When Frank Herbert wrote Dune he was a newspaper reporter in Florence, Oregon. The stark sand world that inspired his sci-fi classic is still orbiting the central Oregon Coast. Even without the physically impossible sand worms that Herbert dreamed up, the Oregon Dunes are inspiringly alien.

First-time visitors often sample the sand at Honeyman State Park or Tahkenitch Creek. Newbie thrill seekers might rent a dune buggy or a sand board. When you’re ready to go big, however, hike to the tallest dunes of all — the trackless Sahara of the Umpqua Dunes.

No off-road vehicles disturb the immense quiet here. Although the hike from Eel Creek to the beach begins and ends on marked paths, most of the 2.7-mile route crosses a stark, trackless dunescape of wind-rippled sand.

If you don’t have a Forest Service parking pass for your car, stop in Reedsport to buy one at the Oregon Dunes information center where Highway 38 meets Highway 101. Then drive Highway 101 south of town 11 miles. Beyond the Eel Creek Campground 0.2 miles — between mileposts 122 and 123 — turn right into the John Dellenback Trailhead. Dellenback was the U.S. congressman who played a key role in designating the Oregon Dunes as a National Recreation Area. Today his daughter Barbara Dellenback is a familiar voice on KLCC.

The trail to the dunes starts at a signboard on the right, crosses Eel Creek on an 80-foot bridge, and launches into a Douglas-fir forest with evergreen huckleberries and 30-foot-tall rhododendrons.

This is actually an ancient sand dune, overgrown with woods. Ignore a side trail to the left (the return of an easy one-mile loop option). Then cross a paved campground road at the 0.3-mile mark and continue 0.2 miles up into the woods to the start of open dunes.

For the easy loop back to your car, keep left across the sand 200 feet to find the return trail through the woods. If you’re headed for the ocean beach, however, the only markers guiding the way are infrequent, blue-banded posts.

