It’s 6:30 am. The smell of home-cooked bacon, eggs and hashbrowns forms in the kitchen, eventually wafting around the corner and into the two floors of dorm rooms. There, 50 groggy high schoolers shuffle in and out of the bathrooms, getting ready for the day.

Thankfully, it’s Thursday — the last day of the school week. After a hopefully quick day of classes, hanging out with friends and sports, the students’ parents will drive anywhere from one to three hours to pick them up and take them home for the weekend.

Welcome to Crane Union High School (CUHS), home of the Mustangs and the oldest public boarding school in Oregon. The high school’s 81 students come from all over Harney County — an area in the southeast corner of the state that’s about the size of Massachusetts. From kindergarten to eighth grade they attended school at a number of small — many with only one room — school houses around the county, including Frenchglen Elementary School (six students, two teachers) and Double O Elementary School (three students, one teacher).

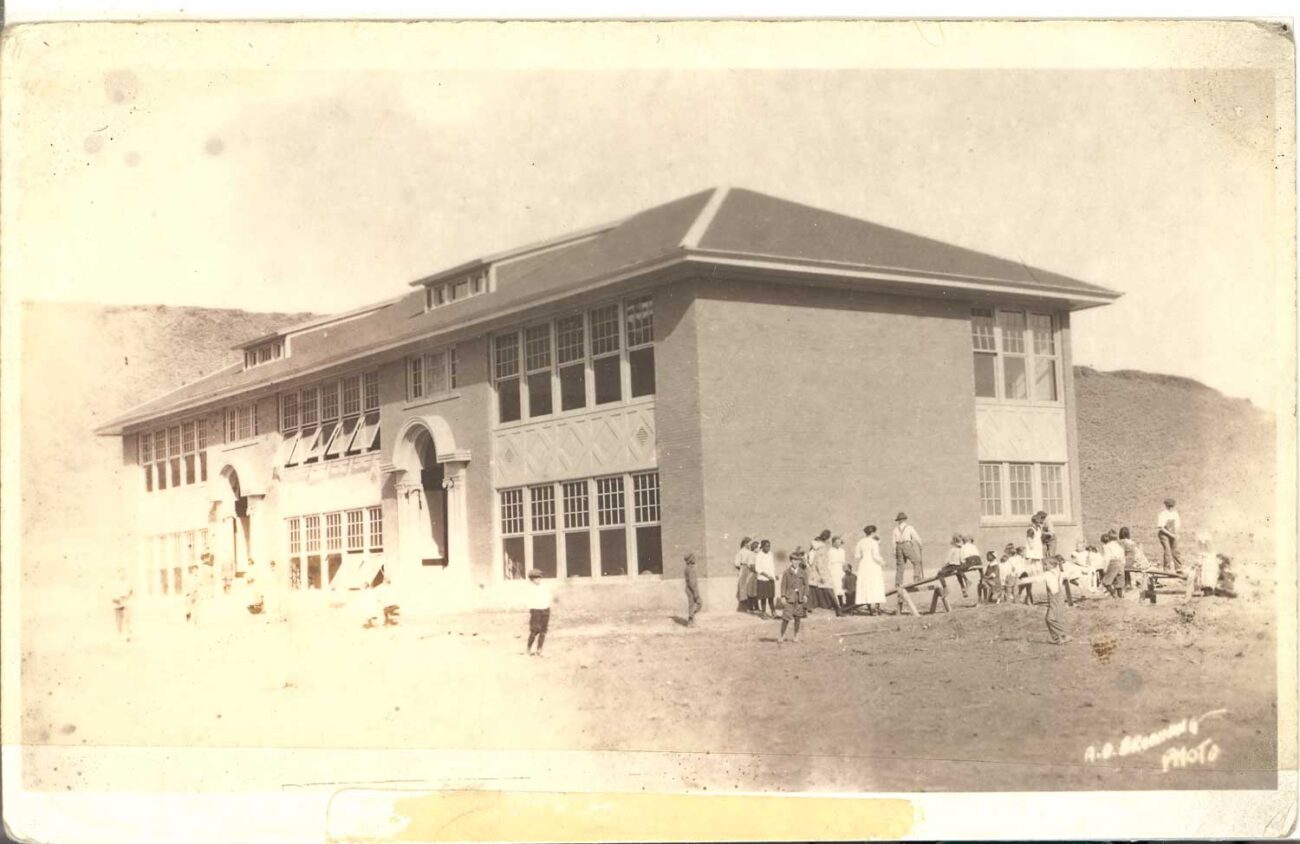

This unique, tight-knit school community was born about a hundred years ago, out of the need for students in this vast rural area to have access to education. Many students are kids of ranchers who live on long stretches of land far away from town.

