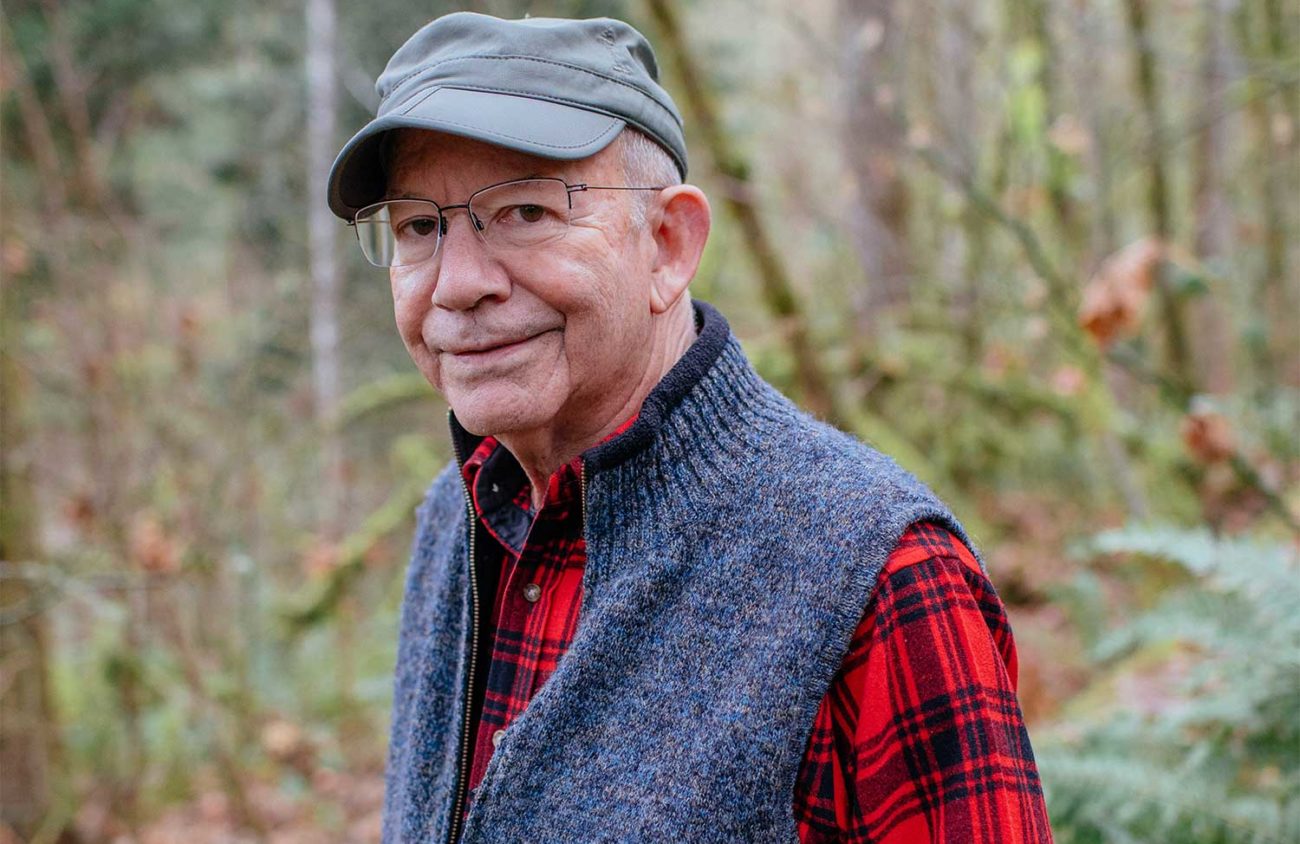

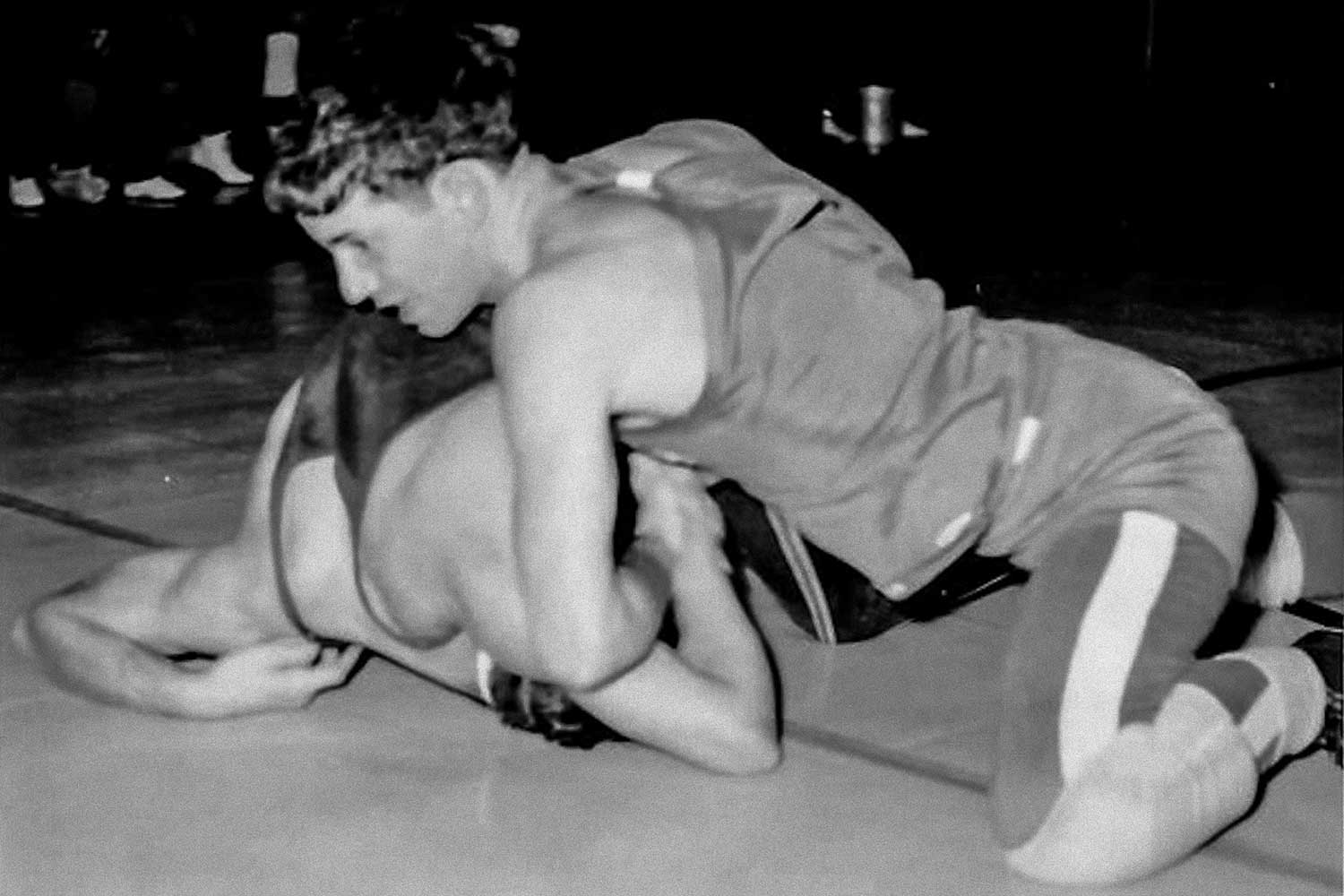

Wrestling is in Congressman Peter DeFazio’s blood. He grew up in the sport, and his father is enshrined in its hall of fame. And wrestling, which has been around longer than democracy, taught him how to work in the U.S. Capitol.

“I think wrestling prepared me for politics. In wrestling, it’s one-on-one out in front of everybody — you can’t blame a teammate,” DeFazio tells Eugene Weekly.

DeFazio never earned the fame as a wrestler that his father earned as a coach, as he quit the sport while in college, but he’s taken note on how to leave on top from his father’s 32-year coaching career. Mike DeFazio, who was inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame in 2002, coached Needham High School in Massachusetts, winning the Massachusetts State Wrestling Championship in 1965 and in 1966. In that latter year his team was undefeated, according to his hall of fame listing. He retired in 1966.

Enlarge

“It’s like when my dad retired after he won the New England wrestling tournament,” DeFazio says. “I feel like it’s a good time to go — I’m on top.”

Undefeated seasons are rare in politics, but DeFazio tells EW that he’s retired with the congressional equivalent of his father’s two state high school wrestling championships. In recent years, he’s worked to save the U.S. Postal Service retirement program, he’s passed a massive transportation bill and he’s taken away the antitrust clause that allows health insurances to price gouge. And he’s served as the powerful chair of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee for his final two terms.

