In 2014, Crystal Webb left Alabama, landed in Eugene and moved in with a friend to kick her opiate and crystal meth addiction.

Making the decision to get distance from an environment in which she found herself intertwined with drugs and dealers was a significant step if she wanted to get clean. Webb says she locked herself away for a month and slept.

“It was painful, but so was using, so I guess maybe I might have been a little conditioned,” she says. “When using, every come-down was painful, so I knew what to expect, just not how long it would take.”

Webb says she slept on the floor for about six months because she was scared of sleeping in the same bed as the woman who is now her wife, as Webb suffered from night terrors, withdrawal and hypnagogic hallucinations.

After coming to Oregon, Webb started working with Occupy Medical, a free universal health care nonprofit, where she met her wife. As she became more involved in the Eugene community by helping people suffering from addiction, Webb encountered a man passed out under a tree with a needle in his arm. Seeing “something like that, it takes you back, and you relive that misery over and over,” she says. “And that’s where cravings come into play, which I still get.”

But Webb says she’s lucky. She has brain damage from an overdose of methamphetamine and the prescription drug Dilaudid, but her doctor says it’s healing. And as her brain heals, Webb has noticed changes. “Just out of the blue I’ll be so sad; I could cry all day long.”

Webb is only one of millions of opiate addicts across the country and thousands in Lane County. On April 21, Prince was found dead in his home, and when an autopsy was conducted the following day, the 5-foot-3-inch singer weighed 112 pounds, according to the Associated Press. Prince died from an overdose of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid.

In 2014, Lane County saw 156 overdose deaths and had “a fatal overdose rate of 15 per 100,000 residents,” according to NorthPoint Recovery Center.

Prescription opioids are derived from the opium plant. “Some opioids, such as morphine and codeine, occur naturally in opium, a gummy substance collected from the seed pod of the opium poppy,” according to the Center for Addiction and Mental Health. When the chemical structure is altered, it becomes a semisynthetic and forms opioids like oxycodone and hydrocodone. Synthetic opioids like fentanyl are not derived from poppies, but heroin is also synthesized from the poppy plant, according to the National Institutes on Drug Abuse.

As the amount of overdose deaths from prescription and non-prescription opiates has escalated in what has become a silent epidemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Oregon Health Authority and local health professionals are changing their prescription practices and ways to treat chronic pain.

In June, the Oregon Health Authority announced it will adopt the CDC’s guidelines for prescribing opiates for chronic pain. The CDC’s newest prescription guidelines for doctors notably change the outdated view that addiction was only possible for “high risk patients” to “opioids pose risk to all patients.”

|

| Dwight Holton Speaks at a summit to end drug abuse |

The Growth of a Silent Epidemic

Not only was kicking the habit hard for Webb, but beating addiction comes with a plethora of obstacles. Ten years ago, Webb was living in Gulf Port, Mississippi, working as a market-training manager for Taco Bell and was in a long-term relationship with her then-partner. Hurricane Katrina ripped the roof off of her Mississippi home — and leveled the Taco Bell — so she relocated to her mother’s home in Mobile, Alabama.

Webb’s decade-long relationship ended abruptly, and she began taking prescribed pain medications for a back injury. Vicodin and Percocet helped Webb’s pain, and she says Xanax and Soma, a muscle relaxer, were later prescribed.

A few years later she met and began dating a new partner who “had a very similar past as mine. We both had traumatic childhoods and we clicked, and it was a recipe for disaster because neither of us knew how to support each other. We triggered each other.”

Webb says nearly everyone in her Alabama social circle had access to prescription opioids, used them or sold them.

Opioids saturate Oregon. With a population of 3.9 million, 25 pills are available every year for every man, woman and child, according to the Oregon Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, a program run by the Oregon Health Authority. That’s 100 million pain killers prescribed annually, and from 2012 to 2013, Oregon was number two on the list of non-medical use of opioids, according to the National Survey on Drug Use.

In Oregon, 43 percent of overdose deaths are caused by prescription opiates, according to an Oregon Health Authority statement. The statement acknowledges the increase in prescription pain medication since the ’90s.

In February, the Oregon Coalition for Responsible Use of Meds hosted the Lane County Summit to Manage Chronic Pain and Reduce Prescription Drug Abuse. Lines For Life Executive Director Dwight Holton says there was an audible gasp in the room when he presented a specific slide. Lines for Life is a nonprofit dedicated to preventing substance abuse and suicide.