“It’s very neighborhood-ish, even though it’s 10,000 square miles,” says CUHS Principal Eric Nichols. CUHS was once the only public boarding school in the lower 48 states. Now there are a handful of others, some even seeking to attract international students.

A photographer from Eugene Weekly and I sat down with Nichols in his small office one day last May to learn more about the community of Crane and the school that everything is centered on. The walls are covered in pennants from different colleges Crane High School students have attended, a list that includes everything from the University of Oregon and Portland State to Harvard.

Enlarge

Nichols is tall and has short cut red hair — physical attributes that match his energetic, friendly demeanor — and he is not dressed like your typical Harney County cowboy (although he does confirm later that he has a hat and boots that he saves for special occasions). Instead, he wears tennis shoes and a three-quarter zipped sweater.

Nichols was raised in Baker City, a small town in the upper east corner of Oregon. He has been the principal in Crane for five years. Previously, he worked with the Harney Education Service District. An ESD is a regional operation that helps connect school districts to state and national resources. He has also spent time as a principal in Burns and a handful of years as a teacher in Boise, Idaho.

“I like working with kids,” Nichols says. “I left my job at the ESD so I could work again with kids.”

Nichols says something the school really prides itself on is listening to student voices. He says they have an assembly at the beginning of the year and he asks students what they want to see happen. Classes come together to contribute something for the list. Some classes ask for tacos every Tuesday, some ask for certain electives, and others ask for a UFC cage fight.

“Two years ago, I took that list and I posted it,” Nichols says. “And we tried to accomplish everything. The cage fight was on the list, and it was the very last thing.”

Nichols assures us that they didn’t actually have teachers compete in a cage fight, but explains it was more of a cage-fight-inspired Jeopardy game.

“We really value student voices. And we tried to do it [the UFC fight] realistically, but they knew we valued what they wanted.”

Nichols says that in the urban-rural divide, there is a misconception that people living in rural areas are out of touch with the modern world. But in this age, everything is connected, meaning the divide is not as drastic as it once was.

“Yes, it’s 30 minutes to go get toothpaste here, but Amazon Prime exists, right? We all make our Costco run, just like everyone else. Costco might just be closer for you,” Nichols says.

He says there are fewer boarding school students at Crane than there were 30 years ago, as population in the county has been declining since the 1980s. Like all places, some people like the quiet life here and choose to stay, embracing the ranch lifestyle. Others have moved away, either giving up the family ranch or seeking different opportunities.

“There are still super big positive things here,” Nichols says. “We took 35 people to Washington D.C., giving them an experience they’ve never had before. Just like in Portland, people in Washington D.C. are unfamiliar to them.”

One of the greater challenges of running the school, he says, is showing kids the different opportunities that exist in the world. Many of them have not had the chance to experience places outside of Harney County.

“I think one of the biggest challenges is that exploration of the outside,” Nichols says. “Harvard does exist. Eugene does exist, Portland does exist. There are all these opportunities out there that do exist, and there just aren’t some things that come through here.”

Enlarge

A historic community

In 1931, Crane High School became a boarding school, which was one of the only two tax-supported dormitories in the United States. Over the years, different facilities were added onto the school — laundry rooms, lounge rooms, teacher housing. A fire that started in the school gym in 1967 destroyed most of the buildings. Two years later, the school was up and running again.

During the 1930s, Crane was a thriving community in Harney County because it was a railhead for the Union Pacific Railroad. The town boasted a movie theater, a bank, a newspaper, two general stores, five restaurants and a hotel. Now there is one store, the school, a few churches and no restaurants. The latest census counts 94 residents, not including the boarding students.

Although Crane is a shadow of what the town used to be, it still stands. Instead of the school being in the center of Crane, the unincorporated community of Crane now centers on the school.

Nichols introduces us to Gennie Cargill, who has been around the school for more than four decades. She is the administrative assistant and office manager of the high school, the air traffic controller who keeps everything moving smoothly. An amiable middle-aged woman with short blonde hair and black-rimmed glasses, it’s easy to see why Cargill ended up in this position. She gives the impression of a super multitasker — bouncing from answering my questions, to digging for a paper in a filing cabinet, to making a brief phone call to confirm to a concerned student that the buses haven’t left for the day.

