“The world is an unpredictable place where bad things happen,” medievalist Martha Bayless says. Going into year three of the COVID-19 pandemic, I’m with her so far. “Things seem to happen randomly,” she adds. “People use magical thinking to get some control over their lives.”

The concept of magical thinking frames Magic in Medieval Europe, an exhibit on view through August at the Museum of Natural and Cultural History at the University of Oregon, where Bayless is professor of English and director of the Folklore and Public Culture Program. She is curator of the exhibit and also author of numerous books on topics related to medieval popular culture, such as Parody in the Middle Ages and the forthcoming Cultural History of Myth in the Medieval West.

When studying history, traditional approaches are to compare or contrast. Bayless says she likes to compare: Her focus is on how we are similar to those who lived before, not how we’re different.

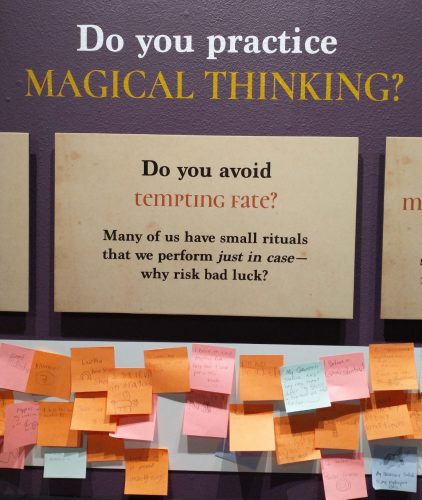

Moving through the exhibit, I can see the focus on commonality. “Do you practice magical thinking?” asks one interactive presentation. In response are a host of sticky notes with examples given by visitors to the museum. “I believe in dragons,” reads one note apparently written by a child. On the note also is a tiny drawing of a large beast with small wings.

Ann Craig, director of exhibitions and public programs at the museum, responds to the question, too. Growing up, she says, her family members threw spilled salt over their shoulders to avoid bad luck. She kept up the practice and says that her 12-year-old daughter “recently admitted to purposely spilling the salt when she was little just so she could throw it over her shoulder.”

Magical thinking and associated spells, objects and behavior often relate to avoiding bad luck, or getting rid of it once it occurs. Getting ill is a sort of bad luck, and illness was treated with various types of practices associated with magical thinking. For example, a walnut looks similar to a human brain, and using a walnut to treat diseases of the head or brain reflects the practice where people think similar looking things can influence each other.

In other words, like goes with like: one thing “influences” the other. This type of thought was common in the Middle Ages in Europe during the plague, but has existed in many cultures and persists even today.

In spring 2020 President Donald Trump suggested scientists look into injecting disinfectants to fight the virus. If bleach and other disinfectants clean one thing, then why not the other? Some see this moment as a symbol of how the country got off track fighting COVID-19. The medical community reacted by telling people not to drink bleach, but there was still a reported uptick in accidental poisonings after the president’s comments.

Disinfectants clean things, so why not use them to remove the virus? After visiting the exhibit on medieval culture, it seems clear that Trump was engaging in magical thinking when he suggested we use household disinfectants for eradicating the COVID-19 virus.

To be clear, Trump or current politics are not mentioned in this show. But if the museum’s goal is to encourage seeing similarities, it’s totally working. And it’s hard not to think about the current pandemic, especially when looking at the display on the bubonic plague.

The plague display is not a prominent or central feature of the exhibit. But there is no moment in the show when I’m not aware that we’re in the middle of a health crisis. As I’m trying to keep my distance from other visitors and wearing a mask that fogs my glasses so it’s hard to see, the display on using toads to cure the Black Death strikes a chord.

An illustration from the 15th century depicts toads with and without the swellings that were symptomatic of the plague. “Why toads?” asks the display — and then answers with this bit of magical thinking: “Toads are often poisonous and have bumpy skin, too. See the similarity?”

Magic in Medieval Europe reminds us that not only are we similar to those who lived centuries before, we are also direct descendants of their traditions. Leaving cookies out for an intruder wearing a beard and pointy cap on Dec. 24, for instance, can be traced to having house sprites.

What is a house sprite and how do you know if you have one?

Well, they stay just out of sight, I learned, so they can’t be seen. But if you’re experiencing some mischief or things going wrong at home that can’t be explained, try leaving out some sweets. If those are taken, then the bad luck at your house might just disappear as well knock on wood.

Magic in Medieval Europe runs through August at the Museum of Natural and Cultural History, 1680 E. 15th Avenue. Hours are 10 am to 5 pm Wednesday-Sunday, open until 8 pm Thursday. Admission $6 adults, $4 youth and seniors. Masks required.