The slide showed numbers from study published in 2014 by Express Scripts, a pharmacy benefit management company: “47 percent of those on opioids over 30 days are still on them three years later and 60 percent of those on opioids longer than 90 days are still on them five years later.”

Holton served briefly as Oregon’s U.S. attorney and left that office to run for state attorney general in 2012. While in the U.S. Attorney’s Office, he worked on policy changes with Lines for Life. He says in 2010, when working as a federal prosecutor, he thought that it was heroin that was responsible for more than 400 overdose deaths in 2009 as reported by State Medical Examiner Karen Gunson. “The medical examiner told me to guess again,” Holton says. Prescription opioids were responsible — not heroin.

Sam Quinones tells EW, “This has been a quiet epidemic.” Quinones is the author of Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic, a nonfiction narrative that chronicles the history of the medical advertising industry, the use of opiates prescribed to treat pain and the evolution of opiate addiction that made room for the easy delivery of Mexican heroin throughout the U.S.

In Dreamland, Quinones details a series of meetings where doctors met in Milan to discuss treating terminally ill patients with opiates. The World Health Organization called morphine “an essential drug” for treating cancer pain and also “claimed freedom from pain as a universal human right.” According to Quinones’ research, this changed medical and public opinion; therefore, if someone sought medical attention for pain, that person should be believed by doctors who should then “prescribe accordingly.”

The opiate problem has evolved over the past several decades. “It used to be that half of the country was supplied by Turkey and Burma and it was very expensive, very weak and hard to get,” Quinones says. Then a “total paradigm shift takes this pill epidemic to awaken the trafficking that has made them readjust their production.”

Quinones says that huge amounts of heroin are now coming from Mexico. “It doesn’t get cut, it’s really cheap, really prevalent, really potent, and Oregon has become a big hub.” Another problem is black tar heroin; Quinones found that “when people get out of jail or rehab they go back to this stuff [because] it’s much cheaper.”

According to the CDC, prescription opioid deaths have quadrupled since 1999 with 165,000 people dying between 1999 and 2014 — 14,000 deaths in 2014 alone. The Oregon Health Authority says, “In Oregon in 2013, more drug overdose deaths involved prescription opioids than any other type of drug, including methamphetamines, heroin, cocaine and alcohol.”

Holton says, “People have been dying from opiate addiction for a long time now.” Holton has seen the epidemic shift, too. “For the longest time we did not use opiates for pain treatments precisely because of a concern for addictiveness — we’ve known about the addictiveness of opiates for hundreds of years,” he says.

Despite that knowledge, another pivotal moment in opioid prescription practices that was discussed at the Lane County Prescription Summit was Dr. Hershel Jick’s 1980 study, “Addiction Rare in Patients Treated With Narcotics,” in the New England Journal of Medicine. Holton says aggressive marketing and perpetuation of the myth that opioids can be non-addictive are some of the reasons behind the current epidemic.

So as opiates spread uncontrollably across the country and here in Lane County — paving the way for heroin because of its cheap cost and interchangeable high — why has it taken decades for people to talk about it?

“Stigma,” Holton says. “For many years people did not understand the breadth of this problem because of the stigma.”

Quinones says, “There’s no public violence. Doctors prescribing opiates thought it was a good idea and parents of overdoses were ashamed.”

He adds, “I had a hell of a time finding parents who wanted to talk about it.”

Kicking the Habit

As Webb struggled with addiction in Alabama, she was hit with another blow. “Losing my insurance plan was how I moved from opiates to meth,” she says.

The drug abuse worsened for her girlfriend, too. “A year later, I almost died. A year and a half later, my girlfriend died.” Webb says her partner died of a combination of meth and Roxycodone, an immediate-release version of oxycodone.

The day before her girlfriend overdosed, Webb brought her a chicken sandwich, a soda and clean needles. “I’m glad that the last time we were together it wasn’t a fight,” she says. The day after the funeral, Webb was on a one-way flight to Eugene with the goal of getting clean. But she got high by injecting crystal meth before takeoff.

Holly Peters is the intensive services director at South Lane Mental Health. She watched her father suffer after a back injury and the death of her mother. He was prescribed opiates for his injury, and she says that when it came time for him to taper off, he didn’t have the support and resources that were necessary. Peters began drinking and taking opiates and heroin at the age of 14 and eventually watched her father lose his struggle with addiction.

In his research, author Sam Quinones discovered that a drug trafficking operation out of Xalisco, Mexico, known as the Xalisco Boys, developed delivery operations that made it easy for addicts to get their hands on dope. An informant in Dreamland noted that the new heroin cells operate “like a pizza delivery service.” The drivers navigate around cities to deliver the black tar heroin, which is stored in balloons the drivers carry in their mouths.

