He was a meteor.

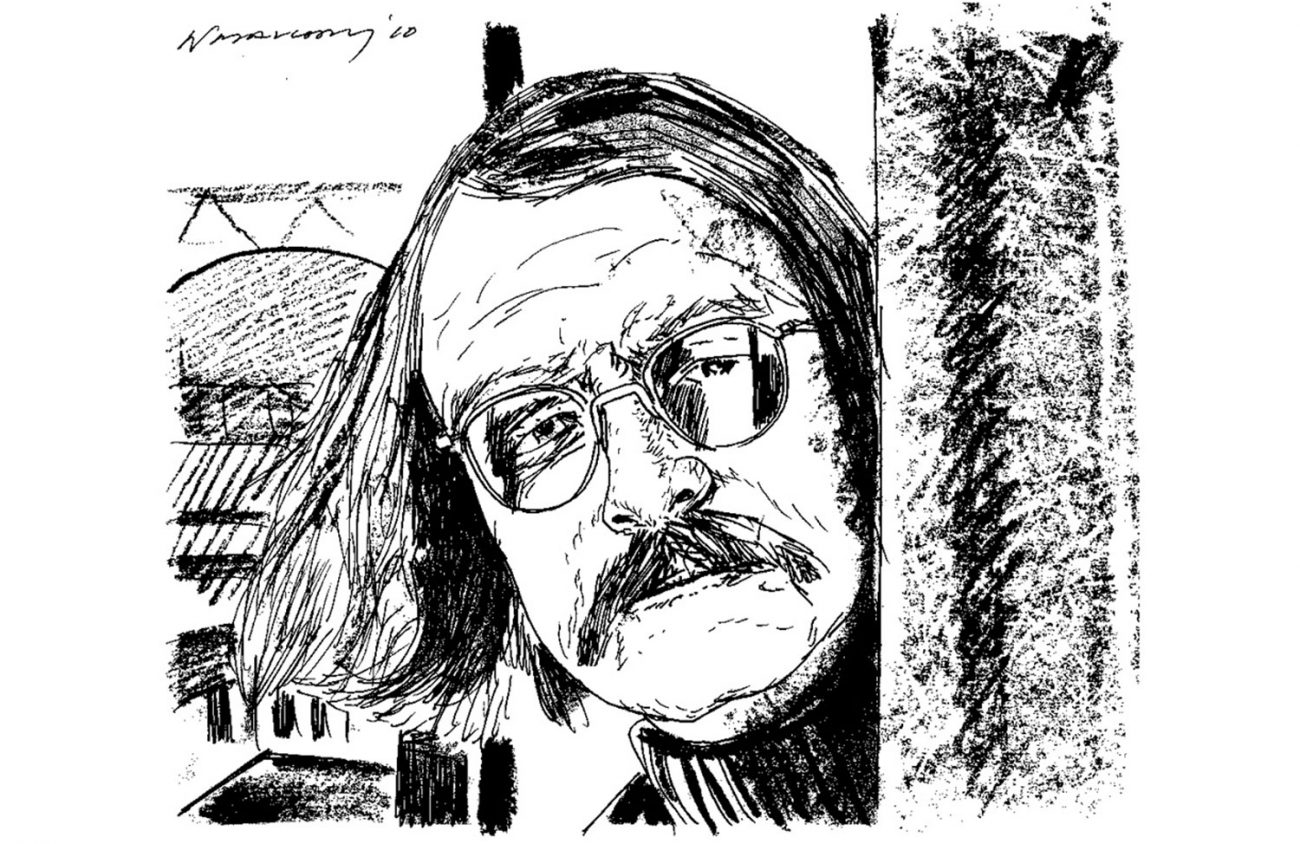

He was an author of such works as Trout Fishing in America, In Watermelon Sugar and The Hawkline Monster, wedged between the Beat Generation and the hippie movement. He showered readers of the 1960s and ’70s with inspiring spare, proletarian ideals in his novels.

He was a poet who foreshadowed the vise-like, smothering grip that technology has over us today in the poem “All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace.”

He was, as biographer and admirer William Hjortsberg noted in Jubilee Hitchhiker, a writer who combined an “easy offhand voice” with “concern for average working-class people, his matter-of-fact treatment of death, and his often-startling juxtaposition of wildly disparate images.”

Then he was gone.

Richard Brautigan — born in Tacoma, Washington, and raised in Eugene — took his life in September 1984. He was only 49. The cosmic arc of the meteor, as well as the potent work ethic that generated 10 novels and other published writings, had been falling to Earth before then.

Sales of his work had dwindled. He battled depression, punctuated by alcoholism, and he had guns. Brautigan killed himself at his home in the Marin County coastal town Bolinas, California.

But Brautigan, the man and his work, have never been forgotten — far from it.

