By Andrew Heben

As someone with a background in urban planning and a general interest in creating a more livable Eugene with a diversity of housing options, I am a strong supporter of the residential zoning changes proposed under the Middle Housing Code Amendments.

By adopting the state mandated changes to allow up to four dwellings on most residential lots in Eugene, this will give us a tool to recreate the denser neighborhoods we so desperately need. Cities continuously change; as people we can either adapt or move. Those who oppose increased density as a means to accommodate the growing amount of people moving to Eugene may be better suited living outside of the urban growth boundary.

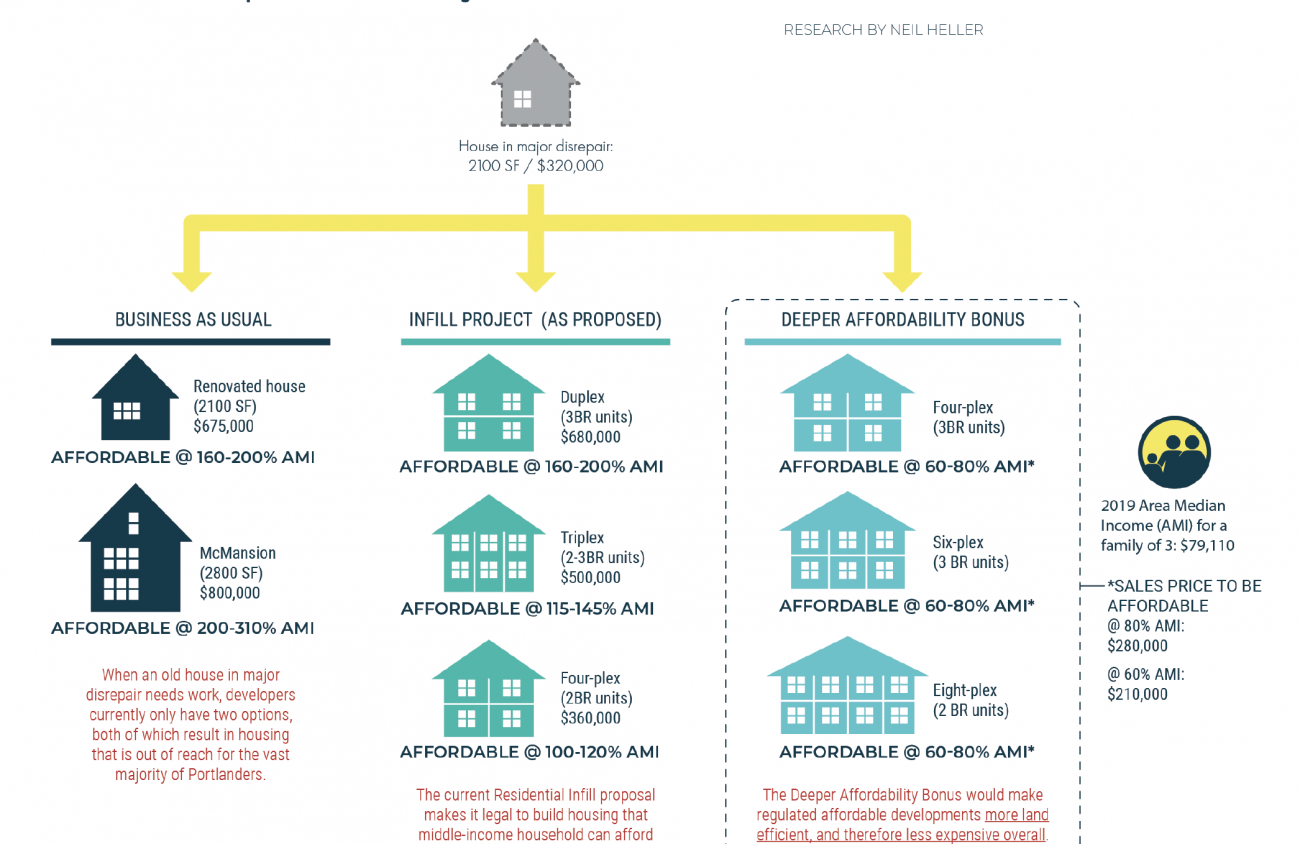

But as the project director at SquareOne Villages, a developer of permanently affordable housing co-ops in Lane County, I think we must do more. The draft code as proposed would not have much benefit to SquareOne’s mission of creating quality housing for people earning under 80 percent of the area median income (around $40,000 per year or less) unless the city adds a “deeper affordability” option.

In essence, a deeper affordability option could allow up to eight dwellings that are affordable to people with low incomes (i.e. 80 percent area median income or below for homeownership and 60 percent area median income or below for rental housing) on properties that would otherwise allow four market-rate units under the middle housing code.

This is not a new idea. Eugene’s existing land use code already allows a 150 percent density bonus for low-income housing developed in residential zones. And the recent enactment of Oregon Senate Bill 8 now supersedes that, providing a 200 percent density bonus for low-income housing developed on R-1 land. We cannot afford to miss the opportunity to extend a similar density bonus within the Middle Housing Code Amendments.

The C Street Co-op pilot project in Springfield, which was recently completed through a partnership between SquareOne Villages and Cultivate, provides a strong example of what is possible in our community if a deeper affordability option is included.

The innovative infill project provided a pathway to permanently affordable, owner-occupied housing for six individuals and families, with monthly housing costs around $780 per month, affordable to someone earning just 60 percent area median income. And because the housing is cooperatively owned by the residents, those costs will only get more affordable over time.

To my knowledge, no other housing in Lane County is providing a more accessible pathway to homeownership, and it also exemplifies the most cost-effective use of public subsidies that I am aware of.

Total development costs were approximately $600,000, or $100,000 per one-bedroom suite. Project financing included foundation grants (10 percent), CDBG down payment assistance (10 percent), resident equity (10 percent), a mortgage from Summit Bank (65 percent) and a small loan from social investors to fill the gap (5 percent).

That comes to approximately $20,000 in subsidy per one-bedroom suite, which is a radically more cost-effective model than low-income rental housing financed with federal low income housing tax credits (LIHTC), which currently require upward of $250,000 in subsidy per unit in order to achieve similar affordability levels for renters.

If we as a city are going to say with a straight face that we are working our hardest to address the affordable housing problem, then we must look beyond the limited supply of federal tax credit funded projects, and develop local funding and policy solutions that also incentivize other types of affordable housing, such as limited-equity co-ops.

We currently have the opportunity to subsidize housing not by spending money, but by allowing affordable housing developers like SquareOne to spread costs across more units in the interest of increasing affordability. Without doing so, new middle housing developments for people earning below 80 percent AMI simply won’t pencil out, and are therefore unlikely to be built.

The city has stated that affordability and equity are the primary goals of these code amendments. Throughout the participatory process there have been a number of voices calling for a deeper affordability option to better meet these goals. And the central argument of most opponents is that the middle housing zoning changes will increase wealth inequality and put housing further out of reach for people with low-incomes.

A deeper affordability option offers a tangible response to that feedback, by giving affordable housing developers a much needed edge over market-rate developers in this hyper-financialized housing market we find ourselves in.

At SquareOne Villages, we are eager to replicate the C Street Co-op pilot project at a meaningful scale in Eugene. Multiple landowners have already approached us with an interest in donating a single-family property, or selling it to us at a reduced rate. But we first need the city to step up and allow us to do more through the inclusion of a deeper affordability option within the Middle Housing Code Amendments.

Andrew Heben is a resident of Eugene, co-founder and project director at SquareOne Villages, and author of Tent City Urbanism: From Self-Organized Camps to Tiny House Villages.