A massive earthquake, a toxic chemical spill, a huge forest fire. If a disaster strikes the McKenzie River, it strikes Eugene’s sole source of drinking water. There is also the possibility of a “malevolent attack on the water system,” EWEB says.

In these worst-case scenarios the Eugene Water and Electric Board (EWEB) has only one or two days of drinking water in its 94 million gallons of storage during the summer months.

And to put it simply: Without water, people die.

At the very least, health, safety and even the economy are placed in jeopardy without a reliable and voluminous water supply.

EWEB General Manager Frank Lawson says Eugene, with the 180,000 people the utility serves, is the largest city in the Pacific Northwest that has a single source for its drinking water.

While the idea of a massive disaster hitting Lane County may seem farfetched, the state government’s “Oregon Resilience Plan” says there is a 15 to 20 percent chance the Willamette Valley will experience a very large earthquake within the next 50 years.

In January 2014, 300,000 residents in Charleston, West Virginia, couldn’t drink or bathe in their tap water for almost a week after about 10,000 gallons of a chemical called “crude-MCHM” spilled into the water supply from an old storage tank.

Also in 2014, the city of Toledo, Ohio, had no backup when a fertilizer-fueled algae bloom in Lake Erie fouled its water supply. This left 500,000 people without clean water to drink and is an ongoing summertime problem.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency’s “Planning for an Emergency Water Supply,” the “current approach to post-disaster water supply in the United States is bottled water.” But the EPA says that “at a certain disaster scale, duration or remediation-recovery period, this strategy becomes unsustainable.”

In other words, when the big earthquake hits, waiting for a truck to arrive with bottles of water just isn’t the wisest strategy.

EWEB has set out to establish a backup water supply for Eugene — also known as a redundant supply — by 2022. And the utility plans to take that water from the Willamette River. Water experts and river advocates agree that it’s a good idea.

But there are some barriers EWEB must cross before it can get that second source of water. Gaining the right to use the water is well underway, but land, cost and even public perception that the Willamette’s waters are lower quality than what Eugene gets from the McKenzie are all factors.

The Right to the Water

At a Nov. 10 stakeholders’ water forum at EWEB discussing the second source plan, Jeff Althouse of Oakshire Brewing raised an eyebrow at the mention of introducing water from the Willamette River into Eugene’s water supply. Oakshire makes a Watershed IPA that celebrates the McKenzie River’s pristine water.

Water is the number one ingredient in beer, and the water from Eugene’s McKenzie watershed is so pure that little to nothing has to be done to it before it’s used in the brewing process — breweries in many other areas have to purify their water. The less treated the water, the better it tastes. “Beers reflect the region where they are made,” Althouse says.

The water forum discussed the plan with Oakshire and about two dozen large commercial water customers and public agencies. Representatives from Veneta — which buys water from EWEB — the city of Eugene and PeaceHealth, among others, were there.

But beyond discussing whether Willamette River water tastes as good as what comes out of the McKenzie, EWEB first needs to have a right to the water.

Users can’t just randomly pull water from rivers; under state law, Oregon’s water is publically owned and users must be given a right to it. Watermaster Michael Mattick says that EWEB holds a number of water rights.

The utility has three rights on the McKenzie, two of which are “perfected.” The water rights system in the West assumes that water needs to be used, and to “perfect” or certificate a right, it must be put to beneficial use.

Mattick, part of whose job it is to cut off users if the rivers run below a certain level, calls the second source plan a good idea — better not to have all one’s eggs in one basket, he points out.

Those first two rights allow the withdrawal of nearly 194 million gallons per day. A third right for an additional 118.2 million gallons per day is in progress, and it is the reason why EWEB sells water to Veneta.

In its 2012 “Water Management and Conservation Plan,” EWEB also discussed selling water wholesale to Creswell, Coburg and Junction City.

Travis Williams of Willamette Riverkeeper says of EWEB’s water right and second source plan: “It seems like a prudent idea to have that backup. The only question I would have over time is to what degree it could migrate to a primary water source as the region’s communities grow?”

Jeannine Parisi with EWEB’s public affairs office stresses that the effort to get a second source is not about amassing yet even more water. “We have ample water rights on the McKenzie far into the future while at the same time, water usage is flat or declining even with population growth.”

