In the days of COVID-19, UBI, or universal basic income, is having a moment.

Tech mogul Andrew Yang made his UBI plan, called The Freedom Dividend, a central plank of his now-ended 2020 presidential aspirations. Since abandoning his presidential bid, Yang launched Humanity Forward, a new nonprofit to help keep his UBI vision alive, among other initiatives.

With the economic impact of the coronavirus now predicted to range from catastrophic to cataclysmic, UBI-like initiatives are popping up from the House of Representatives, Sen. Bernie Sanders and even President Donald Trump.

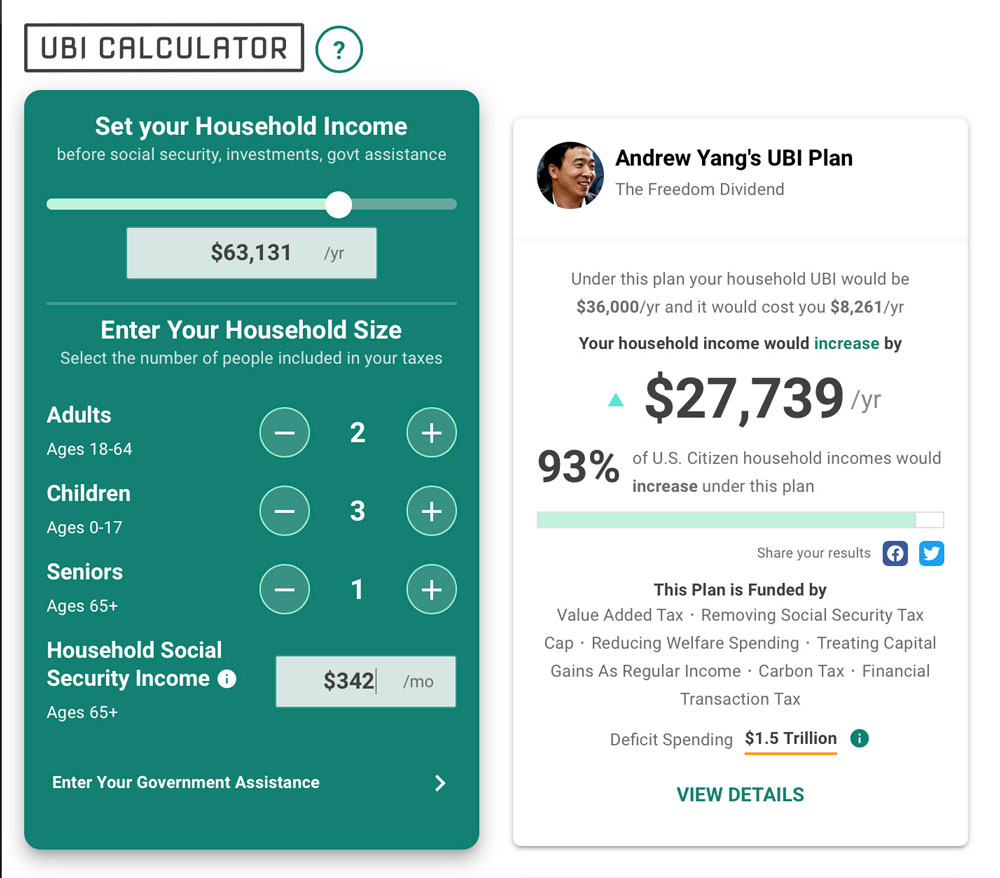

When the time comes for real legislation on UBI, voters could compare and contrast proposals with a new free web app called the UBI Calculator, developed, in part, by Eugene tech firm Twenty Ideas.

Economic and political issues are nothing new for Twenty Ideas CEO Mike Biglan. Before his career in tech, Biglan studied economics at the University of Chicago. He also served on the city of Eugene budget committee from 2005 to 2008.

