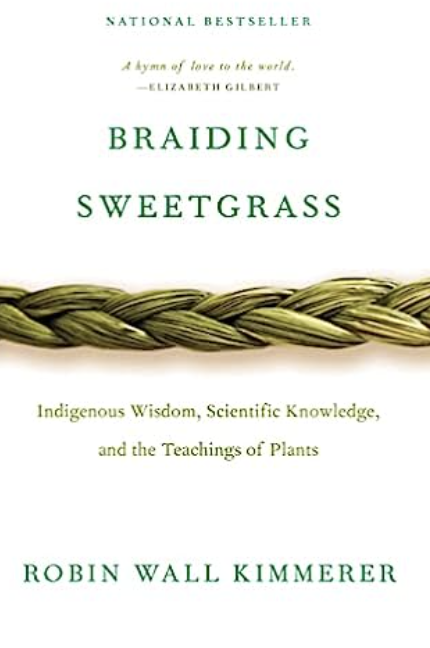

Our Shared Breath: Creativity and Community is on view at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art through October. The show is part of Common Seeing, an annual series that corresponds to the campus-wide Common Reading program at the University of Oregon. This year, like last — the reading was extended for an additional year — the UO’s Common Reading is Robin Wall Kimmerer’s national bestseller Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants.

Kimmerer is a distinguished teaching professor of environmental biology at SUNY in Fabius, New York, and a member of Citizen Potawatomi Nation. Her text weaves together different ways of knowing: essays that incorporate aspects of memoir, science, her Native American culture, identity as a woman and perhaps most of all, love of nature.

In a talk at the UO in 2022, she drew on the Potawatomi language to suggest, “I propose that we adopt a new pronoun, an animate pronoun, so that we might speak of Earth beings (including my beloved plant teachers) in plural form as our ‘kin.’”

As a Common Reading, Kimmerer’s book is handed out to incoming first-year students and to all faculty. There is no requirement that faculty at UO incorporate the text into their teaching, but many do. From history to philosophy, to ethnic studies to dance, the list of courses utilizing Braiding Sweetgrass is long.

Co-curators Danielle Knapp and Zoey Kambour chose the art. Knapp, who is the McCosh curator at JSMA, says they selected artworks not to illustrate, rather to complement the themes presented in the Common Reading. Each of the six artists in the exhibit are identified as either Indigenous or American. They are: Melanie Yazzie (Diné or Navajo), Sara Siestreem (Hanis Coos), Rick Bartow (Mad River Wiyot, 1946 – 2016), Lehuauakea (Kanaka Maoli), Ryan Pierce (American) and Malia Jensen (American).

The artists are mostly represented by just one or two works, so you might think this is a small and simple show that’s quick to view. The opposite is true. The art here represents bodies of work as complex and intriguing as Braiding Sweetgrass.

Bartow’s artworks — straightforward depictions of birds — were done with ink and a stick. The late artist is well known in Eugene for his transformative portraits placing humans within the frames of other animals. Knapp says she appreciates any excuse to retrieve his art from the permanent collection. Here, even these straightforward “stick” drawings are expressive, and the inclusion of his art lends a historical weight to the show.

Lehuauakea is the only artist whose making of work for this show was supported by the museum. Each piece in their series depicts a traditional Hawaiian pattern, done in earth pigment on kapa, a traditional Hawaiian barkcloth. The earth for the pigment, though, was obtained from different lands corresponding to five Native cultures in Oregon (which they refer to as “the so-called state of Oregon”): Nehalem, Yahooskin, Tillamook, Chinook and Umatilla.

Lehuauakea is the only artist whose making of work for this show was supported by the museum. Each piece in their series depicts a traditional Hawaiian pattern, done in earth pigment on kapa, a traditional Hawaiian barkcloth. The earth for the pigment, though, was obtained from different lands corresponding to five Native cultures in Oregon (which they refer to as “the so-called state of Oregon”): Nehalem, Yahooskin, Tillamook, Chinook and Umatilla.

Ryan Pierce’s two paintings in the show, “The Seal of Strength in Solitude” (2017) and “The Seal of the Hard Harvest” (2018), are executed with Flashe (a brand of vinyl paint) on paper in an inviting illustrative style. They are included, courtesy of Elizabeth Leach Gallery in Portland. As beautiful as they are, they symbolize an art practice that extends far beyond any gallery walls. The paintings are images from Pierce’s 2018 “walkable artist book” called The River in the Cellar, which is a book without pictures.

It’s the reader’s mission, should they accept it, to find the missing art.

This mission is part of a story in which the reader/art-finder is aligned with the narrator of the book in trying to cope with climate chaos and to become a citizen of the desirable city-state of Multnomah. To become a citizen, you must follow the text to different sites in Portland, all in natural areas near water, and locate prints of these two paintings and nine others.

Pierce is a fan of Braiding Sweetgrass and has used it as a text when leading a unique artist residency at Signal Fire, an accredited school and wilderness program that he and ex-wife Amy Harwood co-founded in Portland. The program ran about 10 years. Pierce is currently chair of the Low-Residency MFA Program in Visual Studies at Pacific Northwest College of Art, and would like to establish another wilderness appreciation art residency.

