When Eugene lawyer Roger Saydack was growing up in Detroit, Michigan, his father made it a point to regularly take him and his sister to visit the Detroit Institute of Arts Museum.

On one of those visits, the 12-year-old boy found himself standing in front of a painting called, simply, “The Fisherman,” done around the beginning of the 20th century by an American artist named Clayton S. Price. The 34×42-inch oil painting, done in a loose, expressionistic style, shows a single figure, centered Wes Anderson-style in the frame. The man is wearing a robe, standing in a small boat, holding his hands out and looking directly at the viewer. Overall, the painting has a mythical, even Biblical feel.

“It stopped me in my tracks,” Saydack recalls six decades later. “I was just fascinated by it. This person was talking to me. The whole setting of the painting was mysterious.”

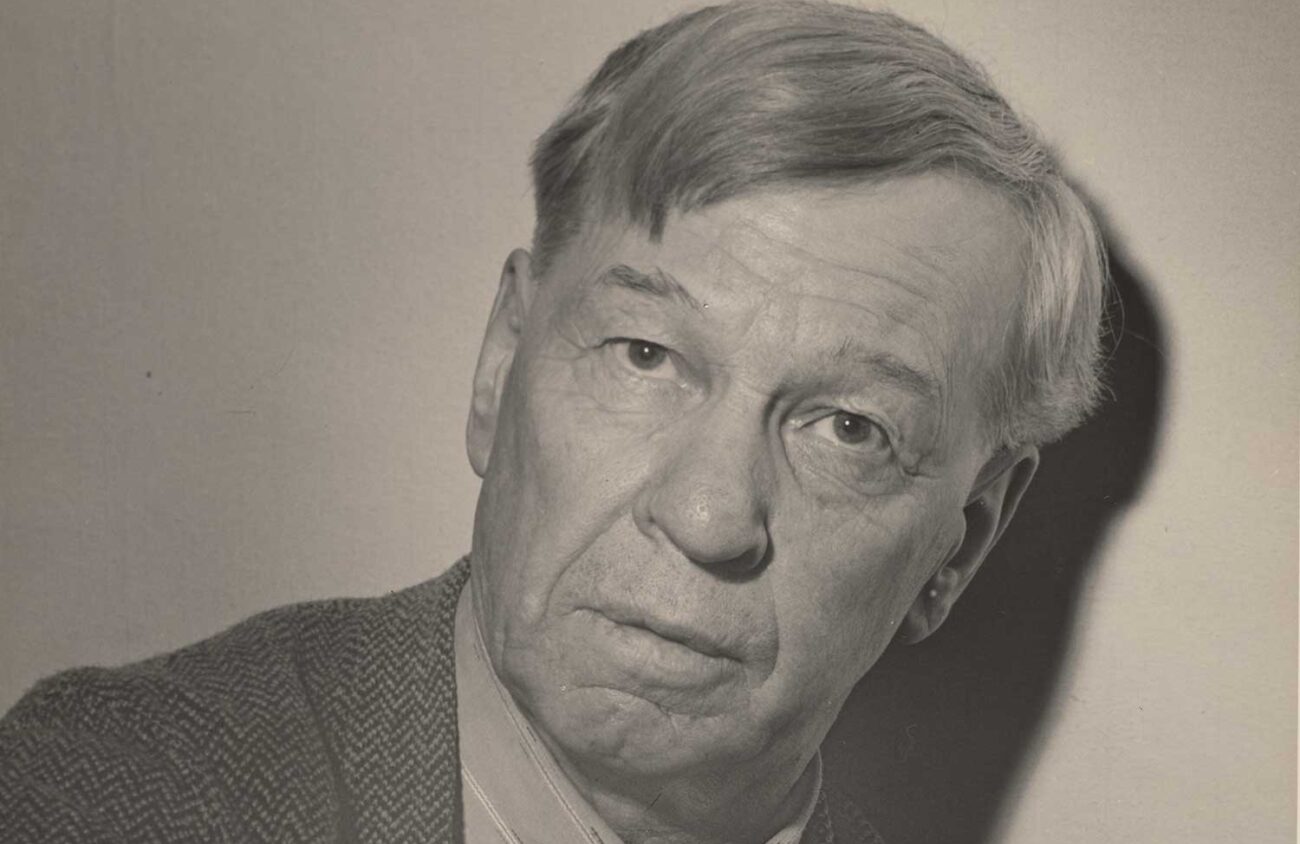

Today, it would be fair to say that Saydack is the world’s authority on C.S. Price, an artist who started life as a farm worker and cowboy in Wyoming and around the West and would go on to become a key figure in Oregon art history. In June, C.S. Price: A Portrait, Saydack’s 312-page, richly illustrated biography of Price, will be released by Oregon State University Press, and the Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Salem will open a major exhibition of Price’s paintings, drawings and other work.