“I’m an experimentalist,” he says. “We need to be trying lots of different things,” and UBI should be taken seriously, he says.

UBI is really just a new name for an old idea. In the 1960s, Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign included a UBI-like proposal, and Mike Kuhn, assistant professor of economics at the University of Oregon, points to the “negative income tax” plans of the 1970s as another early example of the concept. Under a negative income tax plan, a progressive tax code would feature positive rates for high earners but then extend to the negative domain for low earners.

Don’t bring in enough income? The government would cut you a check instead of the other way around. And believe it or not, this idea was supported by many Republican politicians of the era. With most modern UBI plans — and there are many — the government would give lump sums of money to every citizen, regardless of need, and often at the expense of other social welfare funding. Instead of targeting aid to high-need individuals, the plans say, just cut a check to everyone and be done with it: clean, efficient, less bureaucratic, and in some sense, more egalitarian.

That’s the idea, anyway.

Twenty Ideas’ UBI calculator presents a clear picture of how differing UBI proposals might impact the daily life of an average citizen, controlling for size of household and annual income. It explains how each program is paid for with data provided by individual politicians and economists, while also addressing common concerns about UBI like cost, risk of inflation, the tax burden on the middle class and disincentivizing the labor force from working at all.

“There are a lot of people out there talking about their plans,” Biglan says, with different parameters and a lot of nuance. The UBI calculator puts all that together in one place, with full transparency. Yang’s Freedom Dividend is available for scrutiny on the platform, among many others.

But Prof. Kuhn cautions that fully addressing theoretical concern about UBI is difficult because there’s never been a large-scale implementation of such a program.

“The biggest concern is if individuals are going to reduce their labor supply in response to the universal basic income,” he says. Recent research suggests that’s a very legitimate theoretical concern. Empirical studies tell a different story. “There’s a response there,” Kuhn says, “but it’s not as strong as the conservative economic theory approach might tell you.”

Another common concern about UBI is inflation — or prices being driven up by the injection of “free money” into the economy. Here, too, data is lacking, Kuhn says.

What does concern Kuhn about UBI is what such a program might crowd out in terms of other forms of social welfare spending.

“In the UBI way, the effectiveness per dollar is not as high as reinvesting in some of our existing welfare programs,” he says.

Kuhn says we take programs like food stamps (aka SNAP benefits), disability and unemployment insurance for granted.

“There are a lot of real successful stories,” he says, especially when those programs are adequately funded. But that’s not very sexy, Kuhn points out. “They’re existing programs, and people want something new.”

What’s for certain, Kuhn continues, is that UBI could be an effective way to mitigate the disruptive effects of tech and trade on the job market.

“Disruption from tech, just like trade, for example, creates winners and losers,” he says. “There are a lot of consequences for not compensating those losers adequately.”

It’s important to note, here, that one-time payouts, like the $1,200 many Americans are expecting as part of the Senate’s recently passed $2.2 trillion coronavirus stimulus package, aren’t exactly a UBI. That money is more along the lines of a tax kicker, which isn’t uncommon. For payments from the government to citizens to be truly considered an exercise in UBI, they should repeat over time, Kuhn explains.

Could we see an election in the near future with presidential candidates from both Republican and Democratc parties run on their version of a UBI plan, using something like the UBI calculator as a tool to reach their constituency?

Kuhn says it’s possible.

“Today’s Republican Party is concerned with mitigating the consequences of who loses from trade, and mitigating the consequences of who loses from tech,” he says. “There are different angles that a potential populist-style Republican could take and bring a plan along with them, and certainly there are a handful of Democrats that could run on it as well,” he says.

Biglan agrees. “The interesting thing about UBI is it seems to have a very broad range of support across the aisle,” he says.

UBI gives people the liberty to make their own choices, which is appealing to a more Libertarian mindset, while on the flipside, UBI, “creates a safety net base for huge numbers of people that are just completely left out and really struggling,” Biglan says.