Behind every great writer hides an asshole. Dostoyevsky was a religious freak with a gambling problem. William Burroughs plinked a slug through his wife’s forehead. Faulkner guzzled a half-gallon of rye every day before noon. Shakespeare only willed his wife the spare bed.

I’m far from a great writer, but I sure can be an asshole sometimes. It’s true. Maybe you should stop reading this.

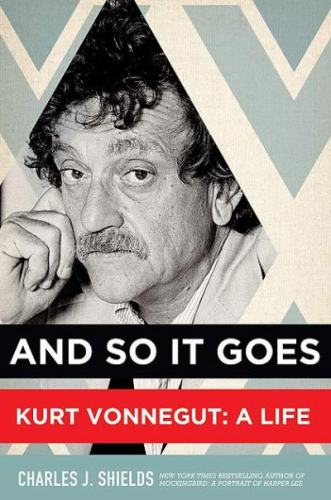

Listen: Charles J. Shields has come unglued by loathing. Among his other nebulous pastimes, Shields is a biographer, and his latest subject is the late American countercultural writer Kurt Vonnegut, author of some 20-plus works of fiction and non-fiction. Shields’ book, And So It Goes — Kurt Vonnegut: A Life (Henry Holt & Co.; $30), derives its title from the fatalistic, cosmically sad refrain Vonnegut employs throughout his 1969 masterpiece Slaughterhouse-5.

A self-declared atheist, pacifist, feminist, humanist and chain-smoker of Pall Malls, Vonnegut is an oddly divisive figure: Adored by millions of fans and writers, he nonetheless draws ire from critics who believe his brand of absurdist, dystopic satire is best relegated to the genres of science fiction and young adult reading.

The first half of Shields’ bio depicts Vonnegut’s early life and burgeoning career, leading up to the publication of Slaughterhouse-5. The writing is swift and engaging, and Shields — with almost unlimited access to Vonnegut’s archives — paints a lively picture of Vonnegut’s family life during the Great Depression and his devastating experiences as a solider in World War II. All of this background makes for fascinating reading. Then something goes sour.

A writer’s literary tone is difficult to parse, but were I to take a shot at deciphering Shields’ character from his words, I might say something like this: Charles Shields exhibits the kind of shocked disenchantment and psychological burn-out suffered by many wrongheaded biographers who appear constitutionally unprepared to confront the all-too-human foils of their subjects. Shields just doesn’t have the stomach for this kind of work; he is too anal and earnest and pie-eyed. For instance, he seems dismayed to discover that Vonnegut was given to occasional fits of anger, envy and obtuseness, emotions that Shields almost invariably labels “immature.”

At some point, the biographer’s disappointment curdles into rancor, and he can scarcely conceal his disgust for Vonnegut’s professional jealousies, his remoteness as a parent, his ideological hypocrisies. As Shields unearths every venal sin and ethical hiccup, his writing grows shrill, nit-picky and condescending, sort of like a hall monitor on a grade-A power trip. But in correcting one error, a fool often rushes into its opposite, and Shields, a man once under the thrall of Vonnegut’s writing, obviously feels it is his duty to call out the real Kurt Vonnegut.

He becomes trite and wheedling, and prone to error. For instance, Shields notes that Vonnegut, an avowed socialist, once sampled caviar on first-class flight (gasp!), but then relegates to a footnote the fact that Vonnegut donated to a “rescue fund” for Richard Yates and, further, that he organized another fund to pay for the medical bills of paralyzed author Andre Dubus. Shields says that Vonnegut’s famous “chalk talk” was published in A Man Without a Country, when in fact it first appeared nearly a quarter century earlier in Palm Sunday.

It’s difficult to say exactly where Shields jumps the shark. Whatever the specific moment, by the conclusion of his biography the poor man has completely succumbed to the kind of apoplectic outrage one witnesses in children not getting their way. Am I calling Shields immature? Maybe. More precisely, he seems the sort of reductive Manichean who needs to believe in the catholic purity of immaculate heroes living in an unambiguous universe of good vs. evil.

And here I yield the floor to Vonnegut himself, and bow out: “I am not pure,” Vonnegut said at a 1973 rededication Wheaton College Library. “We are not pure. Our nation is not pure. And I insist that at the core of the American tragedy … is the illusion engendered by World War Two: that in the war between good and evil we are always, perfectly naturally, on the side of good. This is what makes us so unrestrained in the uses of weaponry.”