This time of year — late fall, early winter — can be challenging as far as where to go on a hike is concerned. If you’re like me, it takes a real mental effort to gear up and go outside when it’s cold and rainy. Just because it’s foggy in the Willamette Valley doesn’t mean it is everywhere else.

Surprisingly, it can be really nice on the Oregon coast this time of year. I recommend watching the weather there and then going for a hike where it is usually warmer than the valley — and sometimes even sunny!

The Drift Creek Wilderness is a great destination in the fall and winter. Located in the Siuslaw National Forest in the central Oregon Coast Range near Waldport and Newport, the area highlights our temperate rain forest in its dripping, mossy glory.

And while the fish and wildlife that call the forests of the Coast Range home benefit from Drift Creek’s protected status, at just 6,000 acres it represents a tiny fraction of the vast ancient forests that once dominated the region.

Today, most of this forest ecosystem has been fragmented and damaged by logging and roads.

To find the Horse Creek Trail in the Drift Creek Wilderness, first get to Highway 101 on the Oregon coast. Halfway between Waldport and Newport on the 101, turn east onto North Beaver Creek Road, across from Ona Beach State Park. Go 1 mile to a fork, then stay left. Go 2.9 miles on gravel, then turn right onto paved Forest Road 51 and drive 6 miles. Turn left onto FR 5000 and go 1.4 miles, take the right fork onto FR 5087, and follow 2.8 miles to the end-of-road parking area. No permit is needed to park here, and there are no restroom facilities.

This trail is a total of eight-miles round trip, and loses and gains 1,600 feet of elevation, so it’s not easy. However, you can still have a great forest experience by going just half the distance and avoiding nearly all of the climbing.

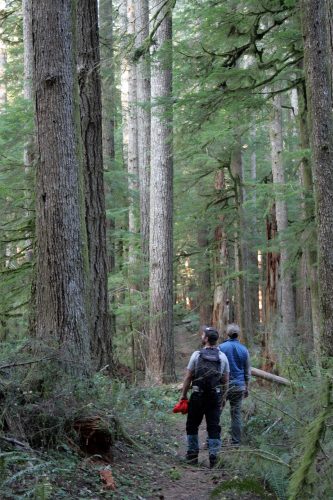

The trail first follows an old road converted to a trail, and reaches the wilderness boundary in half a mile. From here, walk beneath towering western hemlock trees and enter a forest that displays all the characteristics an ancient forest should — snags (standing dead trees), downed logs, patches of young trees and towering giants.

Some areas are denser and younger, recovering from a long-ago fire, while other areas have massive Douglas-fir trees with thick furrowed bark and giant limbs that make perfect nesting structures for marbled murrelets, a threatened sea bird dependent on coastal old-growth forests.

Fall and winter rains make some of the smaller life forms of the forest stand out. Slugs and salamanders need the moisture, and it makes the mosses and lichens that coat nearly every surface in the forest come alive in greens and yellows.

Be sure to look on the ground and down logs to see if any of the forest’s fungal diversity is making an appearance, too. While mushroom gathering isn’t allowed in designated wilderness areas, it’s still fun to see how many different mushroom shapes, sizes and colors you can find.

At about 2.3 miles, you’ll enter a moist area where salmonberry, sword ferns and western redcedars thrive. This is where to consider whether you want to do the whole 8-mile round trip, because the trail begins to descend in earnest. There’s no shame in turning back.

Start to switchback down the slope with views to the south and east out through the forest canopy and Drift Creek’s valley. As you descend, look for short snags sporting miniature gardens, a disheveled mix of salal, red and evergreen huckleberry and young trees.

Pass more wet pockets with vine maples and cedars, and then hit the flattish bench that surrounds Drift Creek, walking past giant Douglas-firs, through tall ferns and past moss-covered logs. At the 4-mile point, reach a creek-side campsite and the turnaround point. Note that Drift Creek itself is only accessible by short, steep, unofficial trails.

Chandra LeGue of Eugene is the author of the book Oregon’s Ancient Forests: A Hiking Guide and is the western Oregon field coordinator for Oregon Wild, where she advocates for the protection and restoration of Oregon’s forests and wild places.