Parisi says the second source project “is all about having a diversity of supply to mitigate against natural disasters and/or major equipment failures and allow more flexibility to take critical facilities off-line for maintenance.”

And Parisi says EWEB agreed that its cumulative water rights would remain the same — the Willametter water right does not increase the total amount of water EWEB can use.

Mattick says that the state issued a Willamette water permit to EWEB on Feb. 28, 2011, for 30.9 cubic feet per second with a “priority date” of Jan. 3, 2011. Four points of diversion are listed in the permit — four places EWEB can pull water from. The original water claim dates back to the 1880s, Mattick says, but if the Willamette River were to be adjudicated — meaning all the claims to water on the river are established — EWEB could have lost that pre-1909 right.

While other rivers in Oregon have been adjudicated, pre-1909 water right claims on the Willamette River are unadjudicated, and Mattick says they may not be adjudicated for decades, leaving pre-1909 claims, permits and certificates uncertain. EWEB’s 2011 permit might be a junior permit, but it’s a safe bet for the future given the uncertainty.

Parisi says EWEB plans to use the point of diversion on the permit furthest upstream to take water — before the river really starts to run through town — to help avoid the major stormwater outflows in downtown Springfield and Eugene.

Priority dates on water rights matter because they mean that those with older rights have priority over newer rights. “The permit language for the Willamette restricts our withdrawal during very low water conditions,” Parisi says.

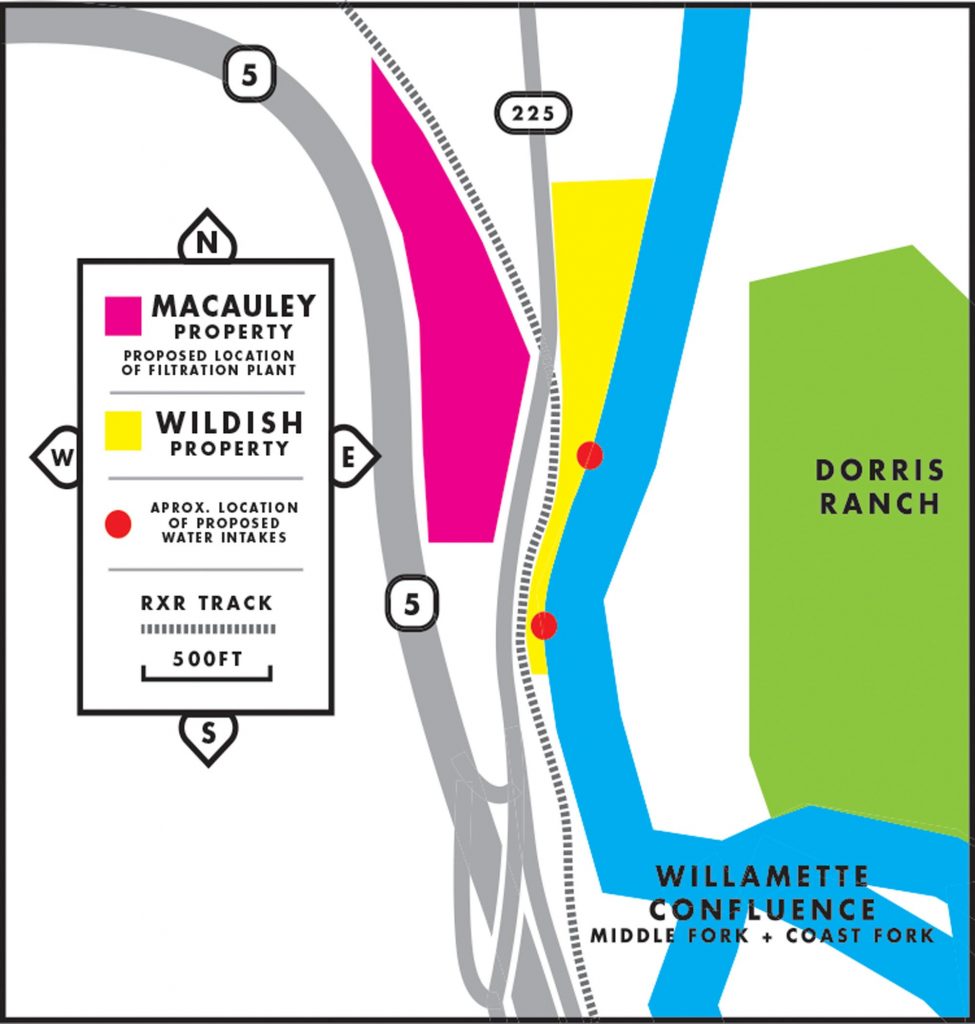

EWEB will pull its water from just below the confluence of the Coast and Middle forks of the Willamette River.

