All photos by Todd Cooper. See the whole gallery here

Well, I was totally wrong about that first song.

But first, Rain Machine, who blazed through their stoner hippie rock jam (this is a direct quote from my scribbled-in-the-dark notes, but I don’t know whether I just wrote it down or Kyp Malone said it; I suspect the former). They ended with a song that references castration fear and — I’m pretty sure — involves Malone repeating “FUCK ALL” at length. That takes balls, folks. Malone noted that it’s hard to play a stand-up show to a sitting-down crowd, but the band was pulled it off with mellow aplomb. Malone’s the guitarist and one of the singers of TV on the Radio, but Rain Machine songs take up space in an entirely different way. The structures are different, the feeling more twisty and internal. And in the Hult Center, these weird, personal-but-sprawling songs sounded fantastic.

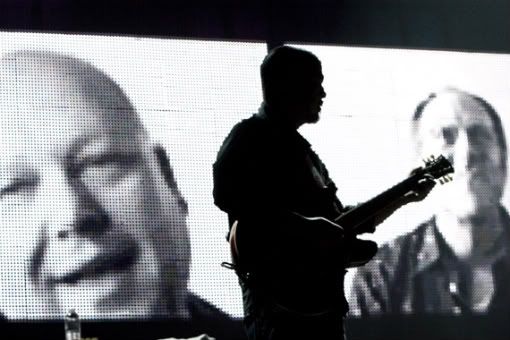

The band’s intro involved a shit-ton of fake smoke and a scratchy old film showing on the screen behind the stage. People oohed audibly when the images on the screen split into three, four, more individual pictures, but they stood up in unison when the band appeared. “B-SIDES!” Kim Deal yelled from her position just out of the spotlight. “MORE B-SIDES!” Eventually, “More b-sides! I’m sure you guys haven’t heard of them. They’re so rare we had to learn them.” I’m not a collector; I didn’t know them. No one seemed to care either way. The front row wiggled and swayed. The balcony stayed seated, at least for the time being. The angle’s a bit extreme up there.

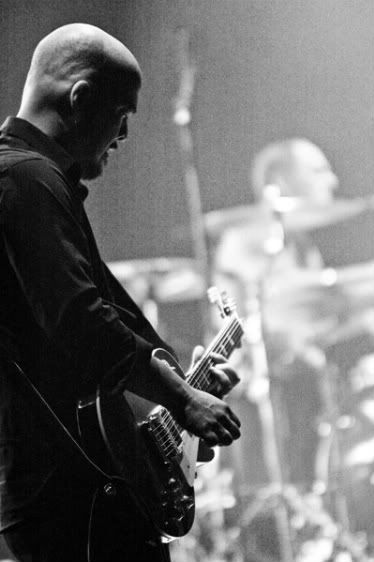

You know all these songs. I got goosebumps as Deal’s bored vocals, still the epitome of a distant, clear style that people keep trying and failing to copy, drifted above Black Francis’ growl (she kept referring to him as Charles, but I feel obliged to use his Pixies name). After every song, the cheering was so loud I had to plug my ears; during every song, Joey Santiago’s guitar cut through everything, piercing and precise. This wasn’t like the last Pixies show in Eugene, which left me underenthused and underwhelmed. This felt a little bit more like the echo of a Moment, a flashback that let those of us who never properly appreciated the Pixies — or were just too young, too behind, too dense to get it then — have a glimpse of how it might’ve been when Doolittle appeared in 1989.

For the album’s finale — “Gouge Away,” if you’ve forgotten — the screens behind the band reflected the crowd, in blurry, ragged slow-motion. After the last note, the band left the stage, shaking hands and waving; the screens changed, showing the four of them waving, bowing, laughing. “It’s meta and kind of awesome,” I scribbled in the dark as the stage cleared and the frantic clapping and stomping for an encore ensued.

(I don’t recommend being in the balcony when the Hult is full of stomping Pixies fans. It’s like Mac Court, but scarier somehow.)

Yes: The “U.K. Surf” version of “Wave of Mutilation” — the one from that cassette soundtrack I had all those years ago. I was of two minds about this: Yay, two versions of a song I love! and Hey, are you serious? Two versions of one song? No one seemed to mind. Smoke smothered the stage amusingly, if literally, for “Into the White.” For the second encore, the house lights stayed up the entire time. I forgot about watching the band and watched the audience, who unselfconsciously sang every word of “Gigantic,” at the end of which Deal executed a tiny curtsey. Two more songs (“You are the son of a motherfucker” is likely not a phrase that’s been said from the Silva stage before), and then —

Was there ever any chance they’d end with anything but “Where Is My Mind?” When you have a song like that, with that perfect Pixies dynamic, that echoey, eerie Deal vocal, can you end on any other note? You can’t. Even if half of us can’t help but think of the end of Fight Club when we hear it, you still don’t have any other option. You have to let that song ring and settle and sink, with all its resignation and tricky beauty.

Women in the balcony blew kisses to Kim Deal and the audience on the main floor all but rushed the stage, hands outstretched, when it was over.

Doolittle is 20 years old and crazy influential. But it’s ageless. And it, like every Pixies album, is a particular example of the magic of chemistry: You can like the Breeders all you like, you can love Grand Duchy, you can even have a fondness for Cracker. It doesn’t matter: The Pixies are more than the sum of their parts.