In 1986, or thereabouts, Jim Weaver and I walked around Waldo Lake together for an Oregon Natural Resources Council fundraiser. There, as always, Jim was walking the talk. And what better place to do it than Waldo, a prime example of the sort of wilderness values Weaver spent his 12 years in Congress resolutely, tirelessly — and ultimately successfully — helping to protect.

But that was then. Twelve years earlier, when I was living on Riverview Street in the Laurel Hill Valley on the edge of Eugene, a cluster of apartments sprang up in a wetland area on newly paved Augusta Street, the road just below me. From time to time a man of about middle age, always nattily dressed, would visit the site as the developer-owner I soon discovered him to be.

Those of us who had lived in Laurel Hill for long enough to consider it our piece of country in the city regarded the dandy and his development as a threat to the character of the neighborhood. In truth the structures appeared to be well-built and largely fit both in design and color into their surroundings.

When I learned that this man, who wore a toupee that squatted like an invasive species among the natives left on his head, was running against John Dellenback for the 4th District Congressional seat, I wondered how his potential environmental constituents might trust a real estate developer in disguise. At the time, though, I was largely apolitical, attending more to finishing my graduate studies in English than to players in a game I deemed distant and irrelevant to my interests and milieu.

But, as I explored landscapes ever farther from campus, the ivory tower morphed into a wooded hut, and Oregon’s environment became my career. That’s when I began to understand that I couldn’t take what surrounded and had become such an intimate and life-changing part of me for granted.

A town of about 53,000 when I came to Eugene had burgeoned into a city. And, as it grew, those open spaces I’d grown accustomed to a couple of miles in any direction from the city’s center were filling up with outside industry and homegrown ingenuity and spreading up the hillsides. Escaping their influence required travel further afield.

Fleeing from one scourge, however, increasingly led to another: All those wigwam burners fouling the air fed on the leftovers of industrial tree-cutting, much of it at the time old growth fir, that was opening huge gaps in the integrity of both private and public forests. How was this happening, and more germane to my awakening, who could stop it?

