Fashion

Fashioning Eugene Local designers bring “wearable art” to the masses

It’s in the Bag Eugene artist brings vintage charm to leather accessories

Ink for the Ages Permanent is the ultimate fashion statement

The Soul of the Whit Found fashion from the Whiteaker Block Party

Show Me Fashion show puts the icing on annual Whit extravaganza

Fashioning Eugene

Local designers bring “wearable art” to the masses

by Rick Levin

Check this: If an alien, summoned to search the cosmos for che outré shoes, lands in your backyard and politely asks you to delineate the latest fashion trend in Eugene, you might tell him — after you stop laughing soda pop out your nose — that what defines Eugene’s sense of fashion is that it has no sense of fashion. You might explain to your new interstellar friend that half this city looks to be wearing its cleanest dirty shirt, and the other half is just another colonial outpost of Gap.

|

But hold up — local designers Laura Lee Laroux and Mitra Chester might put a snag in the shag of your high-heeled ideas about fashion. These two style mavens and all-around sartorial ambassadors of cultural cool — Laroux owns Redoux Parlour, and Chester, who along with her husband Aaron, operates Deluxe and Kitsch — these women want to prove that fashion isn’t just glossy magazines and bulimic skinbags prancing New York runways in Prada.

Fashion is art and, more importantly, it might be the only art you and me and all of us hold in common. “Your fashion is sometimes the first and only interaction you have with the world,” Chester says. “Everybody participates in fashion.”

Some, like Laroux and Chester, participate more than others. Both artists, along with several of their talented cohorts, currently have clothes on display at BRING; their work featured prominently in the electrifying fashion show during the Aug. 6 Whiteaker Block Party; and, to cap it off, Chester and Laroux are producing “Full Steam Eugene,” the annual Summer in the City-sponsored free fashion show taking place Aug. 17 in Kesey Square downtown.

Working decidedly outside the mainstream and on their own terms, Chester and Laroux — along with a growing clutch of purveyors, propagators and makers of Eugene fashion — represent an entrenchedly postmodern and quietly aggressive avant garde that is turning the fashion industry inside-out to make it rightside-up. Like good doctors Frankenstein, designers like Laroux and Chester are tearing up the old and stitching it anew. And yes: It’s alive.

“It’s really hard for the little guy to survive in the fashion industry,” says Laroux, who after studying animal sciences at Clemson found herself enrolled in New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology, where she not only learned the ropes but soon found herself at the end of hers. “I swore off the fashion industry after New York,” she says, adding that the money-driven mentality, the insider gaming and the wastefulness — especially the wastefulness, of fabrics and other materials — made her “really grossed out.”

After leaving F.I.T., Laroux and some friends set up a soup kitchen in post-Katrina New Orleans, where in her spare time she began making new clothes out of stuff donated to flood survivors. “In New Orleans, it’s like something was missing,” she says of her return to design. “It’s like I had to do it to keep myself sane.”

In 2008, Laroux bought Redoux Parlour, a clothing store that doubles as a workshop and gathering place for local designers. “For me, community is the biggest thing,” she says about founding a fashion hotspot here. “Eugene is a community. There’s just this mindset of being local.”

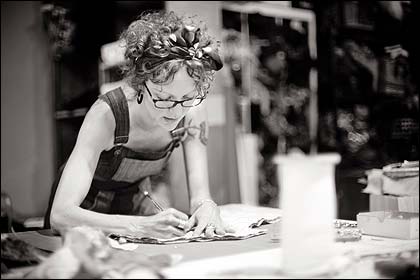

Redoux, then, is the place where Laroux makes this vision of conscientious fashion a palpable reality. On the day we visit her, she holds up a smart, simple dress made completely from men’s shirts. The dress epitomizes what she means when she talks about killing the proverbial pair of peacocks with one stone: It has utility (or recycled “wearability”) as well as appeal (its revamped style is “an expression of yourself”).

Chester’s journey into fashion was no less circuitous and globetrotting than Laroux’s, but most striking is the fact that such young, innovative designers set up camp (no pun intended) here, in the Land of Hippie. Chester, whose father works as a craftsman and whose mother, Debrah DeMirza, also designs clothing, is originally from Boulder, where she studied anthropology, philosophy and comparative religion at Colorado University.

Following a stint in Athens, Georgia — where, after redesigning a Renaissance wedding in 1999, she was exposed to the town’s cliquey fashion elite — Chester relocated (or perhaps fled) to Eugene, seeking to “foster a more positive, non-judgmental” fashion scene.