Cargill is originally from the nearby community of Lawen, now a ghost town with a handful of rundown buildings. She is a graduate of Crane Union High school and even met her husband — also her high school sweetheart — here. Her kids also attended the high school.

Enlarge

“I loved living there my freshman and sophomore year, because it was like a slumber party,” Cargill says. “By the time I graduated, I was a little tired of it,” she adds, laughing. Not much has changed in that respect. Cargill says that it’s a big shift for teenagers to suddenly move away from home.

“That dorm throws a big wrench in their life. They are now staying here overnight. And I live right across the grass from them,” she laughs.

Cargill has some traditional views about education. She says students often get caught up in the hurriedness of life and are missing things because they are on cell phones so often.

“I see a huge detriment to kids with those phones,” Cargill says. “It’s like, ‘Oh let me text them,’ instead of walking across the hall and talking to them. I think that’s a challenge because I don’t think they know the damage that’s doing to them.”

Cargill says it might be because of her age, but she likes to run things a little more strictly, explaining that the no indoor hats school policy is because of her.

“That’s a respect issue. You know, they can have them in the dorm, but not in where they eat,” she says, adding that her main issue is when students wear hats in class and keep them pulled down so the teachers can’t see their faces.

A school like any other

Around school grounds, it’s evident Nichols is seen as friendly and approachable. As we tour the different buildings, students walk up and pepper him with questions ranging from when an event is to asking him to sign paperwork. He does so willingly, taking the time to acknowledge each student.

The number of students and staff may be fewer than most schools in Oregon’s west side, but Nichols says they still try to offer their students a variety of learning opportunities and experiences. There is a woodshop, a welding shop, a classroom set up to learn different medical procedures, such as how to stitch up a wound, and a sawmill. Students have even helped build tiny houses, one of which is displayed for sale next to the running track.

Nichols tells us that a number of years ago, rodeo used to be an official school sport. It was eventually disbanded due to liability concerns. A number of students still participate in rodeo events outside of school.

Because of the school’s size, staffing for different specialties can ebb and flow. Right now there is no choir or band program, although it has existed in the past.

“Programs are people, and it gets hard to build systems,” Nichols says. He says although they don’t have electives like band and choir right now, the school offers other courses such as videography, welding and a student news channel.

We make our way into the dorm building, where we are regaled with tales of full breakfasts and steak dinners. Around the corner from the cafeteria, the students have access to a carpeted lounge area with an assortment of couches, a television, and a pool table. We peek into a few rooms, most of them the same size or bigger than a University of Oregon dorm room. In the past, the rooms could house up to four students, but with current enrollment there are only two students per room. Girls live upstairs and boys live downstairs, but no one is allowed to be on the wrong floor.

Nichols takes us into the school gym for a brief moment, and I’m immediately struck by how shiny the floors are. Silhouettes of three mustangs are painted onto the polished surface. Nichols says they redid the gym floors recently and that students designed the painted image.

The high school offers a variety of sports — an eight-man football team in the fall, with basketball and wrestling in the winter. Some sports are offered in collaboration with Burns High School — the only other high school in the whole county — such as softball and cross country.

Many families have to drive an hour or more just to see a home game at the school. Teams will travel at least two hours one way for an in-league game, and sometimes up to five hours for non-league games that may even bring students over to the west side. The past two years, the boys varsity basketball team placed first in state in the 1A division. CUHS also has several state titles in track and field.

Enlarge

Soon after the tour, Nichols leads us over to the track, where the elementary students are competing in different track and field events, while excited parents watch in an annual gathering called “play day.” Kids of varying height, gender and attire line up at the start, anticipating the starter pistol. These runners are wearing everything from running shoes, to jeans or even muck boots.

We find students Brady Otley, Kayli Dunten and Tanner Joyce, sophomores at the high school who are currently boarding. They are dressed casually, with Dunten sporting a commemorative Washington D.C. T-shirt — a reference to Crane High School’s recent trip to the nation’s capital.

Dunten says moving into the dorms at age 14 wasn’t much of a challenge, because she got to see her siblings in school.

“Sometimes, it’s hard,” Otley adds. “You don’t have your mom when you need something.” He also says that there is a limited number of things you can do, and that students can only go so far, so sometimes that is frustrating.