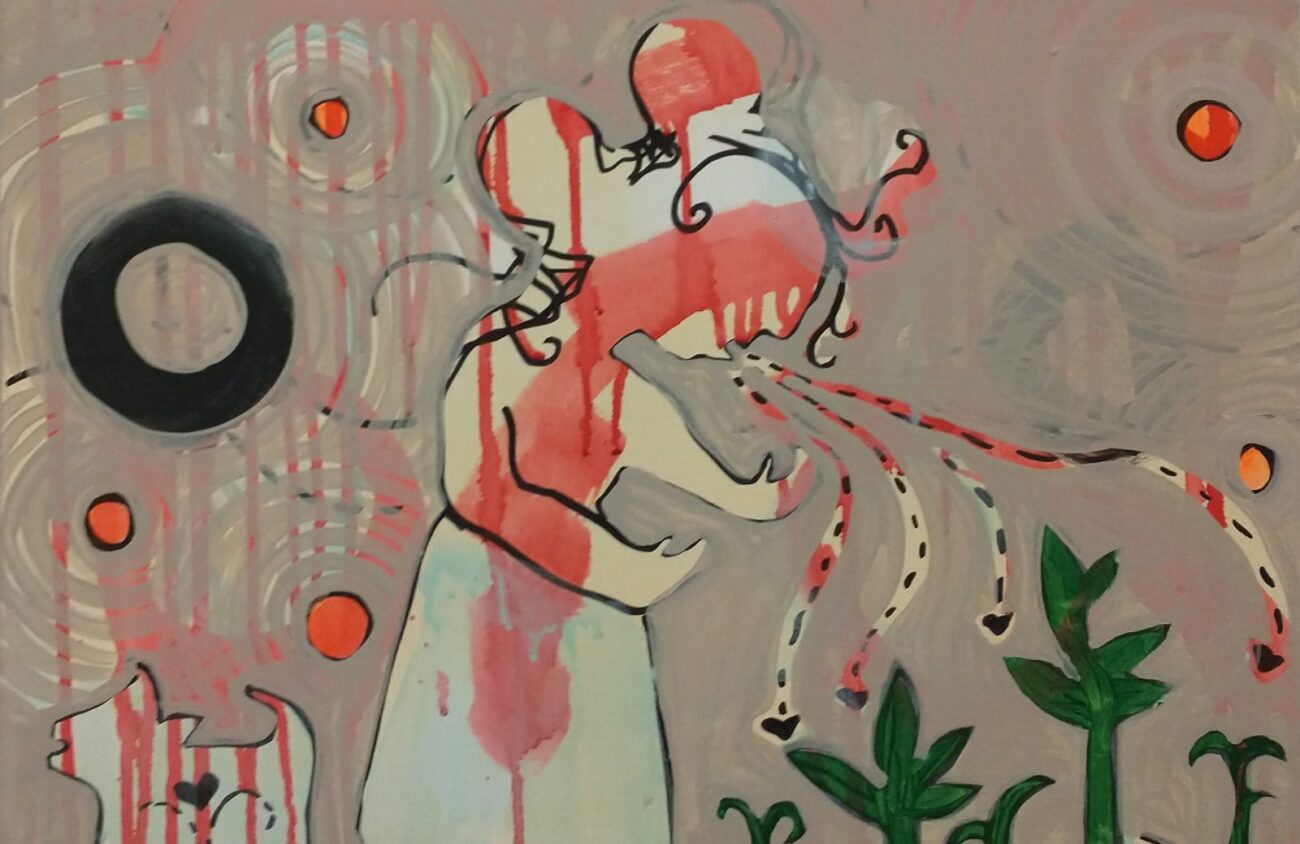

Art in the show isn’t meant to be illustrative, but Melanie Yazzie’s single contribution, an acrylic painting titled “Pray, Talk to Them,” is illustrative of the heart of Braiding Sweetgrass. Initially on loan from Glenn Green Galleries, it has since been purchased by JSMA and is the first work by Yazzie in the museum’s collection.

The painting reflects love — and kinship — between a woman and the plants growing in the ground beside her. The actions identified in the title are made clear by dotted lines moving from the woman’s mouth to each plant.

It is a “delicate” painting, the artist says.

When I meet Yazzie on Zoom she is exactly on time. Her punctuality is purposeful, she says. It’s meant to combat the stereotype about “Native time.” She is often early to meetings, and for deadlines, too.

Originally from Ganado, Arizona, in Navajo Nation, she is in Boulder, Colorado, when we meet, where she works as a professor of printmaking at University of Colorado. At first, she doesn’t remember which work she has in the exhibit. Responding to my surprise, she says, “I have about 30 artworks out now. It’s hard to keep track.”

What is the secret to her success as an artist?

She attributes the fact that her “art career has always taken care of itself” to the passion she has for communicating her culture through art. Combating stereotypes is part of that, especially negating the stereotype that comes from anthropology, she says, which is the idea that native people are vanishing.

Her goal to let people know that her culture is still very much alive has taken her around the globe, sharing her art as she “walks in the world as a contemporary Navajo.”