The book and exhibition mark the culmination of a decades-long quest by Saydack to understand and explain the work of a never-quite-famous Oregon artist who died in 1950.

Saydack, a quiet, reflective man, never stopped thinking about Price as he grew up and majored in philosophy and minored in art at Oakland University in Michigan, where his professors talked about Price and his work.

For a time, Saydack aspired to be an artist himself, but he found working all day and painting at night to be too difficult. “I was exhausted all the time,” he says. “But that’s a decision that Price ran into, the challenge of becoming an artist. Art is not a part-time job. It’s a full-time job. It’s not something you do on the side. And he didn’t know how to manage that.” For his part, Saydack became a successful lawyer and steady patron of the arts — and a lifelong student of Price and his work.

As Saydack tells it, Clayton Sumner Price was born in Iowa in 1874, the eldest of 10 children, and grew up on farms and ranches around the West, often entertaining himself and his friends with sketches and paintings in the style of work by big-name Western artists such as Charles Russell. His artistic skills were supported by his mother, who bought him art supplies and encouraged his work, which she thought would help him express his deep feelings that “one big thing” united people, animals and all of creation.

Financed by a loan from a local rancher, Price studied painting at the St. Louis Museum School of Fine Arts for a year — his only formal training in art — and then moved to Portland, where he supported himself doing illustrations of cowboys and wildlife for Western pulp fiction magazines.

In 1915 a Price painting of a cattle drive was included in the Panama Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco, where the young painter, for the first time, saw work by post-Impressionist Paul Cezanne, expanding his notions of what painting could be about.

Another major change in Price’s life came a few years later, when he moved to Monterey, California, joining the artist colony there. Surrounded by other artists, he moved away from illustration and toward more expressive work. “His paintings transformed radically,” Saydack says. “And he became a well-known painter.”

His work can be seen today in Oregon at Timberline Lodge, Multnomah County Library, Pendleton High School and the Portland Art Museum, which gave him a retrospective show in 1942.

In 1946 he was shown at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in a show titled Fourteen Americans, which also included such better known artists as Mark Tobey, Arshile Gorky and Robert Motherwell.

Price’s paintings are in the collections of such institutions as the Seattle Art Museum, the Brooklyn Art Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art and Detroit Art Institute, where Saydack saw “The Fisherman” in his youth.

When it first opened in 1998, Oregon’s Hallie Ford Museum of Art had nothing by Price in its collection, despite its strong focus on Northwest painting. “We had works by Charles Heaney and we had works by Carl Hall, you know — Constance Fowler, George Johanson, Louis Bunce, other Oregon luminaries,” says John Olbrantz, the museum’s executive director. “But we didn’t have any work by C.S. Price.”

In 2005, Price’s niece, Frances Price Cook, donated a number of his works to the museum, including both drawings and paintings. A Portland collector also donated several of his paintings at about the same time.

“Suddenly, we went from having zero C.S. Prices to having probably 10 or 12,” Olbrantz says. “We’ve got a couple of really nice pieces. A landscape called ‘The Dark River.’ And we’ve got another sort of abstracted mountainscape. And we’ve got a couple of early drawings by him. And we’ve got a still life by him. So we have some very nice pieces, and these will be in the exhibition.”

The Hallie Ford exhibition will also include works on loan from the Met and the Brooklyn Museum, from the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon, from the Addison Gallery of Art at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, from the University of North Carolina Museum of Art and the Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery at the University of Nebraska, as well as eight paintings from the Schnitzer Foundation in Portland.

The Hallie Ford show will also include three or four cases of related objects from Price’s life. “One really cool piece of ephemera that we’re going to feature in the exhibition is C.S. Price’s drawing table and his palette,” Olbrantz says. “He left his drawing table and his palette to Charles Heaney, and when Heaney died in 1979 or 1980, the drawing table and the palette ended up at the Oregon Historical Society. So we’re going to have that.”

The exhibition will include animal figures Price carved to use as models for his work, and a dollhouse-sized barn they were kept in. The museum also owns a hobby horse Price carved for Cook when his niece was a little girl. “Well, we haven’t decided yet if we’re going to include the hobby horse or not,” Olbrantz says.

Price created about 300 paintings during his career, says Saydack, who has traveled the country to track them down. About 60 of those, he says, have been lost; another 60 are in private collections and have never been shown. Saydack himself has seen more than 100 of Price’s paintings in person.

While he was working on the book, Saydack had a dream about meeting Price in person. “Everything you need to know about me is in those paintings,” the artist told him. “It’s all on these walls. Everything.”

C. S. Price: A Portrait opens with a reception 6 pm June 14 and runs through August 30 at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art at Willamette University in Salem. Roger Saydack’s biography of Price, with the same title, will be available from OSU Press; Saydack will give a talk about Price at the gallery at 5 pm June 21.