Scholarly work exists that examines Brautigan’s career, and there are volumes of it at the click of a mouse. Family members, too, have stepped into the void, and 35 years after the author’s death, his life still resonates with them.

One is Virginia Brautigan Aste, Brautigan’s 85-year-old first wife. She lives in Hawaii, where she is a substitute teacher and a noted activist and has a skate park named after her — the Ginny Aste Skate Park.

She also was present on the trip through Idaho for Brautigan’s breakthrough novel, Trout Fishing in America (1967). Along with poet Jack Spicer, she helped edit the novel and transcribe Brautigan’s handwritten notes.

Now Brautigan Aste has teamed with Eugene author and poet Susan Kay Anderson to produce a yet-to-be-published memoir, Please Plant This Book Coast to Coast.

The title is a bow to Richard Brautigan’s 1968 poetry collection, Please Plant This Book, his sixth published poetry book. It consisted of eight short poems printed on seed packets. Four of the poems were about flowers. The other four were about vegetables.

Brautigan Aste and Anderson, who met as teachers at Pāhoa High School on the Big Island in Hawaii, will read from the book, perhaps even read some of Richard Brautigan’s poetry, and answer questions on Saturday, Sept. 14, at the Oregon Poetry Association Conference in Salem.

Anderson (with whom I have worked at Egan Warming Center sites) interviewed Brautigan Aste off and on for six years. Brautigan Aste generally keeps a low profile, Anderson says. Many in Hawaii are probably not aware of her connection to the once-famous author.

“They know her as a mother and a grandmother and an activist,” Anderson notes. “She wants to be known for herself.”

Still, in interview transcripts for the memoir, Brautigan Aste is poignant about her marriage to Richard Brautigan, from the wedding in 1957 to the split in 1962 and finally the divorce in 1970. This was especially true after the author gained fame.

“He began drinking heavily and became abusive,” Brautigan Aste says in interview transcripts. “One night, he wanted sex and became violent — I shut him out of the bedroom.

There were these thick wooden doors. The next day I left with [their daughter] Ianthe.”

Yet, there was the nostalgic start of the relationship; the 1951 Plymouth station wagon for the trip across Idaho that would become Trout Fishing in America; and there was the curious, intellectual side to Brautigan that Brautigan Aste speaks fondly of in the transcripts.

“He was very interested in graveyards, gravestones,” Brautigan Aste notes. “Interested in imagining what people’s lives were like — the food they ate, the clothes, 100 or 200 years ago. He was interested in the working people.”

Anderson says, “This is personal and intimate. She wanted to tell her story.”

Ianthe Brautigan Swensen, the daughter, is now an instructor in liberal studies at Santa Rosa Junior College and Sonoma State University in Rohnert Park, California. Her memoir, published in 2000, is titled You Can’t Catch Death: A Daughter’s Memoir.

Brautigan Swensen, along with her husband Paul Swensen, also are executive directors of a screen adaptation of The Hawkline Monster. In June, New Regency bought the rights.

Richard Brautigan’s meteor still has life.

Virginia Brautigan Aste and Susan Kay Anderson will read from Please Plant This Book Coast to Coast from 3:30 to 4:30 pm Saturday, Sept. 14, at the Oregon Poetry Association Conference. The conference is at the Salem Convention Center, 200 Commercial Street SE.

A Note From the Publisher

Dear Readers,

The last two years have been some of the hardest in Eugene Weekly’s 43 years. There were moments when keeping the paper alive felt uncertain. And yet, here we are — still publishing, still investigating, still showing up every week.

That’s because of you!

Not just because of financial support (though that matters enormously), but because of the emails, notes, conversations, encouragement and ideas you shared along the way. You reminded us why this paper exists and who it’s for.

Listening to readers has always been at the heart of Eugene Weekly. This year, that meant launching our popular weekly Activist Alert column, after many of you told us there was no single, reliable place to find information about rallies, meetings and ways to get involved. You asked. We responded.

We’ve also continued to deepen the coverage that sets Eugene Weekly apart, including our in-depth reporting on local real estate development through Bricks & Mortar — digging into what’s being built, who’s behind it and how those decisions shape our community.

And, of course, we’ve continued to bring you the stories and features many of you depend on: investigations and local government reporting, arts and culture coverage, sudoku and crossword puzzles, Savage Love, and our extensive community events calendar. We feature award-winning stories by University of Oregon student reporters getting real world journalism experience. All free. In print and online.

None of this happens by accident. It happens because readers step up and say: this matters.

As we head into a new year, please consider supporting Eugene Weekly if you’re able. Every dollar helps keep us digging, questioning, celebrating — and yes, occasionally annoying exactly the right people. We consider that a public service.

Thank you for standing with us!

Publisher

Eugene Weekly

P.S. If you’d like to talk about supporting EW, I’d love to hear from you!

jody@eugeneweekly.com

(541) 484-0519