Paying Attention

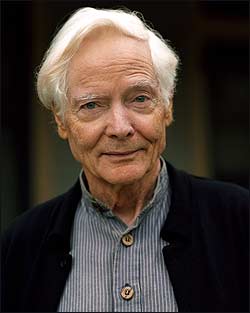

Poet W.S. Merwin says what can’t be said

by Cecelia Hagen

|

“Poetry always comes out of what you don’t know,” says William Stanley Merwin, one of the great poets of our age. He writes by sitting in front of a piece of scrap paper (“a nice new sheet of white paper” would be too intimidating, he says) and waiting for something to surprise him.

Although Merwin feels that “poetry’s about what can’t be said,” he has written more than 20 books of poems and eight books of prose, and translated work from an astonishing array of languages. Clearly, what can’t be said is worth pursuing.

Born in 1927 in Union City, Pa., Merwin was the son of a Presbyterian minister, and his first poems were hymns. He entered Princeton at age 16 and studied with John Berryman, then tutored Robert Graves’ son for a summer in Mallorca. While still a teenager, Merwin sought the advice of Ezra Pound, who told the young poet he should learn another language and begin to translate poetry so that he could learn the possibilities of English.

W.H. Auden selected Merwin’s first book, The Mask of Janus, as the Yale Younger Poets award winner in 1952. Publishing a book every two or three years, Merwin progressed from an early formalism into more experimental, colloquial language. The Lice (1967) and the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Carrier of Ladders (1971) reflect his opposition to the war in Vietnam and give voice to his growing sense of the pervasiveness of loss. “If I were not human I would not be ashamed of anything” (from “Looking for Mushrooms at Sunrise”). That poem goes on: “Where they appear it seems I have been before / I recognize their haunts as though remembering / Another life // Where else am I walking even now / Looking for me”

His interest in Buddhism and the natural world infuse his work. Migration: New and Selected Poems (2005) received the National Book Award, and his most recent, The Shadow of Sirius (2008), won him his second Pulitzer. One reviewer has compared Merwin’s later work to Matisse’s, writing that “Merwin has given to 21st-century poetry what Matisse gave to 20th-century painting with his late-in-life paper cutouts: the irreducible essence of his art.” The late poems have the rapid tumble of nature, spilling down the page in unpunctuated, run-on lines that create a level of energy and tension that end-stopped lines do not.

For Merwin, poetry is “a way of paying attention,“ and he feels that attention is based on pleasure. “Poetry always begins and ends with listening,” he says. “You listen for something only you can hear.” He has asked that his reading start with a question-and-answer session and end with poetry, so he can leave the audience with the sound of poetry in the air. “When you hear it,” he says, “it enters you at a place that is deeper than interpretation.”

Since 1975 Merwin and his wife, Paula, have lived in Hawaii, where they work to restore their land — once a pineapple plantation — to its native state. Making a forest is easier said than done, he admits: “I don’t really know what I’m doing, but I do it anyway.”

W.S. Merwin speaks at 2 pm Sunday, Feb. 7, at the Eugene Public Library. Free.