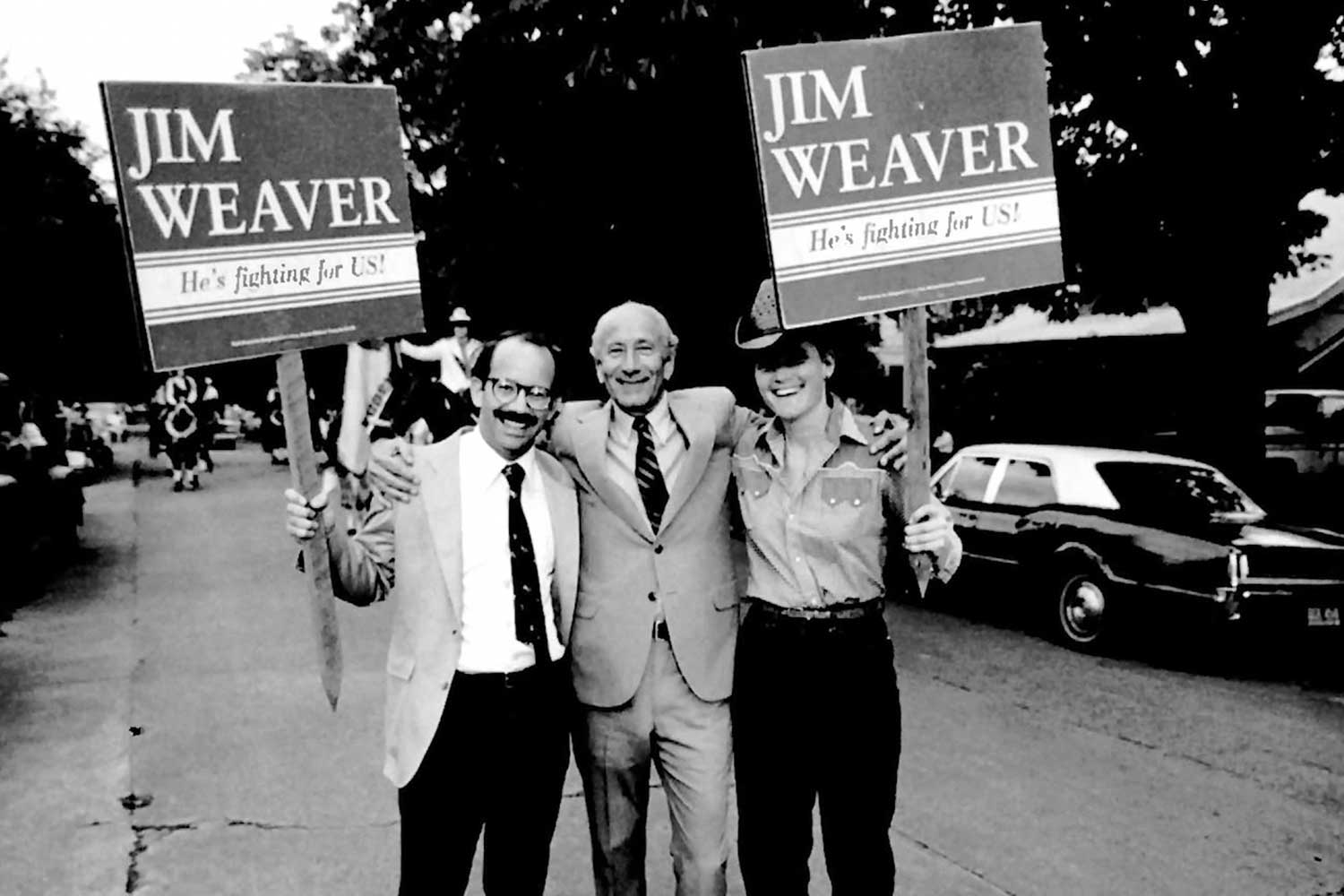

With a progressive ideology that germinated as a kid working for his father, DeFazio’s political career began shortly after moving to Oregon in the 1970s — after getting his BA at Tufts and a stint in the Air Force Reserves. While working as an aide for then-Congressman Jim Weaver, DeFazio was launched into politics with a lawsuit against a regional nuclear power plant plan that resulted in what he says is a financial fallout eclipsed by the savings and loan crisis in 1989.

Once elected to Congress in 1986, DeFazio represented the whole state, gaining respect from his peers for pushing for progressive policies and protecting the environment while not isolating the working class.

DeFazio leaves behind a congressional seat that he held for 18 terms — 36 years — to his hand-picked successor, Rep. Val Hoyle, and he will no longer have to commute from Oregon to Washington, D.C., every week.

Ready to Rumble

Decades before becoming a congressman, the summers of DeFazio’s youth were spent at the Eastward Ho! Golf Course in Cape Cod. Working as a caddie, it’s where he was introduced to wealth inequality, an issue that helped define his career in Congress. “Entitled wealth is really perverting the system,” DeFazio says.

From 1952 to 1969, his father ran a caddie camp for inner-city children, DeFazio says. “He was known to deal with troubled kids,” he says of his father. “A lot of kids would get sent there instead of reform school.”

At the caddie camp, DeFazio worked at the golf course, parking cars and carrying golf clubs for rich people. But he related more to the inner-city children at the camp, he says. “I developed an attitude about entitled wealth, which has carried over into my politics,” he says. “It started being there, thinking ‘These people aren’t special. They’ve just got a lot of money.’”

Those childhood memories of wealth disparity at a New England country club were the origins of a congressman who would decades later relentlessly demand taxes on Wall Street and the wealthy. But first DeFazio would find himself as an “unintentional politician,” learning about constituent services as a congressional aide for Weaver, a function of political office he would prioritize when he became a congressman himself.

His foray into politics started while he was in graduate school at the University of Oregon.