At the Nov. 10 water forum EWEB’s water engineering supervisor, Wally McCullough, said that water from the Willamette would in the future enter the system at a rate of one to two million gallons per day. And Parisi says EWEB would be capable of treating the full 19 million gallons a day that it has the right to.

It has not yet been determined where in EWEB’s water system it would enter.

You can’t get a permit for water you are not using, Mattick says.

A Point of Diversion

On a chilly November day, the Willamette River flows swiftly by the graveled road near the planned intake. Canada geese paddle in the river and a red-tailed hawk wings its way through the trees.

Fans of nude sunbathing might recognize the area where EWEB plans to pull water from the Willamette. It’s upstream from Glenwood near the area known as the Willamette Confluence. Glassbar Island, once home to nudity aficionados, is nearby.

Informal access to Glassbar on foot — it’s a state park that can only be reached by boat — was cut off in 2013 when restoration work in the area began. That restoration work is a key element in cleaning and cooling the water in the Willamette River.

Unlike the McKenzie, touted for its clean, clear waters, the Willamette has been maligned as polluted for decades. The majority of that pollution, however, is downstream in urban areas such as Portland. Sarah Dyrdahl of the Middle Fork Watershed Council says the Middle Fork largely flows through protected lands with its headwater in the Willamette National Forest. One of the headwaters is Waldo Lake, “some of the clearest, cleanest water in the world,” she says, and the other is in the Diamond Peak Wilderness Area.

“From a water quality perspective, the Middle Fork water is quite nice,” Dyrdahl says.

She says that Oakridge, West Fir, Lowell and Springfield draw from the Middle Fork. Adding Eugene “seems to fit.” Dyrdahl says EWEB is a good steward of its water source.

“It’s fantastic if we get all our utilities to think in the same vein,” Dyrdahl says, “proactively protecting the source before it’s degraded.”Karl Morgenstern, EWEB’s source protection coordinator, says the utility is working on coordinating water source protection efforts with cities that pull from the Willamette downstream, like Corvallis, Wilsonville and Sherwood.

The Coast Fork of the Willamette tends to be warmer and shallower, but Morgenstern says he is still studying the dynamic between the two rivers and which water dominates at a given time.

The Middle Fork tends to dominate, but a flood event could affect that. The Coast Fork has a couple dams on it, and the Middle Fork has Hills Creek, Lookout Point and Dexter reservoirs; flows are controlled by the Army Corps of Engineers.

Fishermen tend to release resident fish, such as bass caught from the Cottage Grove Reservoir on the Coast Fork, because they pick up naturally occurring mercury. But “mercury has not been detected in any of the 18 water samples collected at the proposed intake site over the past three years,” Parisi says.

Morgenstern says that because Hwy. 58 and a rail line run alongside the Willamette, it faces possible oil and coal cars in addition to the tanker-trucks that run next to it and along the McKenzie River on Hwy. 126. If a tanker were to spill fuel into the McKenzie, the utility could have as many as six hours to fill its reservoirs. Its intake 30 feet below the surface may not even be affected, he says.

One distinct advantage of EWEB’s planned intake site is its proximity to the Willamette Confluence where restoration work has been underway for several years. Replanting riverside forests mitigates algae conditions by shading and cooling the water. The riparian trees also naturally filter sediment, reducing turbidity (cloudiness) and heavy metals, EWEB says.

The Nature Conservancy (TNC), Friends of Buford Park and Mt. Pisgah, Oregon Parks and Recreation and Willamalane Park and Recreation District all have restoration projects along the confluence. The projects reconnect the river to its historic floodplain through connecting ponds and back channels, controlling invasive species and restoring habitats.

