For longtime residents, when you bring up the name Jim Torrey, chances are the June 1, 1997, pepper spray incident will come to mind. On that day, 11 protesters climbed trees at Broadway and Charnelton Street to protest the city’s plan to cut down 40 trees downtown.

Eugene Police Department responded with pepper spray. Three protesters filed a lawsuit, alleging EPD used excessive force to clear the street for tree cutting.

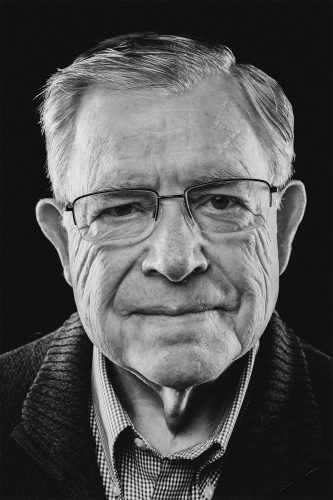

Torrey, then mayor, was seen as responsible for the incident that ended in a lawsuit against the city and which probably prompted someone to vomit on his right shoulder on an Aug. 6, 1997, City Council meeting.

Since then, he ran a failed campaign for the state senate in 2006 and for re-election to the mayor’s office in 2007 — when his opponent Kitty Piercy called him a right-wing Republican.

Despite what liberal Eugeneans see as his problematic background, Torrey has unfinished business on the school board. He wants to ensure Eugene area students get the best education in a time of declining state support while not overtaxing property owners.

Back when Torrey was mayor, he says he made a promise during a State of the City speech to read in every kindergarten class in town. He adds, with a laugh, that was when he learned there were 64 kindergarten classes in Eugene.

But it was the best thing he did because it had an impact on individual lives, he says.

When he went to kindergarten classes, he told kids that if their parents read to them, he’d come back with a goody bag.

Torrey’s kindergarten reading stints are remembered still. He says whether it’s shopping at Costco or getting his car’s side mirror replaced, people have come up to him about how he read to them.

And that’s one of his passions: early literacy. He wants to deal with the gender literacy divide in schools because it can easily snowball into a bigger problem. At high school, if you’re struggling because you never got the necessary reading skills, you’ll struggle to get back on track.

Investing in early literacy requires funding. And that’s something else Torrey says he has experience securing.

At 78, Torrey is one of the many senior citizens in Lane County, a demographic that constitutes 25 percent of the population.

That’s what he says gives him the empathy to hear out seniors who might be uneasy about paying more taxes to support schools through bonds and levies.

“Financially I can afford to pay my taxes. There are some senior citizens who can’t,” he says.

When he went door-to-door last year to push the $319.3- million school bond to voters, he heard some concern from older voters. He told them that he wouldn’t fault them for voting “no” on the bond because of the added financial burden on someone with a limited budget.

The bond went on to pass with 66 percent support of voters in November. Besides a new North Eugene High School, the bond is to fund career technical education (CTE).

“Those classes are important. Keeping those young people in high school who aren’t college bound is important,” he says.

In 4J schools, 89 percent of students who complete two CTE courses are on track for graduation, 15 percent more than students who don’t, according to the school district.

Torrey says he’s heard from parents of students who want their kids to study CTE because it’s a pathway to a good career for those who aren’t college bound. And, to live in Eugene with soaring housing prices, a good paying job is necessary.

“This is not an easy city to live in financially,” he says. “It’s not cheap.”

Schools in Eugene need more CTE. He says if you commit a crime as a juvenile in Oregon, you get sent to Oak Creek Youth Correctional Facility in Albany. In that jail, inmates have access to better vocational education than in most school districts.

“They have the best career technical education facility I’ve ever seen. You can get anything in there,” he says. “Why do you have to commit a crime to be able to have access to that?”

He adds that being a mechanic today, you can’t get away without skills in computers. The momentum to support CTE in schools was evident in the governor’s race.

“Let’s not lose that opportunity,” he says, adding that both boys and girls are interested in pursuing CTE in 4J schools.

Torrey has rebranded himself over time. He left the Republican Party in 2007 for the Independent Party of Oregon. Today he’s unaffiliated because he wants to get away from the excluding factor of political parties.

He mentions the upcoming battle over the Student Success Act — as of press time, it hasn’t been passed by the Legislature. The legislation would impose a $250 plus 0.57 percent tax on a business’ commercial activity that surpasses more than $1 million in goods and services.

Businesses that don’t make more than $1 million are exempt from the tax.

Torrey says he isn’t optimistic about the legislation because it’ll most likely be referred to voters. And that’s where the benefit of erasing political affiliation comes in handy.

“We’re going to need to communicate to all segments of the community,” he says. “I think that’s a benefit I bring to it.”