On the day of the University of Oregon’s 2022 spring football game in April, many students were preparing to cheer on the Ducks. Junior Claudia Santino was preparing for her band’s first gig.

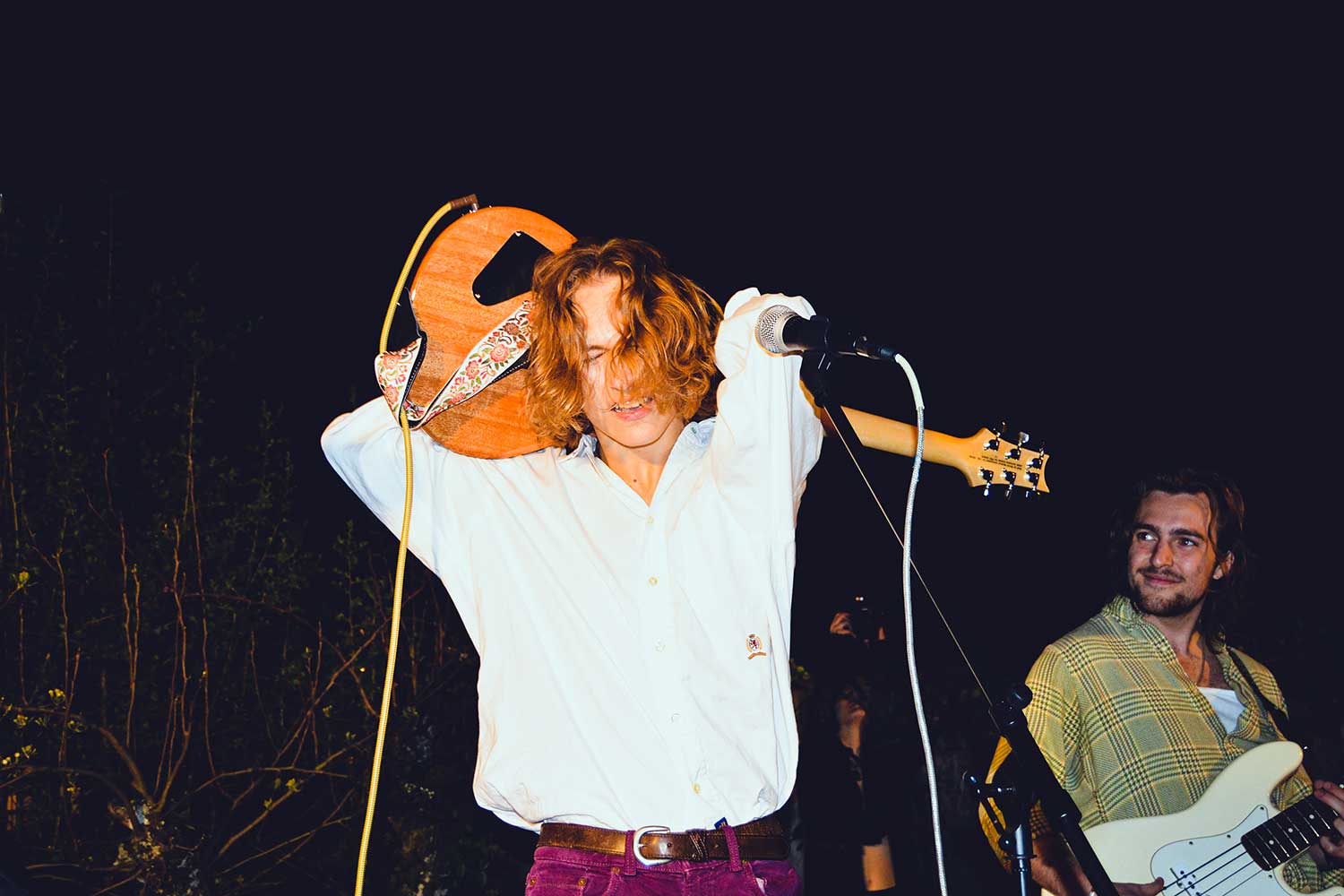

Santino was just a spectator in Eugene’s rich DIY music scene until she began singing with GrrlBand last spring. She spent her fall and winter regularly attending house shows, concerts held in living rooms, basements and yards. While navigating the crowds at the Blue Dragon, a house venue hosting a concert, she ran into classmate Codi Farmer, who talked about forming an all-woman rock band that needed a vocalist. Santino’s vocal reputation preceded her, and she joined the band. GrrlBand’s first gig was one week later, hosted at the home of a friend of the band.