Quinones tells EW that part of the business model includes hanging out near methadone clinics. “These guys just made an art of it — going to a town, getting an addict to go to a town and an addict will take them to places,” he says. In his book, Quinones writes that the Xalisco Boys saw methadone clinics as “game preserves,” where they’d lurk and catch people at clinics to provide them with “free samples.”

Methadone treatment is also highly stigmatized, according to Linda Hill, a spokesperson at the Lane County Methadone Treatment Program. “An important role for clinic staff is to provide advocacy and support to patients.”

Hill says, “Methadone is a synthetic opioid that suppresses withdrawal by acting on the opioid receptor sites in the brain. It is an important, lifesaving “medication assisted treatment” option for those struggling with opioid addiction.”

Methadone treatment breaks down like this: Most new patients are required to show up daily to receive their dose of methadone; one-to-one counseling and other treatment services are provided. With demonstrated stability patients can eventually earn “take-out” privileges and come to their clinic less often, according to Hill. She says that most methadone clinics embrace the dual focus of harm reduction and abstinence.

Holly Peters kicked her addiction because what she “learned was that opiate addiction is a mental, emotion and physical experience, learned that my recovery needed to be an experience, too.” After she completed a recovery program, she earned her bachelors degree in psychology and her master’s in social work.

“My recovery needed to replace all of those things,” she says. “That’s what we are trying to do at our program by taking a holistic approach so people can get that without having to reach our to an illicit substance.”

And users always face the risk of getting caught. More than 800 meth and heroin cases were filed in a seven-month period in Lane County, according to Chief Deputy Attorney Erik Hasselman. But he says those numbers don’t necessarily indicate a spike.

“We’ve been working with very limited number of lawyers,” Hasselman says. The voter-passed 2013 Lane County jail levy “also had some money for the DA’s office built into it — we were able to prosecute with that money. We had not been prosecuting the overwhelming majority of the drug charges for a few years.”

And if a person is carrying a pipe or a baggie with trace amounts detectable, they can be cited for possession. Eugene police officers carry narcotics identification kits or NIKs.

However, Hasselman says first-time offenders cited for possession have options. “Our first objective is to make sure they are afforded the opportunity to engage in treatment that would happen through Lane County Drug Court,” he says. “When people successfully complete drug court by graduating, the charges are dropped and they never get probation, have their Oregon driver’s license suspended, or serve jail time.”

If a person opts out of going through drug court, the DA’s office follows the typical prosecution track. “Possession charges can be class B and C felonies. A judge’s authority is limited to felony sentencing guidelines, so simple possession charges can never go to prison for just possession, unless there are substantial quantities involved.”

Webb knows several people who have been arrested repeatedly for drug use, and she’s still learning the ins and outs of the drug court system. “I do have the thought that jail does nothing for addiction because I’m sure, just like any other jail, drugs are there already,” she says.

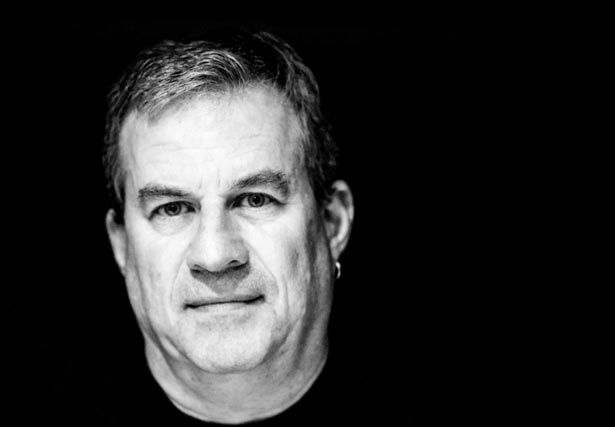

|

| Sam Quinones, author of Dreamland — The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic |

Recognizing a National Health Crisis

As people continue sharing their stories — and as more information about overdose deaths becomes available — the nationwide conversation about the epidemic is slowly changing. In 2014, the CDC announced that overdose deaths have surpassed car accidents as the leading cause of accidental death in the U.S.

On April 4 of this year, Gov. Kate Brown signed House Bill 4124, which allows pharmacists to dispense the overdose reversal drug naloxone and “requires the Oregon Health Authority to disclose prescription monitoring information to practitioner or pharmacist.” In February, President Obama requested $1.1 billion to combat the opioid addiction problem.

Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden sat down with EW recently and expressed disappointment in the Comprehensive Addiction Recovery Act of 2016 (CARA), passed by the Senate earlier this year and the House on July 13, calling it a half measure. Wyden proposed two amendments to the bill — taking $75 million set aside for drug manufacturers to continue making “abuse deterrent” pills and instead helping addicted pregnant women who enrolled in Medicaid, and more transparency on advisory panels that make prescription practices recommendations to the Food and Drug Administration. Both were voted down.

The bill passed, but Wyden says, “Congress shouldn’t be taking a victory lap.” He adds that the efforts were largely driven by the right.

“Who are you going to give this money to?” he asks. “Women who are enrolled in Medicaid with limited means are struggling to fight addiction, get their lives back on track, or are you going to give a windfall to drug companies?”

Wyden says striking down both of the amendments he proposed “are to me reflective of how so often powerful special interests prevail against the public interest.”

He says the next step to addressing this crisis is for citizens to contact their elected officials and make their voices heard. “[T]here have been landmark studies at Johns Hopkins talking about how 80 percent of the people who are hooked to heroin and opioids who needed treatment couldn’t get it, and I said I want everybody to know [that] under what the Congress just did last week, those treatment lines are not going to get much shorter.”

The senator says enforcement alone does not eliminate addiction. “You’ve still got a person in the community whose addicted, so you have to make the three parts work in tandem: There is enforcement — important role for it — but treatment and prevention are equally important, and if you don’t put the pieces together you’re not going to have a good strategy.”

Wyden also wrote a letter to the president of the National Academy of Medicine regarding two members of its advisory board who had links to opioid manufacturers. According to the Associated Press, four members of the panel were dismissed for having ties to the pharmaceutical industry because its members are supposed to be properly “vetted for financial ties that can influence their judgment.” Wyden says, “They have removed a handful of people from at least one of the advisory boards and it’s largely attributed to the pressure that we put on them.”

According to CDC spokeswoman Courtney Lenard, “Prescription opioids can help with some types of pain in the short term but have serious risks.” She says they are an important part of treating pain for cancer or hospice care. “However, studies are not available to indicate whether opioids control chronic pain well when used long-term.”

Holton says, “For decades, doctors were told that there is little risk of addiction and much potential benefit for treatment of chronic pain.”

He continues, “It turns out that is totally wrong — there is limited potential benefit, and a very significant risk of long term dependence.”

Dr. Paul Coelho, who works in pain management in Corvallis, says Holton is absolutely right. “Over the ensuing 25 years we’ve seen opioid overdose deaths, addiction and now heroin use rise to epidemic levels. It was a colossal mistake and we are paying for it now.”

Coelho says “PHRMA definitely played — and continues to — play a role in the opioid crisis.” He refers to the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America and the 2007 New York Times article that covered the $600 million settlement in which Purdue Pharma paid in fines for “misbranding” OxyContin and pled guilty to “criminal charges that they misled regulators, doctors and patients about the drug’s risk of addiction and its potential to be abused.”

Coelho also refers to a $1.1 million settlement reached in Oregon in 2015. Insys Therapeutics was accused of “deceptive marketing and improper payments” to sell fentanyl, according to The Oregonian.

“Simply put, it is more lucrative for PHRMA to pay off-label marketing sanctions than to risk designing and performing a randomized trial that could disprove that opioids have utility for chronic non-cancer pain,” Coelho says.

The new CDC guideline suggests treating patients with nonpharmacologic therapies like cognitive therapy and exercise and to incorporate those therapies when opioids are prescribed. The new prescribing rule, “start low and go slow,” recommends that doctors begin with the “lowest effective dose.”

According to the new CDC Guidelines for Primary Care Providers, “Studies show that high dosages (≥100 MME/day [morphine milligram equivalents]) are associated with 2 to 9 times the risk of overdose compared to less than 20 MME per day.”

Before Webb became dedicated to decriminalizing homelessness, she says, she thought people living on the streets were just lazy. “I lived comfortably above the poverty line until drugs came into the picture,” she says. “I found it wasn’t so easy for me to get a job once I had a drug habit.”

She walks through downtown Eugene to get to work and says she used to joke that the streets were her office. She says she’s been practicing being a peer-support specialist before she trained as one. “Often times I walk around handing out water and granola bars just to get familiar with new people.”

September will mark two significant events for Crystal Webb — she’ll be celebrating two years in Eugene and two years of being clean.

“I consider Eugene a healing town — if you want to get healthy you can do it here; you just have to not be afraid to ask for help.”