Treating the CostJill Hoyenga, EWEB water resource and system planner, says one of TNC’s projects, Pudding Ponds, which reconnected gravel pits to the river, showed a reduction in air and water temperature in the area in only two years. Cooler water reduces the changes of algae blooms that affect water quality.

“It is usually more reliable to have more than one source, but this also can be more expensive,” says Jay Lund, director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at University of California Davis. “Many systems that rely on a single source will invest in some local storage so as to be able to survive for some days or weeks, or longer, if the source is interrupted,” he adds.

That Eugene’s water source will someday be interrupted is not in question — the Cascadia Subduction Zone quake is going to happen. It’s a question of when.

Increased storage would still leave EWEB with only one filtration plant, and in order to have true redundancy, the second water source also needs its own treatment plant.

And no matter how clean the water in the river, it still needs some treatment. According to the presentation given at the water forum by Hoyenga, Lawson, McCullough and other EWEB representatives, testing at the intake location since April 2013 show the “water quality is in many ways remarkably similar to the McKenzie River intake,” though water treatment will have to take into account higher turbidity, algae/algal toxins and something called geosmin, which gives soil that nice earthy smell, but can make drinking water taste foul.

EWEB paid Barney and Worth professional consultants just more than $160,000 to help undo “100 years of ‘polluted Willamette’ headlines” that “have etched a public perception of the river as a potential threat to public health — even though in other parts of the U.S. and world, the upper Willamette would be considered near pristine.”

Back in August 2015 the EWEB board approved purchasing the narrow strip of land between the Willamette and Franklin Boulevard where it runs north-south for about $62,000 from Wildish Land Co. The deal also involved a land swap that gave Wildish a parcel near Armitage Park. That deal gave EWEB the land needed for the water intake — there are two possible water intakes along that strip. Hoyenga says the land there is not prone to liquefaction in the case of a major earthquake — a good thing for a water transmission line.

On west side of the property, uphill from the river and wedged between Glenwood Boulevard, there is another section of land, this one owned by the Macauley Family Trust. It is the site where EWEB would like to place a new, state-of-the-art water treatment plant.

However, after the trustees declined EWEB’s $961,000 offer for the undeveloped industrial zoned land, EWEB began the condemnation process last April in Lane County Circuit Court. Under condemnation, land can be taken by the government via eminent domain and the owner is given just compensation for the land — basically private property is taken for public use.

Hoyenga says the proposed location for a plant is above the 500-year flood plain, hopefully protecting it in case one or more of the dams on the river were to give way in that looming catastrophic earthquake.

EWEB currently has its Hayden Bridge plant on the McKenzie River in Springfield. A second treatment plant, in addition to the second water source, gives EWEB further redundancy — the utility has a backup if the Hayden plant were to fail.

The new Willamette filtration plant would treat detected as well as anticipated substances in the water. So Parisi says, while mercury has not been detected, the plant would be able to treat it.

As McCullough discussed at the stakeholders’ meeting, the plant would use several processes — clarification, ozonation, filtration and disinfection to treat the water. The new plant would be more up-to-date than the Hayden Bridge plant, but Lawson says that the older plant, built in the 1950s, would also be up for improvements.

The total cost for the new filtration plant, replacement and renewal as well as system maintenance has a preliminary estimate of $70 million. Customers have actually already begun to pay for it — EWEB says that small, steady price increases began in 2014 and part of that initial increase goes into a reserve fund. There will be annual 2.6 percent increases from 2018 to 2026, the utility says.

EWEB argues that in 2017 its water bill will remain lower than cities such as Junction City, Coburg, Portland and Seattle. In a 2015 customer survey, 62 percent of customers “are somewhat or very aware of Eugene’s potential water supply issue,” 90 percent think a second source is important and 63 percent “support some increase to pay for a second source.”

As Kathryn Schulz writes in “The Really Big One,” her 2015 The New Yorker article that brought the Cascadia Subduction Zone to mainstream attention, the Pacific Northwest is vastly underprepared for the earthquake that is going to hit. “The odds of the big Cascadia earthquake happening in the next fifty years are roughly one in three,” Schulz writes. “The odds of the very big one are roughly one in ten.”

An earthquake will hit, and as climate change advances, droughts and forest fires loom. Moving chemicals and fossil fuels along rivers endangers them. And we need water.