Life After Death

Science, race, emotion and The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

by suzi steffen

Nonfiction writing, good nonfiction writing, takes serious time. But Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (Crown, $26), which finally went to press at least 10 years after the writer began her serious research, shows how very well that time can pay off.

|

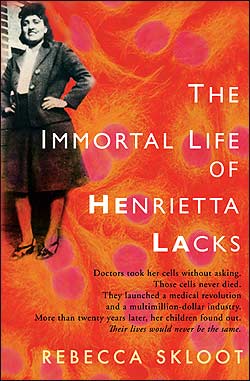

The book sits in the second position on The New York Times bestseller list as I write this, and though it should probably be sitting in the top spot, it’s somewhat of a miracle that the book (which has a truly terrible cover) should be on the list at all. A science story about the cancer cells of a poor African-American woman from Baltimore? A tale that went through several tellings, a BBC documentary and a crazy lawsuit or two?

But in the same country where a frighteningly large percentage of people don’t even believe in evolution, this story still has the power to capture attention and admiration. The book combines several strands. One is the tale of a large institution taking cells from a patient who didn’t give her consent and those cells’ unbelievable power to serve as basically the biggest story in biology, virology and DNA sequencing for the past 50 years. Another concerns the criminally unfair difference between those using and selling the HeLa cells of Henrietta Lacks and the Lacks family’s poverty and uninsured status. Finally, there’s the story of Rebecca Skloot, a young white woman at the beginning of the research, financing this book with student loans and credit cards, determined to persist through the Lacks family’s justifiable suspicions, taking them on the journey as she uncovers layer after layer.

Of course, all of those strands weave into the ugly tapestry of racism. From the story of Henrietta Lacks’ daughter Elsie, institutionalized and deeply abused by a system that regarded African Americans, long into the 20th century, as something like cattle, to the clueless ways scientists interacted with the Lacks family, and to the “white Lacks” acting like they don’t understand how they’re related to “the colored Lacks” (perhaps they need to read a bit about the history of slavery?), Skloot recounts stories that run the gamut of racism. That racism (and classism) hits every note: banal, institutional, personal, all of it affecting the way that Henrietta Lacks was treated in life and the way her family was treated after her death even as Johns Hopkins and biomedical companies all over the world benefitted from her cells. Skloot’s portraits of Lacks’ children, especially Deborah, give them a full measure of humanity and show how much they lost as the world gained from their mother’s cells.

We likely wouldn’t have a polio vaccination without the HeLa cells, which could live and prosper outside of Lacks’ body. All kinds of medical research and cell-level research would never have been completed without Lacks. But I don’t want to reveal too much of the story: The marvel in this book lies not only in the narrative but in how the narrative is written and constructed, how science and religion can mesh and entangle, how redemption can arrive suddenly in a harshly lit sterile basement as people lean over a microscope.

Skloot takes responsibility for her privilege as a middle-class white woman (the daughter of another famous literary nonfiction writer to boot); she’s giving a portion of the profit from the book to the children of the Lacks family, who have so long been exploited for the gain of others.

She also specifically addresses informed consent and how our tissues can be taken, used and sold and reconstituted and tested and whatever a large, often for-profit industry wants to do, without any legal recourse for us. Henrietta Lacks was done wrong before her death from cervical cancer, and so might almost any of us be now. Thanks to Skloot’s persistence and clarity, however, that chance may diminish.

Rebecca Skloot reads from The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks 2pm Sunday, April 18, at the Eugene Public Library and 6 pm Monday, April 19, in 150 Columbia Hall on the UO Campus.