DeFazio was studying gerontology at the UO when he learned that Weaver was looking for an aide in Oregon. DeFazio was hired, joining the Eugene district office with another soon-to-become pillar of Eugene: Cynthia Wooten.

Wooten’s legacy includes the creation of many beloved institutions that have given the city its identity. Among her long list of accomplishments, she helped found Eugene Celebration and the Oregon Country Fair. And that doesn’t include her roles in politics, including Eugene city councilor, Lane Education Service District board member and the Oregon legislator.

Before Wooten and DeFazio launched their own political careers, they worked together in Weaver’s Eugene office. DeFazio and Wooten were a part of the district staff who would assist constituents with their questions and needs, Wooten says. At the Eugene district office, Weaver’s staff assisted constituents with accessing Medicare, Social Security, immigration, veteran pensions and other services.

Enlarge

“He was devoted to casework on a constituent basis,” she says of DeFazio. “His work wasn’t developing legislation or doing any major policy work, but it was clear that Peter came to Eugene, finished his master’s degree and had an agenda for himself.”

That goal was to become a congressman, Wooten says. “That’s admirable in a way that you know what your path is going to be and you chip away getting there, step by step.”

Constituency work was a duty that DeFazio would carry on during his time in Congress, making it one aspect of the office that he may be best remembered for.

“I would say the gold gem in his career is his passion for case work,” says Karmen Fore, who was his campaign manager in 1994, his district director from 2003 to 2011 and his deputy chief of staff from 2011 to 2013. “Our goal in that office was to be the best at constituent services, bar none.”

As a congressman, DeFazio used constituent service as the metric for how successful someone was in his office, Fore says. She says the office maintained detailed reports that cataloged case work by staffers.

DeFazio would get upset when constituents would call about being stuck in bureaucracy trying to access services, whether Social Security checks or veteran benefits, says Fore, who is now Hoyle’s chief of staff. Sometimes, DeFazio would even accompany constituents to the Social Security office, she adds, standing at the counter with them until they were served, she says. “That kind of passion for your staff and constituents is a big deal.”

In 1977, DeFazio finished his master’s degree, researching the Social Security disability determination process, and was shocked about the system. “I said, ‘This is broken, and it’s broken from Washington in terms of the policy,’” DeFazio says. He then moved to work in Weaver’s D.C. office.

While at the nation’s Capitol, DeFazio says he saw how lifeless many of the politicians there were. And that’s what inspired him to become a politician himself, he says.

“I’d sit in a hearing or watch the floor and I’d see these people reading from their notecards,” he says, mimicking the politicians’ monotone. “And then there would be an obvious question to ask that someone had just testified to but that wasn’t on their list. A lot of these people were just pathetic.”

Enlarge

Politics, Slime and D.C.

Back in Oregon, DeFazio found himself getting involved with a lawsuit against Springfield Utility Board, a case that would propel him into politics.

“We were like the Lilliputians versus the giant,” DeFazio says.

The 1981 lawsuit against SUB was regarding its contract with the Washington Public Power Supply System (WPPSS, aka “Whoops”) along with 88 government agencies. The agreement was to raise funds to construct and operate five public nuclear power plants, called the Washington Nuclear Project. WPPSS was behind schedule in building the two power plants that Springfield — among many other cities — would buy energy from. The cost estimates ballooned to $9.3 billion, five times more than initial estimates, according to a 1991 article in Columbia, a magazine covering Northwest history.

DeFazio was one of many community members who showed up to SUB meetings to pressure the agency to withdraw from the agreement. Whether SUB stayed in the contract with WPPSS or exited, it would mean higher bills for ratepayers to repay its bonds, according to Columbia.

“I led the first protest march that anybody knows of in Springfield. We circled the utility office and burned our utility bills,” DeFazio remembers.

The idea to burn the bills came from Wooten, DeFazio says, while they were drinking beers one night. “Next thing I know, I get a call from KUGN in the morning saying, ‘We understand that you’re leading a march on the Springfield Utility Board and you’re gonna burn your bills,” he recalls. He laughs, remembering the call, saying that Wooten had called the news station with the tip.

The group brought their candles inside the new Springfield City Hall, sparking the building’s sprinkler system and spreading wax all over its floors, DeFazio says. “I had to come in the next day and scrape it up. That started my political career.”

With the legal help from Eugene attorney and social justice advocate Robert Ackerman, DeFazio represented community opposition as the plaintiff of a lawsuit against SUB. Citing the Springfield City Charter, the case argued that SUB overstepped its powers by entering into agreement with WPPSS, as purchasing bonds requires approval from voters, according to appeal court documents.

DeFazio’s case was the first to result in a court ruling against WPPSS, deciding that municipal governments didn’t have the authority to enter into such agreements. In 1984, the Oregon Supreme Court eventually ruled that the governments did have the authority, but by then WPPSS, now known as Energy Northwest, had killed its projects.

