James Baldwin is one of my all-time heroes. His writing, not to mention the mere fact of his life and times, inspires in me a devastating sense of humility, a leveling of intellectual pride that I always experience when confronted by a solitary artist speaking truth at every cost to himself.

Nothing I write could add to or elaborate or enhance Baldwin’s work in the least. He’s that good. Awe is my only response to the furious, righteous brilliance of his words and vision.

And so I quote him here at length: “If Americans were not so terrified of their private selves, they would never have become so dependent on what they call ‘the Negro Problem.’ This problem, which they invented in order to safeguard their purity, has made of them criminals and monsters, and it is destroying them. And this, not from anything blacks may or may not be doing, but because of the role of a guilty and constricted white imagination as assigned to blacks.”

I transcribed this passage from I Am Not Your Negro, a new documentary directed by Raoul Peck and based on Baldwin’s unpublished manuscript Remember This House, a meditation on racism that hinges on the author’s relationship with, and to, black activists Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., all assassinated.

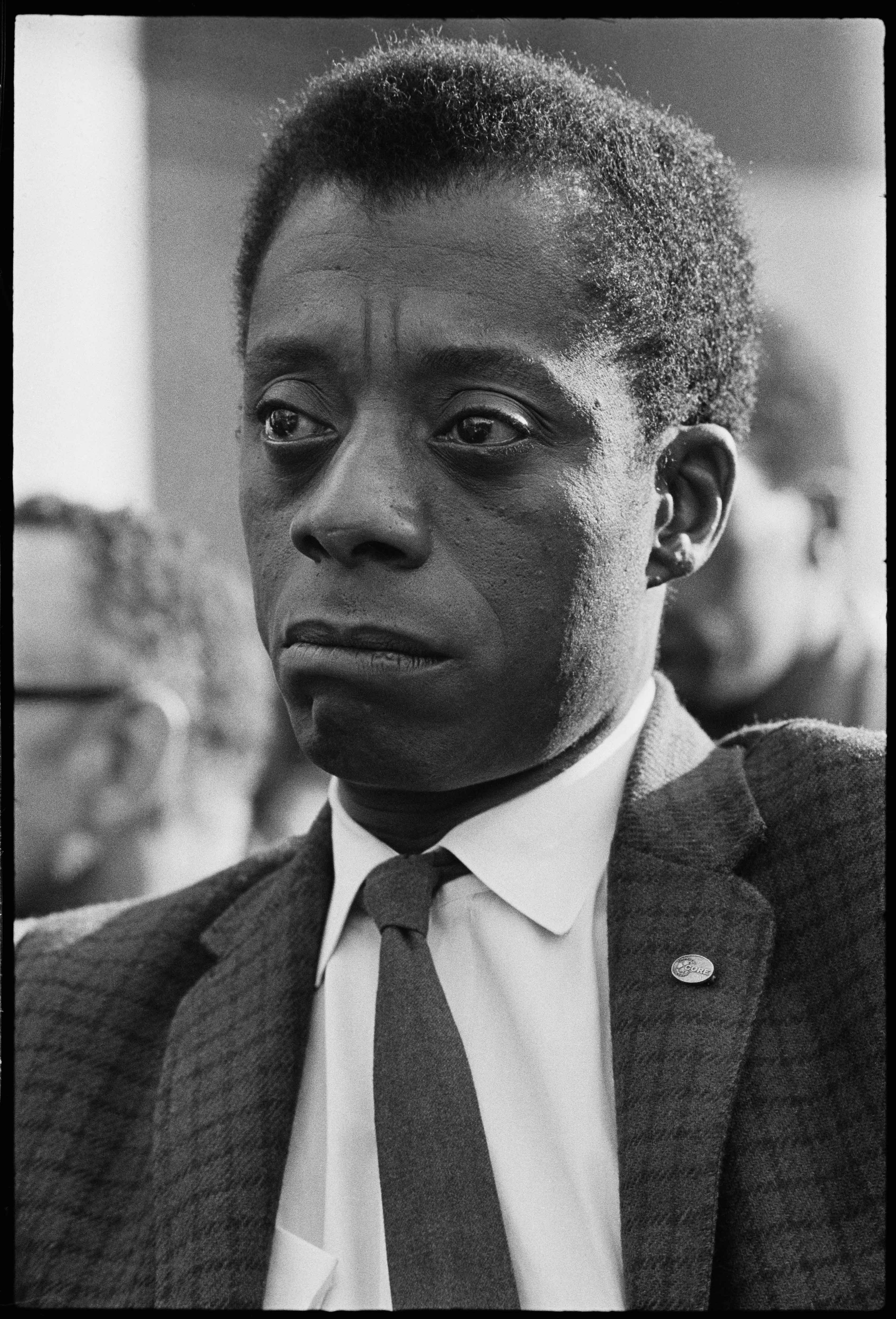

Enlarge

© Bob Adelman

Black, gay and forever an outsider (or, as he calls himself, a “witness”), Baldwin casts a gimlet eye on the entrenched history of racism in American society, and his unflinching insights and reminiscences serve as a sort of spiritual autopsy that lays bare the inner workings of our collective sickness. He holds up a mirror and asks us what it is about us that needs to perpetually seek an abstract target for our fear, anxiety and hatred.

Full of archival footage of Baldwin (who died in 1987 at the age of 63) and interspersed with readings by Samuel Jackson, the film traces the development of Baldwin’s growing consciousness as a black man and a writer, from his childhood to his expatriation to Paris and then his difficult homecoming to stand by his compatriots during the civil rights struggle of 1960s.

As ever, Baldwin’s words are beautiful, revelatory and challenging to an excruciating degree. His fury and indignation are tempered by vulnerability and self-searching, and in lieu of condemnation he always seeks to uncover and comprehend the root causes of racism with a generosity scarcely deserved.

To quote Baldwin again, from the 1963 documentary Take This Hammer: “I’ve always known that I’m not a nigger, but if I am not the nigger, and if it’s true that if your invention reveals you, then who is the nigger?”

Substitute “nigger” with “faggot” or “deplorable” or “Muslim terrorist,” and we begin to see the deepest, darkest implications, the timeliness, of Baldwin’s assessments. His claim is that, until America comes to terms with this critical rift at the heart of its so-called democracy — this need to demonize others in order to preserve its own illusory safety and freedom — it is doomed.

Because the basis of all fascism — the basis of all hatred and intolerance, of all evil — is to accuse others of doing exactly the bad you yourself intend to do, and then, when you do it, to call it virtue. Check your own experience for the truth of this.

And for anyone with ears to hear, the insidious implications of Baldwin’s analysis of racism spread ever outward, to address and confront the growing tide of fascism that is seizing hold of this disastrous century. For this reason alone, I Am Not Your Negro is the most important film of the year, if only because it clearly and honestly designates the nature of the disease we refuse to acknowledge, much less attempt to cure. That disease is chronic, as we see every time another black man is shot and another Muslim banned and another Confederate flag flown off an oversized truck in Eugene. And the disease is mortal. (Broadway Metro)