“Both of us have been disenchanted,” Chester says of her and Laroux’s experience in the maw of the fashion industry. Rather than bitterness and burnout, though, the two designers have turned those hard knocks into a kind of negative capability. “We know what we don’t like,” Chester says. “We avoid it. We’re going to do fashion wherever we are,” she adds. “We look at fashion as a medium of art.”

And like most art before the industrial revolution, fashion started as an object embedded in everyday life — a thing not to be worshipped, criticized, adored and photographed but worn on one’s body as an expression of who they are and what they do. “Our society has made it a deformation of that,” Chester says of fashion’s evolution into pure commodity. Both she and Laroux want to restore clothing to the quotidian without undermining its glamour, its everyday beauty.

Chester — who defines her bricolage style as “postmodern fashion” — calls the clothing she makes “three-dimensional wearable art,” and Laroux says that right now she is focusing on a sort of return to Depression-era simplicity, by making tasteful but sensible, affordable items like overalls and jumpsuits for all types of body sizes. “Simplicity has become a huge theme,” she says. “Just making life easier somehow.”

Working decidedly outside the mainstream and on their own terms, Chester and Laroux — along with a growing clutch of purveyors, propagators and makers of Eugene fashion — represent an entrenchedly postmodern and quietly aggressive avant garde that is turning the fashion industry inside-out to make it rightside-up. Like good doctors Frankenstein, designers like Laroux and Chester are tearing up the old and stitching it anew. And yes: It’s alive.

“It’s really hard for the little guy to survive in the fashion industry,” says Laroux, who after studying animal sciences at Clemson found herself enrolled in New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology, where she not only learned the ropes but soon found herself at the end of hers. “I swore off the fashion industry after New York,” she says, adding that the money-driven mentality, the insider gaming and the wastefulness — especially the wastefulness, of fabrics and other materials — made her “really grossed out.”

After leaving F.I.T., Laroux and some friends set up a soup kitchen in post-Katrina New Orleans, where in her spare time she began making new clothes out of stuff donated to flood survivors. “In New Orleans, it’s like something was missing,” she says of her return to design. “It’s like I had to do it to keep myself sane.”

In 2008, Laroux bought Redoux Parlour, a clothing store that doubles as a workshop and gathering place for local designers. “For me, community is the biggest thing,” she says about founding a fashion hotspot here. “Eugene is a community. There’s just this mindset of being local.”

Redoux, then, is the place where Laroux makes this vision of conscientious fashion a palpable reality. On the day we visit her, she holds up a smart, simple dress made completely from men’s shirts. The dress epitomizes what she means when she talks about killing the proverbial pair of peacocks with one stone: It has utility (or recycled “wearability”) as well as appeal (its revamped style is “an expression of yourself”).

Chester’s journey into fashion was no less circuitous and globetrotting than Laroux’s, but most striking is the fact that such young, innovative designers set up camp (no pun intended) here, in the Land of Hippie. Chester, whose father works as a craftsman and whose mother, Debrah DeMirza, also designs clothing, is originally from Boulder, where she studied anthropology, philosophy and comparative religion at Colorado University.

Following a stint in Athens, Georgia — where, after redesigning a Renaissance wedding in 1999, she was exposed to the town’s cliquey fashion elite — Chester relocated (or perhaps fled) to Eugene, seeking to “foster a more positive, non-judgmental” fashion scene.

“Both of us have been disenchanted,” Chester says of her and Laroux’s experience in the maw of the fashion industry. Rather than bitterness and burnout, though, the two designers have turned those hard knocks into a kind of negative capability. “We know what we don’t like,” Chester says. “We avoid it. We’re going to do fashion wherever we are,” she adds. “We look at fashion as a medium of art.”

And like most art before the industrial revolution, fashion started as an object embedded in everyday life — a thing not to be worshipped, criticized, adored and photographed but worn on one’s body as an expression of who they are and what they do. “Our society has made it a deformation of that,” Chester says of fashion’s evolution into pure commodity. Both she and Laroux want to restore clothing to the quotidian without undermining its glamour, its everyday beauty.

Chester — who defines her bricolage style as “postmodern fashion” — calls the clothing she makes “three-dimensional wearable art,” and Laroux says that right now she is focusing on a sort of return to Depression-era simplicity, by making tasteful but sensible, affordable items like overalls and jumpsuits for all types of body sizes. “Simplicity has become a huge theme,” she says. “Just making life easier somehow.”