“It was the biggest bond default in the country before the savings and loan [crisis] and until Wall Street bankrupted us in ’08,” DeFazio says.

In 1983, DeFazio was elected to represent Springfield on the Lane County Board of County Commissioners, the same year that Wooten led efforts to create the Eugene Celebration and the SLUG queen contest. That year, DeFazio also began a tradition that he’d continue for decades.

At the Eugene Celebration parade, DeFazio had the role of “slime scooper.” “They were dropping Saran Wrap and I would pick it up,” he says. “It was a huge hit.”

DeFazio kept that role of slime scooper throughout the lifetime of the parade. He walked behind a giant slug, designed to appear similar to a dragon parade prop longwu, picking up “political slime.” Although the parade ended in 2013, DeFazio says he still has the slug in a storage facility, hoping that the Lane County Historical Museum takes it from him.

During DeFazio’s one term as county commissioner, he became friends with Bob Warren, who would go on to work for DeFazio’s congressional campaigns and be his Oregon environmental confidant.

In 1986, Weaver left Congress to run for Senate, and DeFazio campaigned to take his place. He and Warren worked together on the trail, spending a lot of time on the road driving through the district. “Hectic isn’t a good word for it,” Warren says. “There was no sleeping and it was long, long hours, seven days a week.”

While running for office, DeFazio says he didn’t have much money in his bank account to campaign, and he didn’t know how to ask contributors for cash. So he says he and his team took an unorthodox approach: They used a phonebook to call lawyers to ask them for contributions, and they raised money through proceeds from garage sales.

Warren and DeFazio traveled Lane, Douglas and Coos counties in an Oldsmobile convertible but also in DeFazio’s infamous 1963 Dodge Dart, Warren says. Although the two spent a lot of time together, talking about forest policies and the campaign, what Warren remembers best is traveling in the Dart.

“They had roll-up windows, and on the passenger side, instead of having a regular crank on the side, it had a pair of Vise-Grips,” Warren says. “You had to move these Vise-Grips around in a circle to roll the window up and down.”

DeFazio owned the ’63 Dodge Dart from 1983 to 2003, and it’s been as part of his career as much as his policies. It even made a cameo in a 1996 Senate campaign ad. DeFazio showed off the Dart to NPR’s Car Talk hosts, and the hosts — Tom Magliozzi and Ray Magliozzi — later wound up talking about the car in a 2008 episode that featured someone who had bought it from him.

“We were visiting the Capitol a few years ago to attend a soiree for the benefit of National Public Radio. Peter DeFazio grabbed us, dragged us through the halls of Congress, and insisted that we come out to the parking lot behind the Capitol so he could show off his Dodge Dart,” Tom said in the episode.

Ray added, “And we’re glad to hear Peter has finally been able to let go of that thing.”

The 1986 primary election was a three-way race between DeFazio, then-state Rep. Bill Bradbury and former state Sen. Margie Hendriksen. On election night, the early Lane County results came in and showed DeFazio in the lead, and Bradbury called to concede. But the lead began to slip away from DeFazio. He says he went home, worried that he would lose the race.

The election ended with DeFazio winning 34 percent of the vote, Bradbury with 32 percent and Hendriksen with 31 percent.

Months later, when DeFazio was in D.C. as a newly sworn-in congressman after easily winning the general election, he was seated at a table with then-House Speaker Jim Wright. DeFazio told Wright’s chief of staff about his primary election. “He said, ‘That sounds like an amazing story. I’ve never heard of an election like that,’” DeFazio recalls.

That visit was also a sign for his wife, Myrnie Daut, that she wouldn’t be spending time in D.C. as a congressional spouse.

Wooten recalls Daut telling her how she attended an orientation for spouses of first-year members of Congress that taught the spouses proper etiquette. “She said that, ‘When we got to the part where they taught us how to curtsy, I knew I wasn’t going to permanently live in Washington D.C.,’” Wooten says.

Enlarge

A Congressional Friendship

In 1974, Les AuCoin won his bid to Congress to represent Oregon’s First Congressional District. He was the first Democrat elected to that seat, which has never been held by a Republican since AuCoin defeated incumbent Wendall Wyatt.

AuCoin held the seat until 1992, when he ran for U.S. Senate but lost to incumbent Sen. Bob Packwood (who would resign shortly after in disgrace). During AuCoin’s congressional tenure, he developed a reputation for criticizing the Reagan administration’s conservative policies and warhawk tactics in South America.

By the time DeFazio arrived in Washington in 1986, AuCoin had served six terms, and the two progressives became immediate friends, AuCoin remembers.

As peers in the House, the two collaborated during Oregon’s tense timber wars and fought for progressive policies during Reagan’s terms of austerity. Whether he was securing funding for mass transit or calling out Democrats siding with Reagan, DeFazio legislated like a wrestler, AuCoin says. “That’s how he tackled politics,” he says. “He can be your friend or he can be your biggest nightmare — and he’ll take you down in a minute if you’re not really ready.”