GrrlBand kicked off the night’s line up in front of about 100 people packed in the fenced-off front yard. The band Mommy went on next, and about half way through its set multiple police cars appeared in front of the house, lights flashing with a booming megaphonic voice telling people to get off the street — which Santino says caused confusion, as there was no one in the street, and only a small number on the sidewalk outside the yard.

Enlarge

After what Santino says was an unclear conversation between the show’s host and police, disappointed bands began packing up gear, a premature ending to the gig. Police slowly left the scene, but some police cars circled the end of the street as if waiting for legal violations to happen, Santino says. No citations were given that night — but they were lucky.

Many houses, including the popular Blue Dragon, have received hefty fines for throwing concerts. Former Blue Dragon booker Annika Bernhardt says she and her roommates received a combined total of $2,100 in fines at their final show, plus court fees.

Eugene’s underground music scene is certainly no stranger to noise complaints or visits from the police; the scene has experienced periods of crackdowns before. Recently, though, frustrations are growing as some in the music scene say they are experiencing being shut down more frequently now than before the pandemic. UO students say the Eugene Police Department is cracking down on loud gatherings near campus, where many of these shows take place.

Local musicians and house venue owners say they work to be respectful, law-abiding and in recent years safe from COVID-19, but in the eyes of law enforcement, concerts are no different than rowdy college parties.

‘More than just kids throwing a party’

Eugene’s basement music scene has a long history. During the ’90s, punk music oozed out of many houses around Eugene. Scene veteran Saxon Wood says there was even an iconic show played by the influential punk band Black Flag in a Eugene basement, with about 100 people crammed inside.

“When I first came to Eugene there were a number of house venues that really never seemed to get bothered at all,” Saxon says about police shutting down shows.

While punk is no longer the most popular genre in Eugene, the tradition of living room, basement and garage concerts is still alive.

The scene was especially vibrant in 2019 and early 2020 before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, after a lull in 2017 and 2018. Spencer Misfeldt, a guitarist for local band Candy Picnic, remembers there being three to four shows a night on the weekends. Several people, including Misfeldt, recall having multiple competing shows happening at various places on the weekend.

“We would be playing at a house venue,” Misfeldt says of Candy Picnic in 2019, then a recently formed band, “We’re like, ‘Oh well, Novacane is playing here and Laundry is playing here, no one’s going to come to our show because there are all these other shows going on.’” Laundry and Novacane were popular bands in the local scene that moved elsewhere.

UO student Sigi Allen helped run the short-lived Alder House in 2021 and was a frequent flyer at shows during her freshman year in 2019, before the pandemic sent many students home and shut down much of the music.

Allen remembers being “wide eyed and so fascinated” by everyone involved in house shows, from those running the house venues to the performing musicians as she would bounce around at different shows on the weekends. She says it felt rare for shows to be shut down and fined.

“Nowadays, people are like, ‘Oh, that was a really fun house, but we can’t go anymore because, you know, the cops showed up and fined them to the point where they’re too scared to have shows,’” Allen says. She cites the lack of experience at shows that get shut down as the reason why she and her roommates weren’t afraid to start the Alder House venue at the start of the 2021 school year.

As the name implies, the Alder House was on Alder Street within walking distance of UO. Allen says her house was the first to come back after the pandemic shut down, which contributed to its popularity. It was a sought-after house by many concert-starved bands and music lovers. Allen says she worked to cover all her bases, from COVID to respect towards her neighbors.