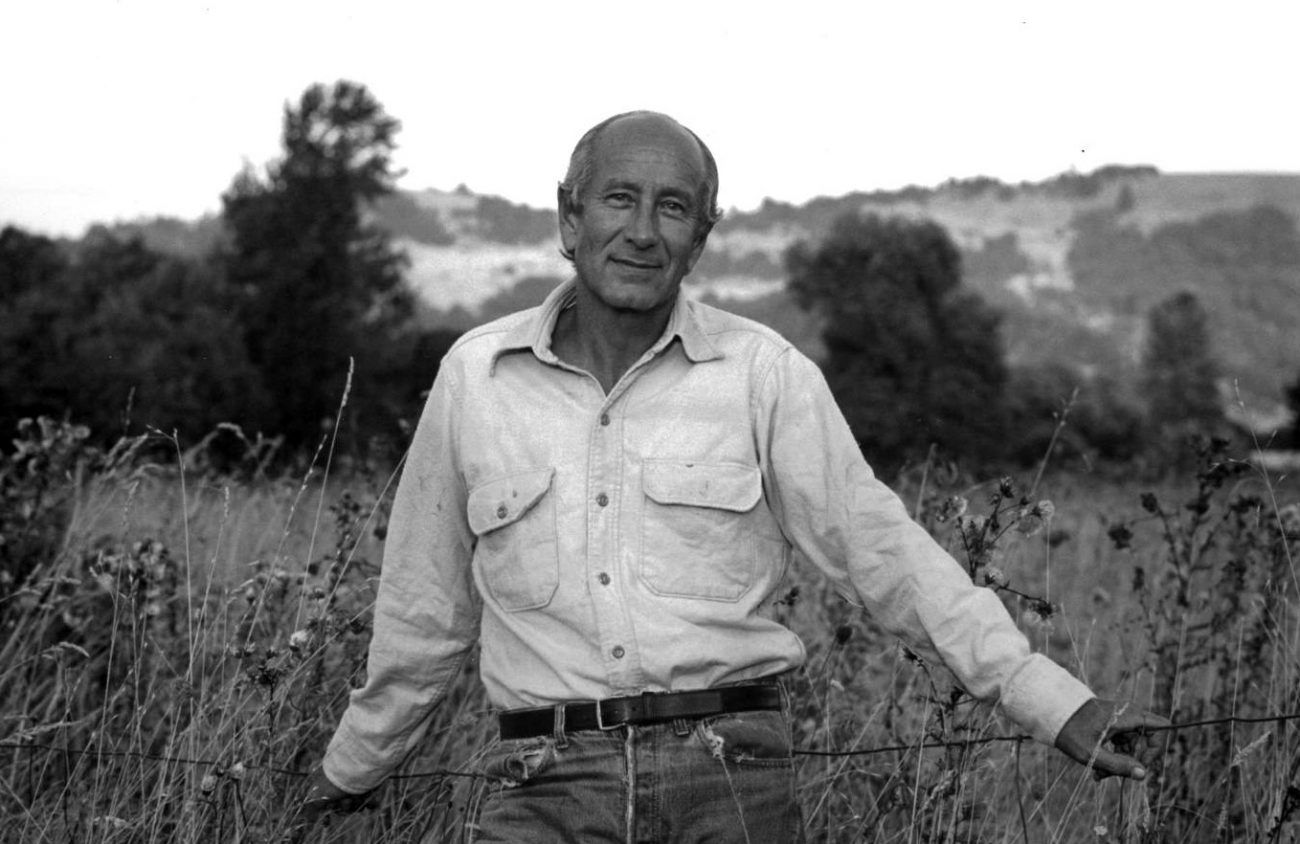

To my amazement, while I was cultivating my awareness, the dapper developer had shucked his wetland apartment complex and his ill-fitting hairpiece and was busy building a steadfast reputation for forest protection when Reagan, Watts and Hatfield were trying to turn Oregon’s wilderness and identity into stumps. Weaver’s was a tough case to make in the 4th district, much of which is dominated —still is — by the timber industry. Notwithstanding, he managed to place over one million acres of Oregon forest land under statutory wilderness preservation, save French Pete in the process and still stay in office.

That was all under his belt by the time I met Jim and we wended our way around Waldo toward a well-earned campsite and, for him, a martini and steak. What I discovered on our walk was a well-read, erudite, articulate, entertaining and largely self-educated intellectual, as familiar, I later learned, with the plots of operas from Aida to Tosca as he was with the intrigues, intricacies and inadequacies of Congress.

After he left his congressional seat in 1987 Weaver returned to Eugene, and our paths began to cross when he interested and involved himself in local issues. Issues such as the state’s and the county’s dumping of toxic wastes in a wetland near his house on Seavey Loop; in the threat to the rich farmland and natural areas nearby by development interests and other discordant activities; and in the prolonged fight by neighbors to stop the mining demolition of Parvin Butte near Dexter.

Disgusted by conservative mayor Jim Torrey’s politics and practices, Weaver ran against him in 1996 when he was 69. Increasingly, however, he was frustrated by aging and his inability to fight what he perceived as the creep of fascism in corporate-controlled America, the appointment of ultra-conservative Supreme Court and other judges, and their counterparts and consequences in his own backyard.

In 1992 Weaver published a book called Two Kinds in which he argues, with research into other cultures as well as his own, that there is a “genetic predisposition” to be either ethnocentric-conservative or empathic-liberal regardless of education or economic status. In the book’s epilogue he concludes:

“The human population has quintupled in the past one hundred years, fomented by two extraordinary events: the exploitation…of petroleum, and the advent of a most unusual and benign climate. Oil will run out soon, and the climate is likely already changing. The billions of humans who have thrived through our 100 year binge on oil and benign climate are now in jeopardy.

If we survive… it will be through our powers of reason and learning and the evolution of cooperation… We must cleave to democracy.

We are but one animal on the face of the earth. It is our task to preserve our dwelling place and those who live with us. If we do not do so, nature will do it for us.”

Until his keen mind and voice began to fail him a few years ago, Jim did what he could, when he could, while he could, to apply his powers of reason and learning to our survival in a devolving politics of cooperation. His dedication and achievement will stand forever with Morse, McCall and others who devoted themselves to the defense of Oregon’s natural environment and our place in it.

When I return to Waldo Lake, I’ll step again on what is now officially named the Jim Weaver Loop Trail, grateful for the opportunity to have shared that path with him so many years ago and for all the paths we’ve taken together since.

Robert Emmons is president of LandWatch Lane County.