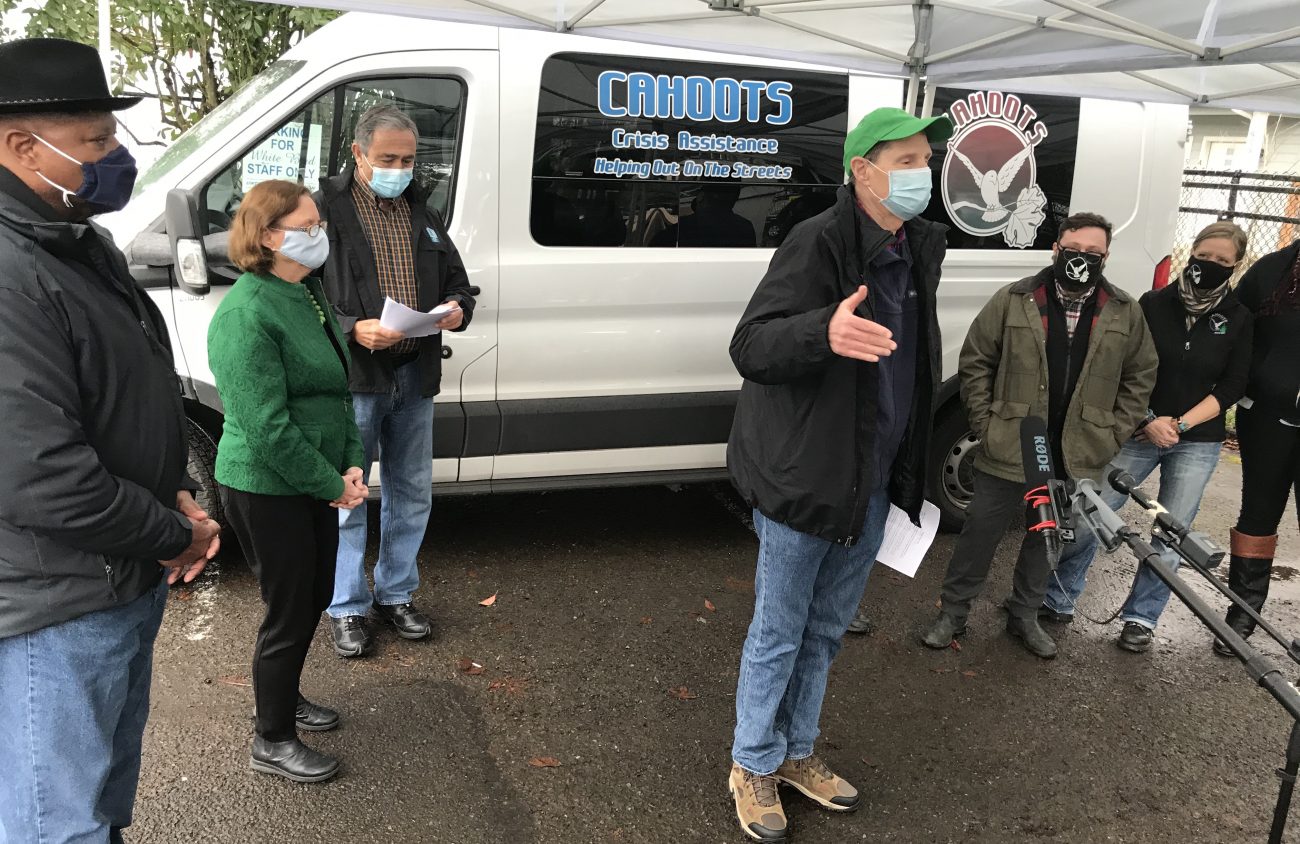

Surrounded by CAHOOTS staff and local and state politicians, Sen. Ron Wyden announced he had re-introduced a mental health bill that would increase federal money for social services like the Eugene agency around the country. For Wyden, the work that CAHOOTS does is personal.

“My brother was schizophrenic,” Wyden said at the Feb. 19 event. “In our family, night after night after night, year after year after year, we went to bed worried that my brother, Jeff, was going to hurt himself or hurt somebody else.”

Wyden’s brother’s schizophrenia, he added, is what sparked his interest in addressing the U.S.’s mental health system.

With new leadership in the White House and Congress, Wyden addressed the media, CAHOOTS and local and state leaders about the re-introduction of the bill named Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets. The bill, if passed, would use Medicaid money for CAHOOTS-like programs throughout the country. Because the bill was included in the House’s COVID-19 relief package, the bill could pass without filibuster threat from Republicans.

At the event, local politicians praised CAHOOTS and how it serves the vulnerable, but the bill is just the first step in addressing the failing mental health system.

