Folkie Madness

Strumming through centuries of British music

By Brit McGinnis

|

In our neck of the woods, folk music is often taken for granted. The Randall V. Mills Archives at the UO is one of the biggest resources for folklore in the Pacific Northwest. Guitar and banjo players mark every corner. Northwestern-toned blues albums seem to be released every week, for Petes sake.

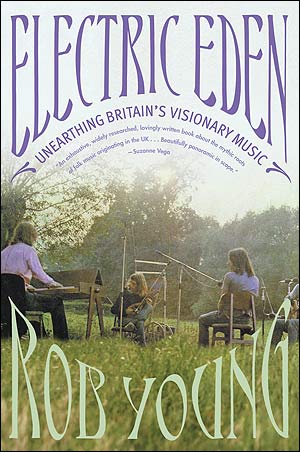

But Rob Youngs book Electric Eden: Unearthing Britains Visionary Music explores the roots of another major site of folk music history ã the United Kingdom. More than the Stones and The Beatles originated in this merry old kingdom; think LPs of medieval flute ensembles, opera cycles recounting the legend of King Arthur and psychedelic remixes of John Donne poetry.

With a steady storytellers voice, Young describes the history of folk music in England. Readers will be thrilled by the height and depth of Youngs storytelling. We remember that this is the land of Shakespeare, Thomas Hardy, The Wind in the Willows and The Canterbury Tales. The sheer scope of Youngs research is incredible, spanning centuries of music.

The eclectic history of folk music, with all the historical elements that go along with its development, is embraced in full by Young. We learn about the influence of McCarthyism and the impact of the invention of the 33 rpm record on the folklore-collecting community. After all, when you can record up to 40 minutes of music at a time, you dont need to make someone shut up after the fifth verse of whatever ancient verse theyre singing for your benefit.

Young portrays the heroes of folk music, even the most eccentric, with a sympathetic and validating voice. Imagine someone being so obsessed with the tunes your dad whistles that he asks him for the lyrics, on occasions months apart, so he can distinguish the changes happening over time. Thats Cecil Sharp, one of the first people to fully record on paper English folk music lyrics. Hes famous in folk history (and a little crazy), and is made a hero in Eden.

Whats absolutely amazing about this book are all the parallels one could draw between the folk music revival of England as compared to that of America. The BBC radio programs As I Roved Out and Ballads and Blues appear as the British cousins of A Prairie Home Companion. Young himself sneaks in an allusion to Casey Jones, the American folk hero of the railroads, when discussing the BBCs working-folk tribute “The Ballad of John Axon.” Many American artists, such as Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie, proved to be inspirations for young Brits itching to strum out a revolution.

But perhaps the most meaningful accomplishment of Electric Eden is the discussion of what compels people to write folk songs. We dont really talk about why people sing songs about factories, fairies or pickup trucks. Young asserts that folk songs are born primarily from poverty. Think of the traveling singers of the Renaissance, the young chaps working in industrialized Britain in the 1930s, the young women and men facing a potential future of dire unemployment in the 1960s.

In fact, the overall feeling of the book is that folk music originally came about (and remained) as a way to escape hard times. Young quotes folk singer Ewan MacColl as saying, “If you have worked yourself to a standstill and still been unable to feed the kids properly, then you will know why these songs were made.”

Electric Eden is dense, slightly more than 600 pages. Its certainly not a breezy beach read, but who cares? Youngs approachable language, attention to detail and clear passion for his subject matter makes the book a delectable read. He writes like an attendee of a folk music concert, watching the artists with a critical but excited eye.