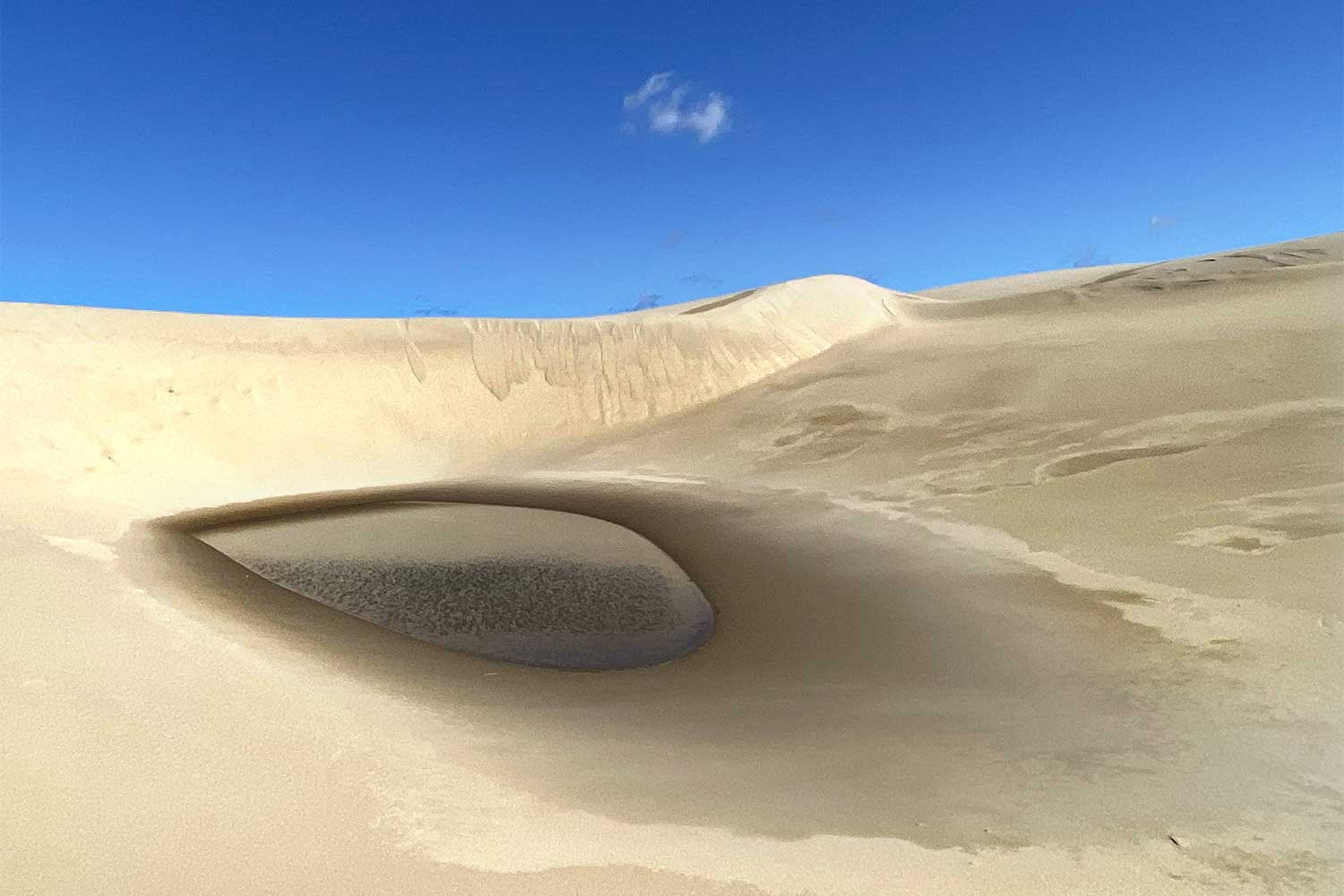

A good choice is to simply climb the long tall dune in front of you. This is an oblique dune, named because it forms at an angle to the wind. Constantly moving, oblique dunes can be hundreds of feet tall and over a mile long. The sandy troughs on either side of this one have beachgrass, dwarf blue lupine, and an occasional marshy pool.

Follow the long dune’s crest nearly a mile toward a tree island — a forested hill bypassed by the shifting sand. Skirt the tree island’s right-hand edge and continue straight half a mile to a hiker-symbol sign at the line of trees marking the edge of the deflation plain. Winds off the ocean have stripped this plain down to wet sand, allowing grass, shrubs and trees to sprout.

In summer you can follow the sign’s arrow to the right along the tree line for 0.2 miles and then turn left at another sign for 0.5 miles through the woods to the ocean beach.

This time of year, however, the entire deflation plain is a marshy lake extending everywhere into the woods and dunes. Theoretically, you could wade through this cold lake for half a mile, perhaps with hip waders, to reach the beach. Realistically, you’re going to turn back here.

Before you get mad at me for leading you on a hike that does not reach the ocean, let me explain. The beach is OK, but it’s just a beach. The dunes are the main event here — and they’re actually more interesting to explore in spring, when they’re dotted with surprising ponds. Rainwater seeps out of the sand, eroding sinuous hollows. The dunes retaliate by burying ponds, forests and trail posts.

If you’re still sour about missing out on the beach, climb one of the dunes. From the top you’ll see a blue horizon with white surf. On a clear day, look for the long shoulder of Cape Arago jutting out to sea to the south.

Is it possible to get lost? Yes, but you can always hear the roar of the ocean to the west. Your car is in the opposite direction. The big tree island is another good landmark. From there, if you head directly away from the ocean toward a distant water tank on a forested hill far inland, you should start seeing footprints leading to the Dellenback Trailhead.

And if that doesn’t work, simply stomp on the sand three times. With any luck, one of Herbert’s giant sand worms will give you a lift to your spaceship.

William L. Sullivan is the author of 23 books, including The Ship In The Woods and the updated 100 Hikes Series For Oregon. Learn more at OregonHiking.com.