“Under my legislation, states would get an extra boost of federal funding in Medicaid to provide these services for individuals experiencing a mental health crisis,” Wyden said. “The federal government would pay a higher percentage on the dollar for these services to be offered, with states picking up a smaller share.”

The bill, named after the White Bird program, gives states further enhanced federal Medicaid, which is intended for low-income people such as those CAHOOTS often serve. The funding is for three years to provide community-based mobile crisis services to individuals experiencing a mental health or substance use disorder. It also provides $25 million for planning grants to states and evaluations to help establish or build mobile crisis programs and evaluate them.

The bill’s co-sponsors include Sens. Jeff Merkley, Dianne Feinstein (Calif.), Bernie Sanders (Vt), Sheldon Whitehouse (R.I.), Tina Smith (Minn.) and Bob Casey (Pa.).

Wyden’s office says in an email that the bill is in the House’s $1.9 trillion Reconciliation Relief Legislation package. Earlier this month, Wyden’s staff says, the House’s Energy and Commerce Committee included a provision in its budget reconciliation language for COVID-19 relief that makes an investment in these services by funding state Medicaid programs at an enhanced 85 percent federal match if they choose to provide qualifying community-based crisis intervention services and funding state planning grants for the option.

Because Democrats were unable to secure party support in the Senate to get rid of the filibuster, the majority may have to use a budget reconciliation vote to pass the package that the bill is in. It’s a process that allows the Senate to pass legislation with a simple majority and avoid the two-thirds needed to end debate (which is where the filibuster comes into play).

Wyden says he expects to get the legislation sent to President Joe Biden’s desk through a reconciliation vote. “If you can draw a strong nexus to budgets and spending, which we do with the larger federal share for these Medicaid services, you can avoid what’s called the Byrd Bath,” he said. “We think we can get around all that by the focus on the spending and not get disqualified.”

Wyden first introduced the bill in 2020 when CAHOOTS caught national attention after the killing of George Floyd sparked outrage on policing. The bill would use Medicaid, which Wyden said is the largest funder of mental health services, to support CAHOOTS-like programs throughout the U.S. But the bill never left the committee under a Republican-led Senate. Wyden said it was a fight to maintain Medicaid funding during the Trump administration. With the Democrats in the majority, now Congress can push for increased funding.

CAHOOTS program coordinator Ebony Morgan said that during the pandemic, White Bird was struggling and had to reduce some of their services even though there was higher demand. “We had a lot of people working too many hours, and we had to do what we could do to protect ourselves,” she said. “The need went up as our capacity didn’t. That was difficult for our team to navigate because we all care so much. We don’t do this job for any reason besides we care about the community.”

She added that the nonprofit is exploring ways to meet the needs of the community.

In addition to CAHOOTS staff, the event was attended by Eugene Mayor Lucy Vinis, state Sen. James Manning and Lane County Chair Joe Berney.

Vinis referenced the city’s ad hoc committee on police policies that was created in response to 2020’s protests of George Floyd that happened in Eugene. “The key message of that ad hoc committee was de-escalation,” she said. “How do you work with someone who is in a mental health crisis?” Vinis recalled testimony from a resident who said Eugene needs to embrace the mentally ill. “You know that is true for Eugene; we know that it is true for the entire nation,” she added.

Although the country has frequently said they’re in it together over the pandemic, she said that “we have not been in this together. We have marginalized people who struggle with mental health, we have treated them as criminals.” CAHOOTS, Vinis said, works with those going through mental health issues, taking it off the shoulders of the police, “who aren’t prepared to do that work.”

Manning, who serves as the Oregon Senate president pro tempore, said there’s no need to conduct a study on the efficacy of CAHOOTS — because Eugene has 30 years of experience with the program. “My job is to also see if I can implement this program statewide. Sen. Wyden is working on it at a federal level so we can get this thing nationwide.”

Manning added that CAHOOTS workers not only save tax dollars but also lives. “So I’m looking forward to continuing the work I do to provide funding,” he said.

Lane County Commission Chair Joe Berney painted the county as another area affected by a broken mental health system. Many in need of resources have nowhere to go, he said; the Eugene Mission is on lockdown due to COVID-19, The Buckley Center puts people on the streets too soon, the county offers tents and sleeping bags, but police homeless sweeps are still happening.

“Understanding the grim reality, we also understand the potential of which your legislation could unleash,” Berney said. “Let us use this legislation not to say that we’re done, but to begin as a wedge to start fixing broken systems in disrepair on behalf of the most vulnerable among us.”

But for Wyden, the bill remains not just as a way to spread the CAHOOTS model throughout the U.S. and address the country’s mental health system, but he says he’s doing it for his parents, too. “This is really special. This is in the heart of my parents. This is something that my parents would want me to be part of for my brother.”