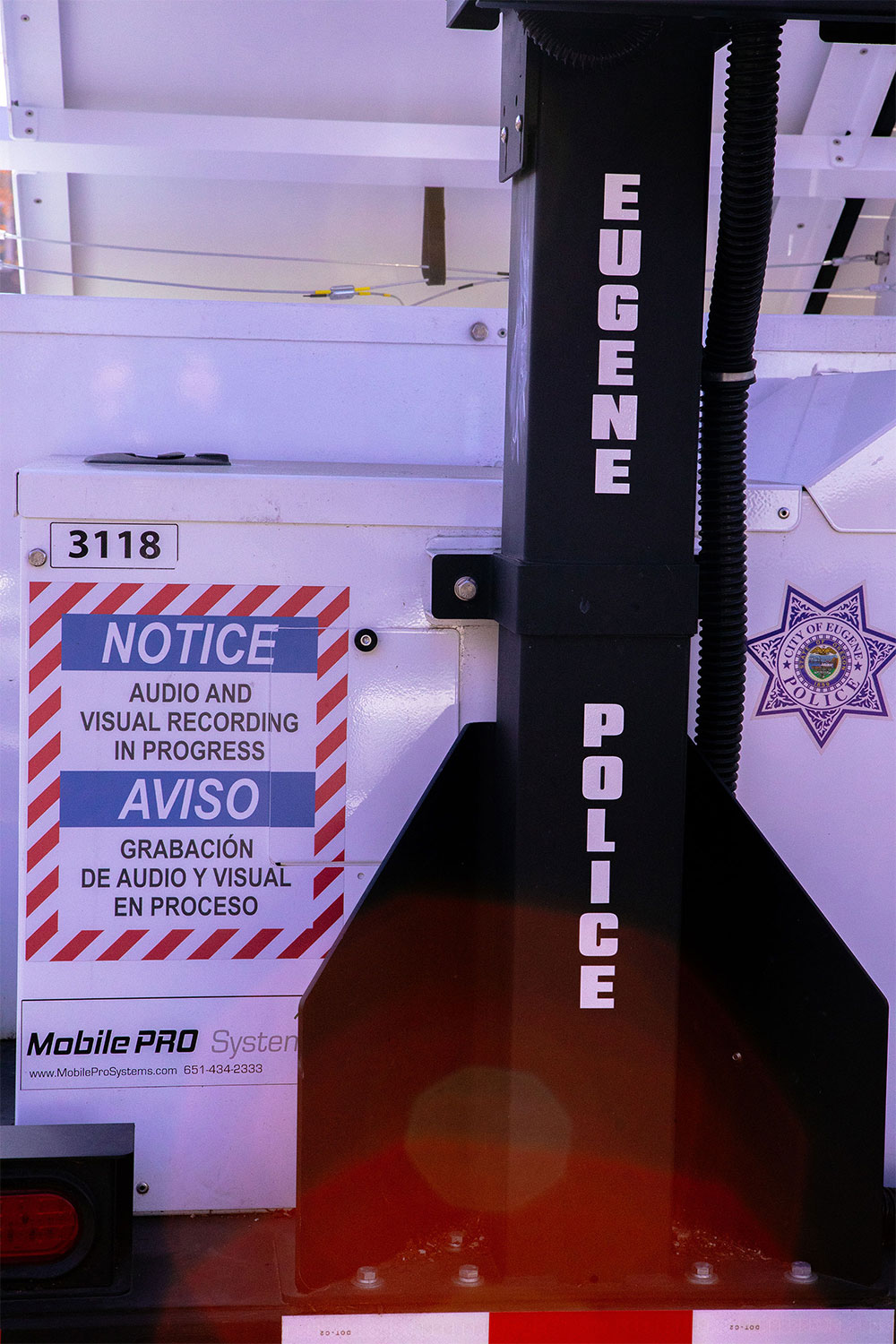

The Eugene Police Department is using one of its three surveillance camera trailers to keep an eye on a group of homeless campers, who, as of press time, are camped across the street from Eugene Weekly’s office on Lincoln Street.

EPD says it’s deploying the cameras based on nearby businesses’ requests to monitor “prohibited camping.” But the Civil Liberties Defense Center (CLDC) says the city is using resources to criminalize the homeless, and the surveillance opens the door to spying on political action.

EW has not complained about the campers, and in fact notified the police there it has no issue with the campers. EW did ask EPD about its offices being on camera due to a possible chilling effect on those who may wish to speak to the paper on background.

Enlarge

Photo by Todd Cooper

EPD has three Guardian trailers, which together cost the city $152,000. The police are using the cameras in an 18-month pilot program that ends April 2020.

Eric Jackson, who leads the group of unhoused campers, is protesting the criminalization of the homeless, and also because he says Eugene Municipal Court does not record its proceedings. Jackson says EPD has mobilized a camera ever since his camp protests began, except when they were located at the federal courthouse.

Melinda McLaughlin, an EPD spokesperson, tells EW that residents have filed several complaints about the campers on Lincoln Street, which is why the police department brought in its surveillance trailer. Businesses in the area around the camera trailer include, besides EW, an engineering firm, a tax prep firm and a children’s daycare center.

Siting the cameras on Lincoln Street is similar to how the police department has responded in other areas with multiple calls for service, such as theft, criminal mischief and drug activity, McLaughlin adds.

Attorney Lauren Regan of the CLDC says people need to pay attention to what the city is doing with the unhoused activists. It’s a slippery slope, because one standard applies to all activists, she adds.

Enlarge

Photo by Todd Cooper

“Rather than looking at it as a homeless protest,” she says, “you have to take a step back and look at what precedent this sets for the right of the people to organize against the state.”

Despite the aura of possible intimidation, Jackson says he doesn’t mind the presence of the cameras because when surveillance is obvious, you don’t have to wonder if you’re being watched in secret. He says he doesn’t feel intimidated by the camera, and actually sees it as protection.

“It keeps everybody a little more honest,” he says, adding that people won’t go out of their way to be stupid if there’s a police camera overhead.

Previously, Jackson says, EPD used the trailer’s LED lights on the camp when it was located outside Buffalo Exchange, making the area as bright as daylight.

McLaughlin says the police trailer’s two movable cameras, which record continuously, are aimed at the “prohibited camping occurring in the area” in Lincoln Street. EW’s property is captured only by the trailer’s overhead fisheye lens that monitors the trailer, she says. McLaughlin says the video isn’t clear, so the camera can’t capture someone’s identity.

McLaughlin says EPD doesn’t notify businesses of the surveillance in advance because the trailers often arrive at the request of businesses that allow the trailers to occupy their private property.

“In this case, it was deployed on a Sunday and on the street due to the continued calls,” she says.

Enlarge

Photo by Todd Cooper

Locating a surveillance trailer outside a newspaper’s office leads to some First Amendment concerns, considering that reporters sometimes work with whistleblowers or those who require anonymity due to fear of personal or job-related repercussions. Even if the video isn’t clear, the presence of a trailer outside the free press can have a chilling effect for a source, Regan says.

EPD previously told EW that it stores the video feed for up to 30 days, and the footage is open for public records requests from the public.

Plus, as Regan points out, the presence of surveillance cameras outside EW’s office makes the police department just look bad.

“It causes mistrust,” she says. “Especially in the political times we are in right now where journalists feel under the gun by the government.”