Allen and her roommates gave all immediate neighbors handwritten notes to inform them of the house’s upcoming events and provided a phone number to contact in the house. This was an effort to maintain good relationships with her neighbors and avoid noise complaints.

The Eugene city code defines a noise disturbance as sound that “injures or endangers the safety or health of a human, annoys or disturbs a reasonable person or normal sensitivities, or endangers or injures personal or real property.” The code says that noise from “sound producing, amplifying or reproducing equipment” that bleeds into other housing units is unlawful between 10 pm and 7 am.

For the Alder House’s third and final show on Halloween weekend last year, Allen says she had printed around 200 notes to hand out in a five-block radius of the house. Allen says she also talked personally with a manager at nearby Sundance Natural Foods, who gave approval for the event and was willing to tell that to the police.

“We wanted to make sure that everybody knows that it’s a three-hour block, maybe once a month, that we’re going to be making loud-ish noise,” Allen says.

Despite Allen’s efforts and the support of several of her neighbors, the Alder House backyard concerts — some with around 300 people — resulted in noise complaints that ultimately shut down the venue after three shows. When a neighbor told Allen before the second concert that they would call the police after 10 pm for the second concert, Allen assured them it would be wrapped up by then like the last concert. When the police came close to 10 pm, Allen said in a written statement that the venue escaped a fine because the music was either wrapping up or stopped abruptly when police arrived.

The police officers who arrived told the hosts that the concert had to stop immediately, citing the noise ordinance, Allen says. The officers also told Allen this was the third response to her address; she says it was the second. An email warning was sent to Allen by UO a month after the first concert, but she says it referred to a separate house party weeks after her concert and was wrongfully attributed to her house. Allen and her roommates decided hosting any further shows would pose too great of a legal risk to the members of the house.

Allen says the response to her house was one of the first serious shut downs, and they were lucky to not get any fines.

“I was really passionate about [running house shows], but it was just really frustrating because it’s like no matter what we do the police will always see this as a bunch of kids who are trying to get drunk,” Allen says.

Santino of GrrlBand, like several others in the community, also believes that there is a strong sense of community and identity in the music scene. To her, music is similar to what sport is to athletes. “It’s just community, and it’s just what we like to do,” Santino says.

Enlarge

EPD, the law and house shows

Most of the music scene is aware of the second part of the noise ordinance prohibiting loud noise from 10 pm to 7 am and actively works to respect it, like Allen did. But EPD Cpt. Doug Mozan says this section of the noise ordinance is commonly misunderstood.

“The noise ordinance essentially specifies that if a person of reasonable sensitivity hears a sound that offends them, they can call at any hour,” Mozan says, adding that the 50 feet is about the distance from most people’s front doors to the sidewalk — not a hard bar to meet. That is especially true with drums, cymbals and bass amps, all common in rock bands.

Mozan says that the police don’t get involved unless there is a noise complaint from the neighborhood. He says in his experience, neighbors “are often more sensitized to sound when it’s a repeated event,” and even more so when the sound is accompanied by “ancillary things” like people coming and going from a house “like a party scene,” and when parking is impacted. He says people can take steps like reaching out to their neighbors to avoid a complaint, and that might work once or twice, but not in the long run.

On Jan. 28, 2013, the Eugene City Council passed its “social host ordinance,” citing “oversize, disorderly gatherings and parties involving alcohol” as a chronic problem for the city. The ordinance “holds individuals and property owners accountable for unruly events or social gatherings,” defining an “unruly gathering” as one that involves the serving and consumption of alcohol, and two behaviors from a list including harassment, assault, disorderly conduct and noise disturbance.

The fact sheet says fines can be given starting on the first violation of the ordinance, and on “second and subsequent violations within a 12-month period,” hosts and organizers can be held responsible for the cost of police and emergency response. Fines range from $375 to $1,000.

“If you continue to have events, at some point we’re gonna get a call, and when we get that call, frequently, it’s from someone who’s just had enough,” Mozan says. “And they indicate that they’re willing to prosecute for the noise ordinance.” He also says it is common to get a call from someone that is afraid of retaliation from a prosecution, and in those cases the police department will act on that person’s behalf.