AuCoin says he was immediately impressed with DeFazio’s election to represent the Fourth Congressional District, a swath of Oregon that has long been a mix of liberals and conservatives, while maintaining a progressive agenda that he follows with policy substance — that “speaks worlds about his political talent,” AuCoin says. AuCoin calls DeFazio a “progressive lunch bucket Democrat,” a reflection of his blue-collar values. “He has a sense of populism that really relates,” AuCoin adds.

Although Reagan held the White House in the 1980s, the Democrats held the majority in the House of Representatives for most of the decade. Yet Democratic Party representatives voted along with Reagan to vote on his bills he wanted to pass, giving him the votes to pass budgets and reform Social Security and taxes.

AuCoin still refers to those Democrats as “boll weevils,” a term used to describe mid-20th century Southern conservative Democrats, and he says those party members still upset DeFazio. “If you want to get Peter roaring red angry, just talk to him about turncoat Democrats,” he adds.

In 1992, when AuCoin made a move for the Senate, running against Packwood. AuCoin recalls being on the other side of a mock debate with DeFazio, who was acting as the Republican incumbent. “I remember thinking, ‘Whoa, this guy could be a real handful for Bob Packwood,” AuCoin remembers. “He was a buzzsaw. I mean, he made me uncomfortable.”

If DeFazio wanted to run against Packwood, AuCoin says he would’ve let him. “He might’ve beaten Packwood,” he adds. AuCoin lost the election to Packwood, but it was not without controversy. In his memoir Catch and Release: An Oregon Life in Politics, AuCoin wrote that The Washington Post and The Oregonian uncovered Packwood’s sexual abuse of 10 women but didn’t publish the story until after the election. Packwood won the election but faced consequences for the sexual abuse allegations and would resign from office and would be succeeded by Sen. Ron Wyden.

What cemented the friendship between the two politicians for AuCoin is DeFazio’s work in legislating for the TriMet transit system in Portland.

AuCoin and former Sen. Mark Hatfield have long been credited for securing the funds for the TriMet transit system, overcoming the Reagan administration’s opposition to mass transit, Aucoin says. But without DeFazio, TriMet may have never received a large investment from the U.S. government.

Although DeFazio didn’t represent Portland in Congress, he was instrumental in his position as senior member of the U.S. House Public Works Committee to establish funding for the transit system. According to former lobbyist Richard Feeney’s account in TriMet’s Making History: 50 Years of TriMet and Transit in the Portland Region, DeFazio secured $516 million in the 1991 Surface Transportation Act. DeFazio’s push for that funding was the first time that a city the size of Portland had ever received such an amount for mass transit, especially for a project that didn’t have a final project estimate, according to the transit agency’s history.

“We couldn’t have appropriated the money and gotten it allocated if Peter had not authorized the project,” AuCoin says.

Hatfield and AuCoin both have their names enshrined along TriMet’s lines: Hatfield Government Center and AuCoin Plaza. Despite DeFazio’s legislative work to establish funding for the project, his name is missing. But AuCoin says DeFazio’s work hasn’t gone unnoticed. “What Peter got as a reward is the undying friendship of both Hatfield and myself and others in local government and transit officials who know what a significant accomplishment that whole thing was,” AuCoin says. “To be able to look back at the needs of the whole state is really quite a virtue.”

Enlarge

For the Trees Have No Tongues

Before several factors brought Oregon’s timber harvest to a halt in the late ’80s, DeFazio says that the Willamette region was harvesting around 4 billion board feet of timber a year — and was proud of it.

“The guy who was the head of the Willamette National Forest when I got elected had a sign in his office that said, ‘a billion or bust on the Willamette floors,’ in just one forest,” DeFazio says. “The agencies were stuck in the past.”

Oregon’s timber policy and protecting old growth sparked a battle between environmentalists and the timber industry. DeFazio’s peers who were involved with gatherings to find a solution say he led the efforts, which would become a White House priority under President Bill Clinton. He didn’t stop there, though, as he pushed Congress to protect wildlands throughout the state and helped environmentalists stop logging efforts during his career.

“When I ran for Congress, I said, ‘We’re cutting too much,’ and we need to save the old-growth forests,” DeFazio says of his first congressional campaign. “At that point, I had tremendous opposition from the timber industry.”

Years after his first election to Congress, the timber industry slowed down its logging activity after environmentalists sued the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service over its refusal to include the spotted owl under the Endangered Species Act. The owl was added to the threatened species list in 1990, but the agency didn’t follow regulations to protect it, according to “Travels with Strix: The Spotted Owl’s Journey through the Federal Courts” by Victor Sher, published in Public Land and Resources Law Review.

“It was a fraught moment for Oregon,” AuCoin says. “It was a political nightmare for everyone.”

