Lucinda Parker doesn’t have a contact or use email. In this day and age that seems unusual, but upon seeing her art, it sort of fits.

The art in Lucinda Parker: Force Fields echoes a different era — in fact, several eras. Steeped in traditions of modernism — color field painting, abstract expressionism, cubism — her paintings are large, gestural and dynamic.

Walking through this retrospective, which spans her career from the 1950s up to the 2010s, feels like moving through these parts of art history in the flesh.

Instead of landscapes of Europe, though, we get paintings of subjects closer to home, in the U.S. and particularly Oregon.

Parker earned her BA from Reed College and the Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland. Besides her retrospective at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Salem, she also has work on display at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art in “Visual Magic: An Oregon Invitational,” a show featuring artists who began their careers in Oregon during the 1960s and ’70s.

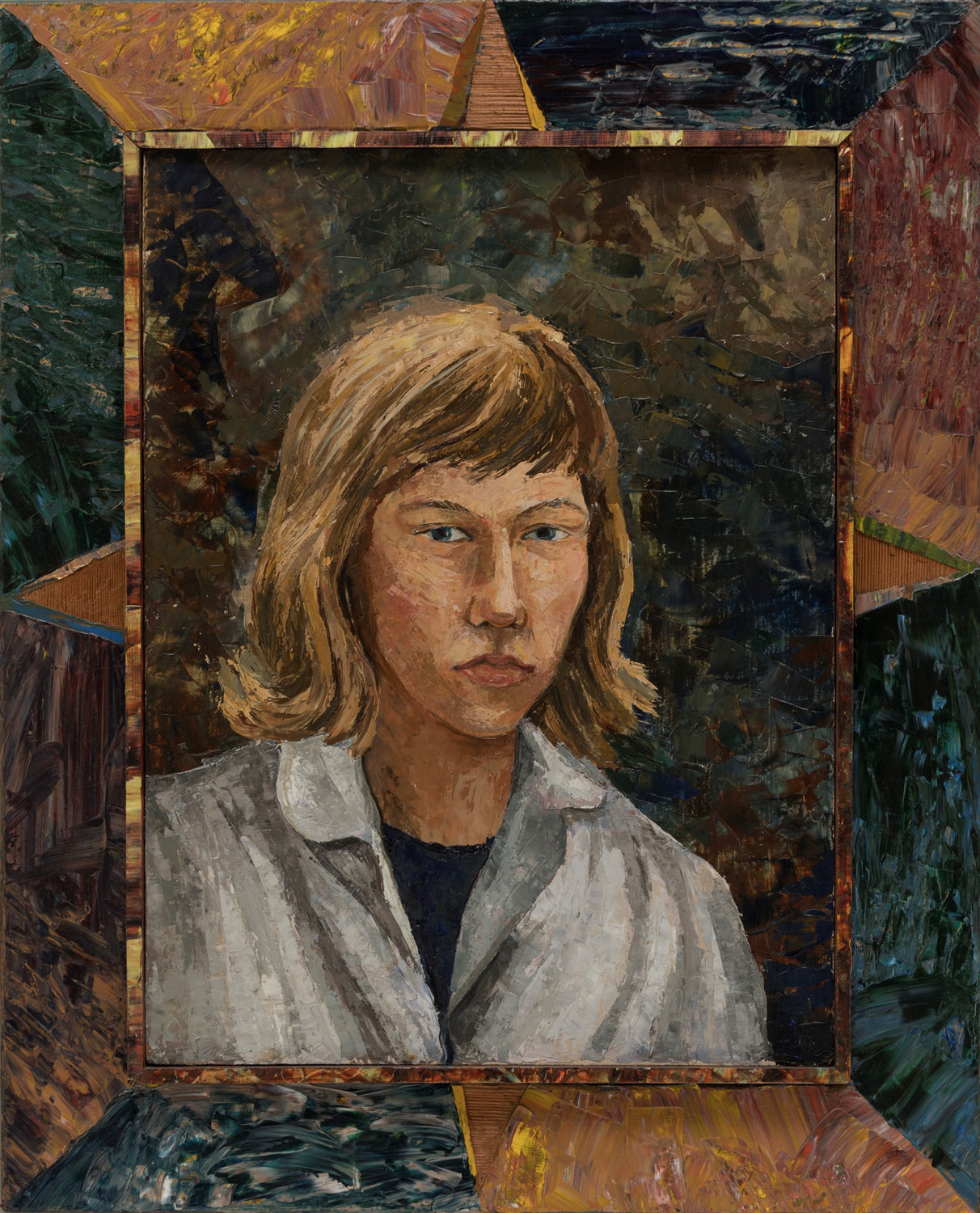

In her teenage years Parker often painted self-portraits, as do many artists at the start of their careers. Even in her most realistic work in the exhibit, “Self-Portrait,” which she painted at about 16, she looks at you through the wonderfully heavy hand of her medium. Parker was still in high school but, even then, she wasn’t timid in her approach to oil painting.

The blurb beside “Self-Portrait” describes the “young artist staring at herself and at what might lie ahead.” Maybe so. Maybe the young artist was thinking about the future, but she has on her face the same expression you see in portraits of Picasso, van Gogh or Rembrandt — that of someone intensely trying to describe what they see.

The only other work from her adolescence in the show, “Waterfall at Garland Pond, Putney, Vermont” (1959-1960), is a landscape. Though realistically approached in terms of recognizable subject matter, the way she applied paint in layers, and at different angles to represent water moving, speaks to the direction she would take as an abstract artist, and later as an artist whose goal was to work toward “meaning.”

That is a term used by her to reference painting recognizable things. The elements of her future work are all here: landscape as subject matter, abstract forms representing nature, the gestural, dynamic and sculptural application of paint.

Titles can be especially important for abstract art. They are a way for the artist to give us a clue. That’s just what Parker says she did with her painting “Cythera’s Gift” (1985).

The reference to Greek mythology is a sample of her fondness for literature. Her titles often play with language. Her 1989 painting “Sur Peint,” for instance, references two languages, French for “painted on” and English for “serpent.”

“Measuring Nature” (1999) is a more straightforward title. For isn’t that what artists do, whether depicting landscapes or portraits, or even abstractions — describe what they perceive in nature, even when that perception is their own response? That painting is hung with “Radicle” (1999), done the same year and with the same dimensions and format. They “go together,” according to Parker.

Enlarge

The museum suggests they are companion pieces as well because of their subject matter: “They both deal with sweeping forms suggesting forces of nature that confront, nonetheless, wiry apparatuses for measure and calibration, perhaps for the harnessing of natural energy.”

The abstract forms in “Measuring Nature” do seem to sweep, as if they’re moving up, on their way to somewhere else. They are barely contained in what appears to be a field of dark space, and the wiry apparatus mentioned above is a frail device next to the comparatively large and looming figures before it.

“Measuring Nature” and “Radicle” perhaps served as the inspiration for the “Force Fields” in the title for this retrospective. They could also serve to inspire our consideration of Parker’s life as an artist. She has been a force of nature since that first self-portrait in the 1950s.

Peering out at herself from beneath the layers of paint as a teenager, up to her most recent cubist-inspired efforts, she has been putting in the effort to measure the world around her, to describe it with color and gesture and design. Exploring genres, moving from abstract to content or “meaning,” experimenting with techniques for applying her medium — her career so far has been bold and on the move, never still.

Lucinda Parker, Force Fields is at the Hallie Ford Museum at Willamette University until March 31. Parker also has paintings in Visual Magic at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at University of Oregon until May 12.