A records request from EPD tallying the police responses to “loud noise” or “loud party” in the West University neighborhood, where many house shows and house parties are held, shows 371 responses in 2018, 363 responses in 2019, 375 responses in 2020, and 451 responses in 2021. In the South University neighborhood from 2013 through 2021, the response numbers are 117, 142, 137, 140, 133, 109, 135, 128 and 102 respectively.

The numbers in West University do reflect a spike in responses that confirms music supporters’ belief that house shows are shut down more now than in 2019. Some musicians and concert hosts in the music scene say there were fewer house venues to play at in 2021. Because there have been fewer shows since the start of COVID-19, those in the music scene say police are responding to more venues than in previous years.

Enlarge

EPD — and likely those who call in noise complaints that shut down house shows — categorize DIY concerts as parties, so in these numbers it is impossible to separate which of these events are standard college parties, and which are house shows.

Mozan says the reason for the lack of discernment is that the effects of a house show and a party are essentially the same: loud noise, price of admission and a large number of people coming and going. Some people in the music community believe this view minimizes the effort and professionalism that go into a house show.

Athena Nguyen, who used to help run a venue called the Guest House for a brief time before it permanently shut down fall 2021, says shows at her house often had strict set times that generally ran from 8 to 10 pm on a weekend. To her knowledge at the time, this followed the noise ordinance law, but she says the police did explain that this is not the case after neighbors called the police. She says bands were always respectful, and often brought designated security with them to monitor the audience and ensure a safe gathering.

Like Allen, Nguyen and her roommates worked with people in the neighborhood and were supported by some, but a neighbor upset by the loudness of the concert did threaten to call the police if it was not wrapped up by 10 pm. The police came, but to an empty backyard as Nguyen made sure everyone left before the police arrived. She also notes if music gear is present, then police can confiscate it. Wood remembers this happening to a popular house venue across from campus called the Campbell Club (which is also a housing co-op) many years ago.

Allen says no one should be shamed for wanting to attend a party or a house show. But, she says, the purpose of a house show and the purpose of a party are different.

“I think it’s based in music and based on encouraging people to become a part of it, or encouraging people to support local artists and be excited about it,” Allen says. She believes that being able to see and talk to local musicians at shows or in class makes the creative outlet feel accessible. Bernhardt says that she also often hosts shows that are community fundraisers.

While bars are an option for some bands, this doesn’t work for many underage bands and fans. Some all-ages venues in town include Slice Pizzeria, WOW Hall, McDonald Theatre and Alluvium. Slice and the Alluvium are in the Whiteaker area, and WOW Hall and McDonald Theatre are near downtown. The UO Music and Concerts club also organizes concerts on campus with some local acts, but not on a weekly basis.

Mozan, a musician himself, says he sympathizes with the scene’s desire to participate in a form of self expression, and recommends that bands find some of the all-age venues in town to play at or rent out. He suggests crowdfunding to rent out a venue for the purpose. For college student attendees without cars, he suggests getting rides from a rideshare app or a friend.

Bernhardt says that Mozan’s suggestion is an ideal that many bands would likely enjoy, but it doesn’t reflect the reality of the resources students have, financial and otherwise.

“There are festivals and shows that do happen at places like WOW and at Slice, or in community parks,” Bernhardt says. “But those require a lot more money than I think a lot of us are able to put into things like this.”

Wood, who used to volunteer at an all-ages sober venue called The Boreal near the Whiteaker before it closed down in 2017, says that even with all-ages venues there is still a place for house shows, as a place for new bands to experiment with their sound in front of friends. Bernhardt agrees, adding that the house show scene is an easy way for new bands with no show histories to start forming an audience to be able to get into the bar scene.

“I do think that underground music is essential to the music community,” Bernhardt says, “to finding new artists and to giving people a space to create, and give show goers a space to participate in someone else’s music.”

Enlarge