I walked into Courtroom One at the Eugene Municipal Court and sat in the middle of the many rows of benches, took off my coat and scarf, and settled in. Several other people occupied the room. One man sat near the front with someone I assumed was his attorney, and a few security guards sat in the back near another man.

“All rise for the honorable Judge Spence,” the court clerk announced. And we rose. Assistant Judge Marc Spence approached the podium, told us to be seated, and we sat.

This was my first time as a defendant in court. It was not my first parking ticket.

“Next up we have Ms. Perse and Mr. Beckett. She is pleading not guilty to a parking ticket,” the judge said. “Please come forward.”

I walked toward middle aisle and the parking officer, Nate Beckett, met me there. We each moved past the bar and sat at separate counsel tables. Neither of us had an attorney.

I smoothed out my papers with my neatly typed up defense arguing that I didn’t receive a chalk mark on my tire and therefore didn’t deserve the ticket.

But I found out quickly my argument didn’t matter.

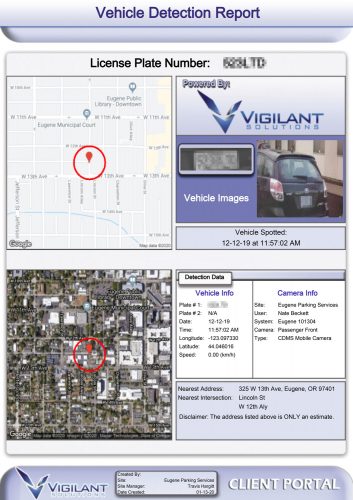

When the judge called for evidence, Becket pulled out a sheet of paper — proof of my violation — that featured a picture of my car’s license plate, including a time stamp and latitude and longitude of where the car was parked at the time. There wasn’t any way I could prove that I was within the two-hour time limit of the zone.

The ticket I received aligns with a citywide upgrade in parking enforcement technology. This shift in the system doesn’t change the parking ordinances, but enforces them differently by eliminating chalk marks on tires and making the process entirely digital. The technology upgrades will also digitize parking permits.

I wasn’t aware of the changes, and I’m not sure other people are, either.

The City of Eugene Parking Services has considered upgrading the technology for parking and checking cars since Matthew Knight Arena was built in 2010, Parking Services Manager Jeff Petry says. The city began using a digital system for cars around the arena during events.

The change solves an issue from an April 2019 Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling in Michigan that chalking cars violated the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable searches.

“How do we modernize parking technology?” Petry says. “We’ve been gradually looking for a solution.”

On Jan. 13, the city officially rolled out bright green Chevy Bolts to drive around the University of Oregon campus and the urban core of downtown, digitally marking cars.

This means the three-wheeled gas-powered vehicles will no longer patrol the streets, and enforcers will no longer stick their arms out the window to chalk car tires. These former parking vehicles, though small, cost the city more than $30,000 a car.

“They are also very expensive to maintain. They spend a lot of time in the shop,” Petry says.

The new cars, he says, are improvements for several reasons. They are electric, which was an important environmental component the city wanted. The new vehicles are also safer for the parking enforcer driving them and ultimately cost less at around $28,000. Since they are electric, the cost for running them is very low.

“By doing that it opens up a path for less expensive operations, and provides more worker safety,” Petry says.

Under the new digital system, a car is “chalked” by recording a photo of the rear license plate, the GPS location pinpointing the latitude and longitude and a time stamp. The GPS marker has a range of about 3.5 meters, Petry says, about the length of a small car.

When the parking enforcer drives by a car that is exceeding the time limit, the system pings the driver, who then issues a ticket. During this process, parking enforcers also check the location of the valve stem on the tire and the shadows on the car to see if it is in the same position as when it was first parked.

The system also has rules on personal information that is kept. Petry says they only keep the data for 30 days before purging it. If someone ends up with a citation, the data may take two years to disappear, as per Oregon state law, in case someone takes the ticket to court.

As of now, Petry says, the city does not have plans to send a press release to inform the public about the matter.

“All of this has been in line with what we have been communicating to our customers,” he says.

I couldn’t get out of my ticket. The judge kindly reduced my amount and explained the system had changed with what he described as “science fiction technology.”