Matt Dye, aka Blunt Graffix, is showing his art in three different places in Eugene. None is an art gallery.

His work is on view indefinitely at Broadway Metro and Blairalley Vintage Arcade, and his test prints are on display at Epic Seconds through Dec. 31.

Blairalley and Epic Seconds are vintage businesses. That matches Dye’s sensibility, since his work often carries an element of homage to things past. He employs dollar bills or tax stamps from the early 1900s, for example, as formats for his subjects: musicians, actors or films. His interest in art began when, as a kid, he admired Stanley Mouse concert posters for ’60s bands like The Grateful Dead.

In those days, concert posters were handmade prints. Dye’s interest in printing was sparked in the most unlikely of places — using a copy machine in the Navy. A copy machine isn’t the first thing that comes to mind thinking of the military, and it might sound strange that a piece of office equipment helped ignite a career in the arts. But copying machines make images. Before computers a copy machine was essential to art departments, cheaper and quicker than the copy camera that required a darkroom to operate.

After Dye got out of the service he followed in Mouse’s footsteps and had a career as a concert poster artist before transferring his skills to another of his passions — movies. The first time I went to Broadway Metro was years before I met Dye. It was to see a movie, and afterward I stayed in the lobby looking at the pictures on the walls. It took me a while to realize they weren’t actual movie posters.

What tipped me off? Dye sometimes recast movies that have already been made. At Blairalley Vintage Arcade they let him do pretty much whatever he wants, he says, and he wanted to wheatpaste a life-sized print of Bill Murray as Han Solo on their door. The print on the door now is the second Bill Solo because the first one was covered with graffiti. The random lettering or tags didn’t bother Dye at first; in fact, he thought it added to the piece.

But when Murray was completely covered, he pasted on the second print.

Why make images of actors in roles they never played? One could answer the question with an academic dissertation on the practice of “appropriation.” But Dye is not an academic. He refers to these images — borrowing a term from the music industry — as “mash-ups.”

He cast his own role as a printmaker, combining his interest in prints and popular culture, with a great deal of success. His studio and his business, Blunt Graffix, are located in Eugene. He has come full circle and is making concert posters again. He exhibits and co-curates shows on a national scale: in San Francisco, New York, Seattle and Chicago.

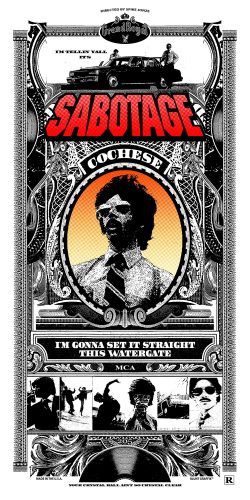

His print Sabotage, on display at Broadway Metro, blends printmaking with a tribute to late Beastie Boys member Adam Yauch, aka MCA. It was submitted in 2015 for an annual MCA Day exhibit held in Connecticut.

The print references a music video the Beastie Boys made, directed by Spike Jonze, to promote their single “Sabotage,” released in 1994. The video was executed in the style of a ’70s cop show, and the print retains that feel. The print Sabotage features MCA, centered in the format and underscored by lyrics from the song: “I’m gonna set it straight, this Watergate.”

Walk over to Epic Seconds, though, and you can view art never meant for exhibition.

The test prints are just that: tests to ensure the actual prints will come out the way the artist wants them. Some have so many layers of testing they carry more weight than an average print. They’re heavy. The layers include Spin Art, a method for spinning paint onto paper or holographic foil.

Dye and his father, a retired metal fabricator, designed a centrifuge especially for spinning by attaching a steel disk to a potter’s wheel.

Benjamin Terrell of Epic Seconds chose the test prints from Dye’s studio to exhibit. Terrell liked the manner in which spinning and testing, none of which was planned, nevertheless added up. The test prints are random, colorful and complex — works of art on their own.

A benefit to seeing Dye’s work at Broadway Metro is you can see a great variety of it. On the downside, you can’t get so excited about it that it makes you want to scream and shout.

I met Dye to talk about his art there and soon after someone at the theater asked us to lower our voices. Oh yeah, people were trying to watch movies inside.

Talking about art in a near whisper, Dye said, “I get bored easily.” Much of the innovation we see in his prints — the spin created by the custom-made centrifuge, the use of foil paper, historic elements — were created to avoid being bored.

About 90 percent of his prints are limited edition, Dye says, but occasionally he’ll revisit a series. When he does he’ll want to add something, to do it differently. Each time he revisits a series it’s an opportunity to learn, to make something new.