Enlarge

In 1989, Oregon Gov. Neil Goldschmidt called for a timber summit, inviting Sen. Mark Hatfield, then-Congressman Wyden, AuCoin and DeFazio. The politicians met with environmentalists and timber executives to develop a plan to both protect old-growth forests and the spotted owl as well as find a way to lift the injunction that had frozen logging activity.

Despite the number of politicians present at the timber summit, Warren and AuCoin say that DeFazio was the most engaged in advocating for a forest plan that didn’t derail an industry. “While he’s a strong advocate for protecting old-growth forests — and always has been — and he recognizes all of our values at the same time,” Warren says, “he’s a strong advocate for blue collar workers, for people that work for a living.”

The timber conflict became a federal issue for Clinton to address when he was elected in 1992.

DeFazio started working with forest scientists Jerry Franklin and Norm Johnson on ways to protect old-growth forests.

The idea of not clearcutting big trees was a radical idea when Franklin wrote the 1990 article “‘New Forestry’ And The Old-Growth Forests Of Northwestern North America: A Conversation with Jerry F. Franklin” in The Northwest Environmental Journal. DeFazio says Franklin presented the concept of “new forestry” to environmentalists and timber industry officials. “But we didn’t make much progress coming out of that,” he adds.

In 1995, Clinton released his Northwest Forest Plan, a guideline still used today in managing federal lands, which DeFazio says he didn’t support. “Most of the environmental groups missed the fact that 35 percent of the harvest under the Clinton forest plan came out of old growth,” he says. “I said, ‘This plan isn’t gonna work. Neither side is getting what they want and it’s political because it’s so unbelievably complicated.’”

That same year, Clinton signed a bill passed by a Republican-dominated Congress that expedited salvage logging after a wildfire, bypassing environmental reviews. In Oregon, the proposed sale of 9,000 acres of salvage logging in the Willamette National Forest at Warner Creek, the site of a ’91 fire started by arsonists, became a battleground for protesters that would result in blocked logging roads, hunger strikes and mass arrests.

As documented in pickAxe by Tim Lewis and Tim Ream, in 1996 protesters flooded DeFazio’s office, demanding to meet with DeFazio and have the congressman get the White House on the phone. Although DeFazio wasn’t in his office at the time, the documentary shows protesters on the phone with someone in D.C. and cheering that the Clinton administration could kill salvage plans. The salvage plan was canceled months later.

Decades after Clinton’s Northwest Forest Plan, DeFazio says he tried to implement an old-growth program during the Obama administration. He wanted to take stakeholders and decision-makers on tours of old-growth forests. He also advocated for pilot programs to selectively thin 90-year-old naturally regenerated stands that are too thick, but the funding for those programs were reduced after facing litigation.

DeFazio kept fighting timber policies in D.C., and on the ground in Oregon, says Cascadia Wildlands Executive Director Josh Laughlin.

“There’s literally dozens of timber sales over the decade that he got involved in and his staff got involved in that was critical,” Laughlin says. DeFazio and his staff stayed active in writing letters in protest of timber sales to the U.S. Forest Service and the Department of Agriculture, visiting sites targeted for clearcutting, he says. And DeFazio took all that information and worked to lobby federal agencies to try and stop timber sales.

DeFazio worked to preserve large regions of Oregon’s wilderness — such as the Devil’s Staircase in the Coast Range — but also fought the federal government on individual timber sales, Laughlin says. And he was active in the LandBack Movement, the push to return stolen lands to Indigenous peoples.

While in office, DeFazio brought together his passion for the Oregon environment and his penchant for serving his constituents to challenge timber harvesting of old growth forests, Laughlin says. “Peter is a conservationist at heart and really went to bat for residents in Oregon’s Fourth Congressional District who shared the values he held closely,” Laughlin says. “He’ll be remembered as a champion for wildlands, waters and the wildlife in our special region. He’ll have huge shoes to fill.”

