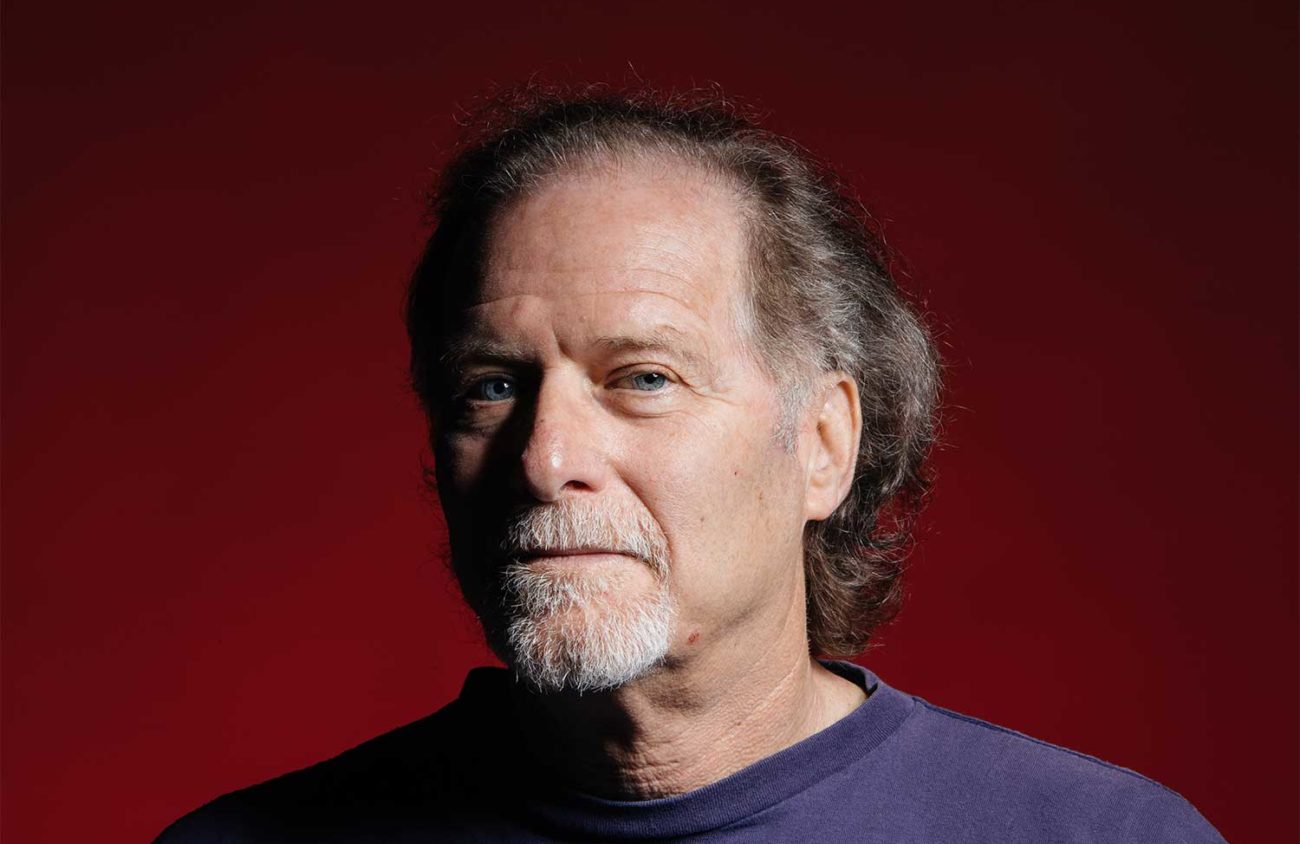

David and Goliath is one of the most told underdog stories in history, an allegory used to describe most uneven fights from sports games to grassroots politics. And it’s how former University of Oregon Labor Education and Research Center director and former organizer Bob Bussel looks at organized labor struggles, from the 1970s labor movement to today.

Reflecting on his previous union work, which spans his start at organizing boycotts for United Farm Workers (UFW) and the union that represented workers at the East Coast J.P. Stevens textile company to leading the UO’s labor program that educates students and provides reports on labor, Bussel says the union movement has always been a drawn-out battle between workers and companies. That’s how it was when UFW organized for better working conditions, he says, and what it’ll be like for today’s nascent unions — that are more inclusive than yesterday’s organized labor — that take on large corporations.

“I look at the labor movement as the boxer who wins over 10 rounds. We don’t usually have a knock-out punch. We have to win on points and hit them in a lot of different areas,” he says. “That’s what I learned from UFW and J.P. Stevens. We had multiple strategic tools and weapons to pressure our opponents.”