However, Dunten verifies the dinners at the boarding school are great — a direct contrast with my cafeteria meals when I was in school.

“But the best part is all the time I get to spend with my friends,” she says, smiling.

Teenagers living in close quarters with their peers can be great for friendships, but also complicated. Although Nichols says students mostly get along, conflicts are also unavoidable.

“Sure there’s drama school, and it’s a small community, but they get along,” the principal says. “You get pissed at each other, but you get over it in a hurry because when you eat, you eat together.”

At the end of the day, he says, in this unique style of community, students have to learn the life skills to get along with each other because there aren’t many places they can hide from conflicts with one another. And with any problem, everyone knows everyone’s parents, so everyone takes care of each other.

In the crowd of all ages at the track meet, I am also introduced to Charis Hall, an eighth grader at Crane Elementary School, which shares a campus with the high school. She is dressed in a simple black shirt and jeans and holds a camera. Hall says she is taking pictures of the different races and field events on behalf of a teacher. Hall will be attending CUHS next year, though she won’t be boarding because she’s a Crane local.

Hall explains that her family moved to the area from Lincoln City several years ago. She says she hasn’t had a problem making friends because her dad is a pastor at a local church and it’s a small community, but her warm and self-assured personality speaks for itself even if she’s an odd fit here in the Wild West.

“Mostly I like to read,” she says, tucking a strand of straight blonde hair behind her ear. “Very boring because in essence everyone else just likes to play basketball or ride horses. We don’t have any of that so I just like to read.”

As far as nerves about starting high school, she says she is ready to get it over with. Since she currently attends Crane Elementary, her new commute really only consists of walking a few buildings over. Hall says she is already taking a high school math class anyway.

“I’m not really excited,” she says matter-of-factly. “Just ready for it.”

The Long Road

The next few days, as the students from Crane are home enjoying their weekend, we explore some favorite spots in Harney County. Even in May, the weather is unpredictable. The desert does what it wants, only occasionally — out of benevolence — letting a weather forecast be accurate.

We bounce in and out of sunlight and dodge rain showers, driving down Hwy 205, snaking our way around the south end of Steens Mountain, until we hit Fields — a tiny community that includes a one-room school house, a few homes and the Fields Station and Cafe. An old stage stop, it still serves the same purpose, only to cars instead of wagons. The town is so remote that pilots sometimes land small airplanes on the highway, then taxi up to the station’s gasoline pumps and refuel before ordering lunch.

It’s a slow Saturday when we walk in to order our own lunch at the cafe (famous for their burgers and giant milkshakes), where we meet Thaddeus Downs. He’s a charming eighth grader with curly blond hair, braces and a youthful sense of humor, cracking jokes and asking about our day as he takes our order from behind the cash register.

In the fall, Downs will be a high school freshman. He says his family moved to Fields 10 years ago. Although he is going to the Fields elementary school now (one teacher, four students), next year he will live in the dorms during the week, attending the school in Crane.

He says he’s excited to try living away from home. He’s unsure if he can pick his roommate, but says he has several friends already attending the school.

“I’ve already got some stuff picked out for my dorm,” he says.

When asked what things he’s looking forward to, he says he’s excited about the different types of classes he can take there — a notable difference from the small school house local kids attend, across the highway from the cafe

“I’m excited for the weightlifting room,” Downs adds, smiling. “And sports. I play basketball.”

After taking a stroll around the Fields (it doesn’t take long), we return to fill up on gas. Downs makes a few more jokes as I pay. I wish him well and get back into the car.

We continue our drive around the East Steens Loop road back towards Crane — Downs’ future school commute. The drive takes us past the eastern flank of the mountain, showcasing its dramatic, rugged peaks and snow topped ridges. On the two sides of Steens, the Catlow Valley stretches out to the west for miles, with the alkali-white Alvord Desert to the east. It’s a spectacular sight, especially this time of year with the yellow and purple wildflowers coming into bloom among the sagebrush.

Eventually, we make it back to Crane and stop once again at the big white sign on the edge of the road leading into town that says “Welcome to Crane: Home of the Mustangs, a proud community that stands together.” The area is quiet, almost void of movement.

From Fields to Crane we’ve driven 102 miles — 44 of them on a gravel road. Come Sunday evening, the students and many teachers will settle back into the school campus, and the small community of Crane will be filled with the lively buzz of school once again.