Two of the three founders of the Eugene-based Emano Metrics met as graduate students at the University of Oregon’s Department of Physics, but were interested in something other than academic research.

“We wanted to start a business,” Bishara Korkor says about co-founder Teddy Hay and himself. “We were always throwing business ideas at each other.”

One of the ideas that stuck came from Hay’s father, Alan Hay, who’s the third co-founder of the company and a Salem-based urologist. Alan Hay asked Teddy if he thought a smartphone’s microphone could be used to measure someone’s urine flow rate, a measure of prostate health, just by sound.

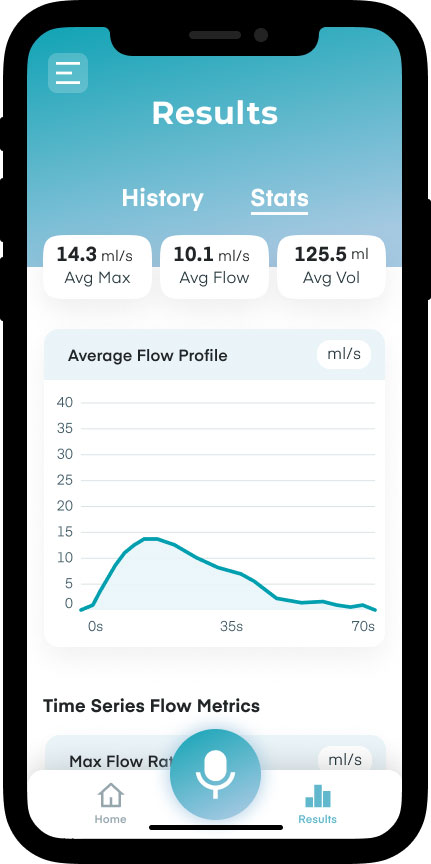

About three years — and one patent — later, Emano Metrics’ program Emano Flow can quantify urine flow rate and help physicians understand their patients’ urinary issues with just a smartphone microphone, Korkor says.

The technology, he adds, minimizes the amount of time patients have to spend journaling about their bathroom trips.

“There’s a smartphone in everybody’s pocket, even if you look at the older population that has the particular urological issues,” Korkor says. “They’ve got smartphones and know well enough how to use them to hit the record button in an application.”

Health issues related to prostates are common with older men and people assigned male at birth as they age. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 13 out of 100 American men will develop prostate cancer, and it’s the second cause of death in the U.S., behind heart disease.

There are a few ways to monitor prostate health, Korkor says. To see how the small gland between the penis and bladder, called the prostate, is impeding urination, he says patients have a few options. One is a single urine test and the other is a diary.

The problem with the current urology standard of measurement of a single flow test, he says, is that it doesn’t provide an accurate picture of how a prostate impacts flow. “Single sample tests are notoriously problematic for anything that is sampled from a large distribution,” Korkor says, referring to the number of times people use the bathroom in a day. “The maximum flow rate by an individual is totally variable across their urinations.”

He adds that if a patient’s maximum flow rate is 20 milliliters per second, “it is quite common in some urinations to have it as low as 10 and others as high as 30.”

Patients may also have to fill out a bladder diary, writing down how much they drink and estimate how much they pee and how often they go. “It’s really tough to get patients to fill it out,” he says. But, Korkor adds, the nearly 100 patients who have used Emano Flow so far have shown higher rates of compliance, and that’s provided physicians with an objective view of a patient’s urine flow, Korkor says.

Emano Flow is meant to allow patients to measure their urine flow, which could reduce clinic staff and office costs related to the test. Since patients can measure their urine flow at home over several days, it provides physicians with an accurate estimate of the average maximum flow rate, Korkor says.

When the product is finished, the patient will record their urine flow with their smartphone and the audio recording will be sent to Emano Metrics’ server, which will analyze the data. The measurement is sent to the urologist.

Emano Metrics is trying to start a clinical trial with Oregon Health and Science University, which Korkor says would be an accuracy study as a way to keep up with the company’s competitors who have similar technology. Thus far he says the company has heard positive feedback from early users.

He says Emano Metrics heard from a physician who was able to use data from a patient using Emano Flow to discern between different urinary conditions. The patient was complaining about waking up at night to urinate, he says, referring to testimony submitted by a physician enrolled in the program. It was a scenario that a physician without the urinary flow data may have hypothesized the patient had benign prostatic hyperplasia (also known as an enlarged prostate).

“The guy was just taking a drug that was causing him to urinate at night, and once he stopped taking the drug, he stopped having the problem,” Korkor says. “Now he’s minus one drug instead of plus one drug.”

For more information, visit EmanoMetrics.com.