culture where young people couple off freely, but due to the housing shortage, they are forced to move in with the parents of one or the other. Living with virtual in-laws in crowded settings seems to work for a while but adding a baby to the mix may not. With contraception and abortion readily available, after a few months or a few years couples tend to break up, still childless.

As a recent New York Times article put it, “a shortage of available goods and a dearth of sufficient housing (encourage] Cubans to wait to start a family, sometimes indefinitely.”

Most of those eye-catching vintage taxis are owned by the government. The state runs a taxi agency and its own repair shops but it also rents some cabs to licensed, self-employed drivers. In a liberalizing trend, Cuba now permits mechanics to be self-employed and small businesses to supply parts. The typical car, whatever its chassis, is likely to contain parts from many countries.

One evening, three of us from our delegation decided to go to Old Havana for a taste of local nightlife. The conference center in whose dorm we were staying kindly phoned for a cab. One arrived, we got in. But to start it, the driver had to open the door on his side, climb out and then, reaching in with his hand on the steering wheel, run alongside the car until the motor coughed back into action and he could leap in to take us to our destination. On our way back, the next cab we took started OK — but there was no seat at all in front on the passenger’s side. The three of us, including one long-legged man from Minnesota, crowded into the back seat. “Never had so much leg room before!” he said.

Most Cubans aren’t Catholic. Despite their distant heritage from the Spaniards who colonized their island and converted its natives, most Cubans don’t practice this religion. Many are atheists — a philosophy that until 1992 was pushed by the communist party. Tiny minorities are Jews, Buddhists, Muslims or Bahai. About 400,000 are affiliated with Protestant denominations. Far more practice Santeria, a hybrid religion derived from West African beliefs cloaked in a thin veil of Catholicism to satisfy slave masters. Priests in this faith, who may be women as well as men, claim to offer the individual believer spiritual guidance, cures for personal problems (sometimes using sympathetic magic), healing (often through the use of local herbs) and mediumistic contact with the dead.