Bike Planning

A new bike system could mean a big jump in cycling

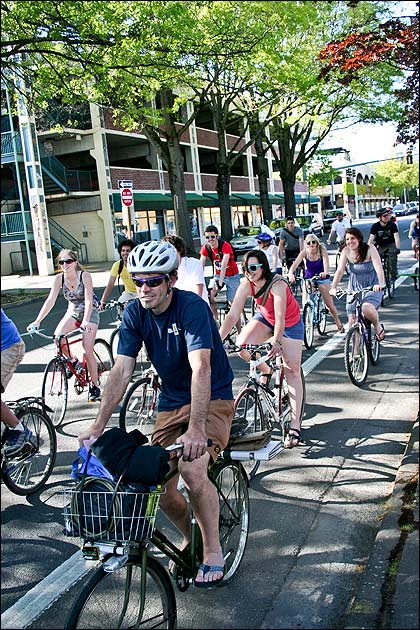

story & photo by Alan Pittman

Portland hatched a plan this year to quadruple the share of people biking and create “a clean, thriving city where bicycling is a main pillar of the transportation system and more than a quarter of all trips are made on bicycles.” Can Eugene do the same?

Using one of the lead consultants that worked on the Portland plan, Eugene kicked off a project this week to create an ambitious new bike and pedestrian transportation plan.

|

| Hundreds of bikes paraded downtown as part of the May 8 Bike Music Festival |

“It’s a pretty exciting time to be working on this,” said city bike planner David Roth, citing a potential big boost in federal funding and increased local bike activism.

“I’m very excited,” said Shane Rhodes, manager of the Eugene Safe Routes to Schools program. “If we build a good solid plan and funding to back it up, then we’ll be on a much better path.”

Roth said he’ll take project consultants, including Alta Planning of Portland, on a bike tour this week of Eugene. The city has $149,000 in a grant through ODOT of federal money for the planning work. The project will go public in the fall with a citizen advisory committee, public meetings and website with interactive map to propose improvements. Roth said he expects a completed plan approved by the City Council in about 18 months.

According to the Portland plan, increased biking can transform a city with a host of benefits, including: safer streets, less obesity, less traffic congestion, less global warming, less toxic air pollution, less water pollution, less taxes, less car costs, less crime and a more neighborly, livable, fun and vibrant city. Biking also boosts the economy and jobs through tourism, property value increases, local bike industry, increasing local spending and attracting the “creative class” that’s key to business growth, according to Portland’s 2030 plan.

About 8 percent of commuters in Eugene bike, according to the U.S. Census. Roth said the Eugene plan could include a mode share goal as ambitious as Portland’s 25 percent.

Eugene is one of the top cities in the nation for biking, but the cycling percentage here has not increased since a high point in the 1970s, according to Census numbers.

However, unscientific bike counts at 17 locations last year by the city, showed a 26 percent increase over the year before. “I think it’s on the rise again,” Roth said of biking. “It’s turning into the cool thing to do.”

Portland surveys found that about half of its residents would be interested in biking but don’t for safety concerns. Planners there focused on making a wider range of people feel more safe and comfortable cycling by offering hundreds of miles of new bike boulevards, bike lanes, separated on-street “cycletracks” and off-street bike paths.

A city of Eugene “statement of work” for the planning contractor appears to emphasize bike boulevards over bike lanes. “The city has already completed bike lanes in most locations where they are feasible,” the document states.

The best bike boulevards have pavement painted with large “sharrows,” traffic calming and cyclists sharing road space with cars on low traffic streets, according to the Portland plan.

But emphasizing bike boulevards over bike lanes has been controversial in some cities. If the design does not reduce through car traffic with cyclist-only diverters, many bikers may not feel safer. Also, if the road is already low traffic and safe for cyclists, the official “bike boulevard” designation may not offer much improvement. If the bike boulevard is low traffic because it doesn’t go to the commercial areas where cyclists want to go, it also has less to offer.