Enlarge

Looking to the Future

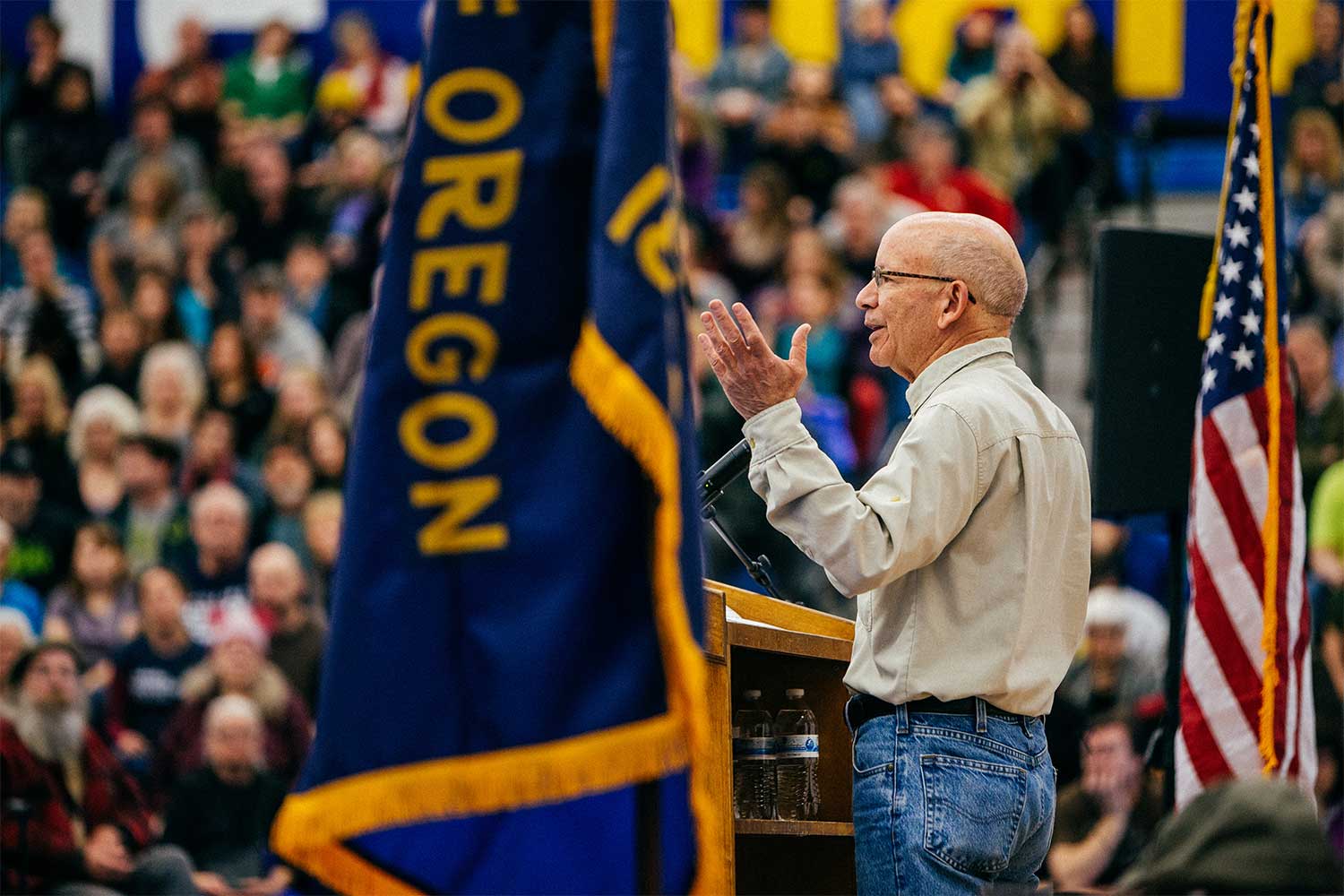

During his 36-year career in Congress, DeFazio has grappled with presidents, passed progressive legislation and served as a champion for Oregonians — whether they’re in his district or not. His legislative history is so long that he says, reflecting on accomplishment memos that congressional offices send out every year, he’s forgotten some of the work he’s done.

Before retiring, he says he had more on his laundry list of legislation to do, and that’s why his wife, Myrnie Daut, thought he’d never leave office. “Even when I told her I was going to retire, she didn’t believe me until we did the public announcement,” he says, referring to his Dec. 1, 2021, retirement press conference.

He hasn’t settled on any plans yet, as he had been too busy finishing his final term, but he has some ideas.

The congressman, who will be remembered for his tenacity in the House and exhibiting a style of legislation akin to his days of wrestling, says he’s looking at ways to lend his knowledge of lawmaking to environmental groups he supports. He specifically wants to assist advocacy groups that are standing up against the extermination of wolves.

And DeFazio is still looking at ways to continue to hold Wall Street and corporate greed accountable. He says he’s been working on a book about deregulation and how it went from smaller sectors, telecom and aviation, all the way to large industries, such as Wall Street, to free trade agreements.

But what he talks about most is exploring Oregon’s beauty while retired, the lands he fought as a congressman to preserve. It’s the scenery that brought DeFazio to Oregon in the first place nearly 50 years ago after stumbling upon an article about the Pacific Northwest in the travel magazine Holiday, choosing the Beaver State over graduate school opportunities in Albuquerque, Boulder and San Diego. “I got here and didn’t know there was any place like this,” he recalls. “Fell in love and thought I’d died and gone to heaven.”

After a recent back surgery, he says his days of lugging a 55-pound backpack may be over, but he still has the dream of hearing a wolf in the wild. And while on summer recess in 2022, two days in a drift boat rekindled a desire to spend more time on nearby rivers. “I think I need another drift boat for retirement,” he says. “And I got to learn how to fly fish again and have a lot more fun.”

This article has been updated. A previous version implies that the Saturday Market was one of Cynthia Wooten’s projects. The group that started Saturday Market met and held the first-ever gathering at Wooten’s coffee shop, the Odyssey Coffee House.