When Bussel had his baptism into the labor movement, as he calls it, he joined the UFW as a volunteer while the union was in the midst of its 1973 grape boycott. The union, which was formed in the early ’60s, was trying to negotiate a new three-year contract with California growers, who had instead opted to work with workers under the Teamsters union. The UFW argued in a 1973 leaflet that was distributed to consumers and archived by University of California, San Diego, that the Teamsters’ workers contract didn’t have farmworkers’ best interests, as it offered workers 10 cents less per hour, as well as no language on child labor, overtime pay or job safety.

“We would go out every Saturday, rain or shine, in front of grocery stores and have picket lines but also talk to consumers,” Bussel says. “That’s where I really learned my organizing ABCs.” Grocery store managers would see some customers turn away, not wanting to cross the picket line. They weren’t just seeing losses in produce, he says, but other store sales, too.

In 1975, the UFW boycott, led by César Chávez, ended when California Gov. Jerry Brown signed the Agricultural Labor Relations Act into law. The law gave farm workers the right to form unions or join others, giving them bargaining rights with farmowners.

Organized labor battles don’t end quickly and sometimes take several years to resolve. These conflicts favor the employer, as it can draw the process out through the courts, he says.

In 1983, Bussel recalls working on a campaign to unionize workers at Columbia Textile Factory in New Jersey. The company interfered with the union elections, including spying, threatening to close the factory and firing key members of the labor union’s bargaining team.

The U.S.’s labor law enforcer, the National Labor Relations Board, criticized Columbia, but Bussel says it took years for legal consequences for Columbia to happen. The NLRB ruled Columbia had violated federal labor law. It took seven years of court appeals by the textile company, he says, which came to an end in 1990 when the District of Columbia Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the workers and ordered backpay.

Bussel says he stopped working as an organizer during the Reagan administration. In 1981, President Ronald Reagan fired 11,345 workers with the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization who were on what was decided to be an illegal strike; that led to the disbanding of the union. It was a bleak time for unions, Bussel says. “We won some, but the NLRB process was really difficult in the private sector textile industry on the East Coast,” he says.

After organizing, Bussel went back to school, finished grad school and worked in labor education. In 2002, he joined the UO’s Labor Education and Research Center as its director. For nearly 20 years, he says he wrote reports on the state of labor, penned two books and taught the future generations of labor activists.

On Dec. 15, 2021, he retired from LERC, leaving as unionizing entered its current state of mainstream approval. As workers throughout the U.S. attempt to unionize workplaces at Starbucks and one Amazon warehouse — even other areas from health care to weed dispensaries — public polls show support for the labor movement. According to a Sept. 3, 2021, Pew Research poll, 55 percent of Americans say labor unions have a positive effect on how the country is doing.

“It’s been true throughout labor history that external events really drive big periods of labor growth,” Bussel says. “For example, I often joke that it was world wars that drove a lot of union growth — I don’t recommend world wars.”

In recent years, COVID is that external factor, he says. “The sheet rock is down and the wiring is exposed. We can see structural problems,” he says. “We knew that a lot of work was essential, but it took COVID for society to see that farmworker is important, that grocery worker is important, that nurse is important, that transit worker is important.”

Unions have a changing demographic, too, he adds. Unions are more inclusive than yesterday’s with more women, people of color and younger people. “It’s not your grandfather’s union anymore,” he says.

Looking at the future of unions, Bussel thinks back to his body surfing days. Sometimes you think you see a wave far into the horizon but it peters out by the time it gets to you. But in this case, he sees a real wave on the way. “This is a real moment, and we don’t know exactly where this will lead or what it will come to,” he says. “But it’s incumbent on the official union movement to try and seize this wave.”

But can David beat today’s Goliath?

Yes, Bussel says, but it’ll take more than just a slingshot. The NLRB would have to be aggressive in enforcing the law, which it has been under the Biden administration. More established labor groups will have to work together with workers forming new unions. And the public will need to be supportive of the cause. With all of that occurring, he adds, he sees an outcome where even the wealthiest union busting corporations will allow unionizing in the workplace.

“There’s this readiness of workers that COVID has brought out. I think there are more politically aware younger people who have been politicized or radicalized by the Great Recession, COVID, their own prospects of the world, concerns that capitalism isn’t working,” Bussel says. “It’s pretty damned exciting.”

This story is a part of Eugene Weekly’s reporting series on the labor movement in Oregon, funded by the Wayne L. Morse Center for Law and Politics.