“I think bike boulevards are pretty cool,” said Paul Moore, owner of the new Arriving by Bike cycle commuting store. But he said they should be part of a network that includes bike lanes on busier commercial and residential streets. “What I wouldn’t want is bike boulevards to be the end-all solution,” he said. “They don’t really get you where you want to go.”

Moore said he’d like to see the city convert south Willamette Street in front of his store to two lanes with a center turn lane, widened sidewalks and bike lanes. “The situation out here is horrible for cycling.”

Cities in Europe have found bike boulevards less useful and instead focused on separated cycletracks protected by low curbs, parked cars and/or medians to achieve bike mode shares up to 50 percent.

“Optimally, cycletracks are the best,” said Jim Wilcox, director of the BikeLane Coalition.

But cycletracks can cost much more than bike boulevards; Portland estimated as much as six times more per mile. But they didn’t do an estimate of cost per added cyclist.

Cost may be the biggest obstacle to keeping Eugene’s bike plan from gathering dust on a shelf.

The city has not dedicated a regular source of funding for new bike infrastructure and relies instead on occasional federal and state grants, according to Roth.

Lately, the city has been reducing rather than increasing bike funding. The City Council voted two months ago to divert almost all of the limited amount of flexible federal transportation money (STP-U) it could get to road repairs rather than bike and pedestrian safety projects. The city’s Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee (BPAC) joined the Sustainability Commission in calling for the city to spend all of the several million dollars a year on non-car projects. The city manager’s proposed budget also cut $153,000 from bike path maintenance.

The current regional TransPlan devoted about a billion dollars to cars over 20 years with only about 1 percent of its funding for bikes. The plan included a slight decrease in bike mode share while the region devoted hundreds of millions of dollars to freeway interchanges and bridges. A recent plan update (RTP) spurred a 13 percent increase in driving per capita with a half billion dollars in added capacity to Beltline and other freeways.

The local share of bike funding should increase at least ten-fold, Wilcox said. All the money spent on more and more car projects makes it hard for bikes to compete and is counterproductive, he said. “When we build more infrastructure, we have more people driving, so we build more infrastructure, so we have more people driving.”

Roth said the new Eugene plan will examine possible ways to increase bike funding. U.S. Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood recently announced a “sea change” in federal funding to “treat walking and bicycling as equals with other transportation modes.” Congressman Peter DeFazio could help Eugene win some of that new funding as chair of the key House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure.

But even if Eugene had the money, it may lack the political oomph for a bike transformation.

In the 1990s, Eugene had a mayor and three city councilors who regularly cycled to meetings. But now, they all arrive by car. “You don’t have anyone there that’s an advocate,” Moore said.

Right now, the council is spending most of its time working on a plan that appears likely to expand the city’s urban growth boundary to allow more sprawl.

BPAC chairwoman Jennifer Smith called the city’s growth plans “ridiculous” at a meeting last week. She said, “if it becomes more difficult to drive, people will live more compactly. … The widening of Beltline doesn’t serve that option or the climate policy.”

Roth said the formation of the GEARs bike advocacy group has increased cyclist clout. “Now they’re a pretty big player in how things are done locally.”

But Moore said he’s concerned that GEARs, which formed when a bike advocacy group merged with a recreational riding group, has a diluted mission and less focus on bike advocacy. “We don’t have an advocacy group like the BTA,” he said, referring to Portland’s powerful bike lobby.

Rhodes said the new plan “has the potential to really rally the troops” around bike advocacy.

Eugene’s Sustainability Commission has called for a “complete streets” policy to include bike/ped infrastructure in new projects. But many of the newer road projects the city has completed or is planning, including new roads on the EWEB riverfront project and “multi-way” boulevards on West 11th and Franklin, lack cycletracks or bike lanes. The city has also retreated from building planned bike lanes that involve removing car parking.

Moore faulted the city for not putting bike lanes on the reopened Olive Street downtown. “A mom with kids going to the library, where are they supposed to ride?”

So just how transformative will Eugene’s new bike plan really be? “I’d like to say it will be earth shattering,” said Roth. “At this point, it will be progress.”