The Milky Way

Small organic dairies try for bovine bliss

by Shannon Finnell

If one thing is clear from omnivores committed to eating organic, it’s that they care about the lives of the animals whose milk and meat they consume. Just look at the premise of the California Milk Advisory Board’s multi-million dollar, decade-long “Happy Cows Come From California” ad campaign (which represents both conventional and organic). “I love it here!” exclaims one cow, surrounded by rolling green pastures.

The concerns of milk and cheese lovers worried that their dairy products are ethically curdled would likely be alleviated by a visit to Jon Bansen’s family dairy farm, Double J Jerseys, south of Monmouth. Bansen learned dairy farming from his father in a small non-organic operation, but he turned more and more to organic practices in the ‘90s before joining the Organic Valley cooperative in 2000. Bansen has been turning the cows out to pasture more and more over the years, perfecting methods that resulted in his herd of about 180 Jersey cows spending about 20 hours a day outside in a system called “intensive rotational grazing.”

|

|

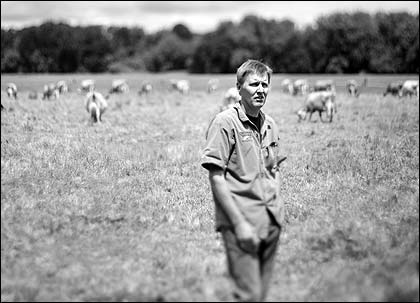

| Jon Bansen. Photos by Trask Bedortha. |

Organic hasn’t always translated to outdoor cows. Before last year, the National Organic Program’s rule mandating access to pasture was vague. This left quite the loophole in organic policy, creating a wide berth between farms that favored a lot of pasture time and others that, while free from antibiotics and hormones, minimized their cows’ time on grass.

In May 2010, Oregon’s Confined Animal Feeding Operation program levied a $20,000 fine against a Wilsonville area organic dairy that provides milk to the Pacific Village brand (sold locally at Kiva and Market of Choice) for manure-related violations. Neighbors told The Oregonian that the cows were rarely given the opportunity to graze.

A month after the record-setting fine, the National Organic Program updated its regulations on how cows get their food. Before then, organic cows and other multi-stomached, cud-chewing animals were required to have some access to pasture during the grazing season, but the level of access was unspecified. The NOP realized that consumers who favored organic animal products weren’t just concerned with limiting their intake of antibiotics and synthetic hormones; they also wanted to support a system of un-tortured, even happy cows that spent a large chunk of their lives outdoors. The organic standards needed a more specific benchmark, but those standards also had to take into account the different climates where organic dairies exist.

Ultimately, the NOP settled on these requirements: Cows must graze in pasture for the entirety of the local growing season, which must not be fewer than 120 days. That time doesn’t need to be consecutive; it can be broken up to deal with unforeseen weather events or other issues. During this time, the animals must obtain 30 percent of the dry matter in their food from pasture.

“It doesn’t sound like a lot, but you have to keep in mind that they have to eat more pounds in pasture than they would in hay,” says Callyn Kircher of Oregon Tilth, an organic advocacy and certification organization. That’s because the water content in pasture is higher than the feed the cows receive in the barn — it takes more eating to process the high-quality pasture diet.

So the access to pasture rule was updated in 2010 and, as of June 2011, all new and existing organic dairies are required to be in compliance. Smaller dairy farms that already kept their cows mostly outside didn’t have to change much about their grazing practices. The law necessitated change mostly at farms with herds too large to forage on inadequately small or unmanaged pastures.

“I would say that the vast majority were already in compliance,” Kircher says. “What’s really changed is the record keeping.”

To show that their cows meet the requirement of receiving 30 percent of their dry food from pasture, farmers must keep meticulous notes for annual inspection.

A heck of a good cow

It’s clear that the precision and attention to detail of the record keeping required for organic certification is right up the Bansens’ alley. The herd grazes in a roped-off sector of the fields for 12 hours before the cows are moved to a new area, after which the grazed field has 30 days until the cows return. The herd is managed specifically, Bansen says, to maximize the amount of grazing time and minimize the milking time, which takes place on pavement.

Even the herd’s path from pasture to parlor is designed to get the cows back to the grass as soon as possible. In total, milking the Bansens’ entire herd takes about two and a half hours, with about 15 minutes of pavement and milking time for each cow. The rest of the time, at least when weather doesn’t prevent them from being outside, the herd is on grass.

For Bansen, farming is about treating each animal as a unique living being. “I choose to make sure all the animals we deal with have respect the whole way,” Bansen says. Part of that respect is knowing each cow as an individual. Instead of numbers on their ear tags, each of Bansen’s cows has a name tag. As they wander behind him in the pasture, he can turn and recognize them, just like 180 friends he happens to see every day. “I think that’s Helen, isn’t it?” She turns, and it is. “Helen’s a heck of a good cow.”

Since going organic, Bansen has noticed a significant improvement in the quality of his milk and in his herd’s general health, though the quantity of milk yielded per cow has dropped a bit. “I’m not getting all the milk I used to,” Bansen says of the switch from conventional to pasture-intensive organic. “I’m also not buying all the grain I used to and not taking care of sick cows.”

Bansen’s farm is part of Organic Valley, a farmer-owned cooperative that includes 1,643 farms across the U.S. The dairy industry calls Organic Valley’s marketing strategy “aggressive,” and that’s probably accurate, although aggressive could also describe the conventional dairy industry itself. Organic Valley is a collection of true believers, farmers and workers united in their faith that smaller scale and organic is the only way to go.

Raising healthy cows

Guy Jodarski, a veterinarian with Organic Valley, says the average life of a conventional dairy cow is only four years. Jodarski stands with Rosie, a Bansen cow who’s now 14 years old and still milking, and credits her longer lifespan to an outdoor, high-forage life.

“This sort of lifestyle and diet is healthy for the cow, healthy for the land and healthy for the people,” Jodarski says. It’s not necessarily the fact that the cows are outside or organic that is significant to their health, he says. Making sure the pasture they’re foraging is high quality also makes a huge difference.

In many conventional dairies, the lives of cows are cut short by sickness but also because the intensity of milk production shortens the window of time a cow can produce milk. After that, they’re slaughtered.

At organic dairies, the access to pasture rule means that a more outdoor-oriented life is mandatory. Does that mean a life producing milk for humans can be happy? Jodarski thinks so. “It’s a high quality life and it’s more of a natural cow’s life,” Jodarski says. He says the annual pregnancy cycle that causes cows to lactate isn’t something unnatural that farmers have created; it mimics what’s found in the wild. “If you look at wild ruminants like deer, sheep and bison, they have an annual cycle of pregnancy,” he says.

Jodarski also says that harvesting an animal for milk can be a respectful process, citing India as a place where a major religion prohibits any disrespect of cows. “They don’t eat them, but they drink the milk,” he says.

Organic vets aren’t left without medicine just because antibiotics used by conventional dairies are not in their arsenal. “There are herbal things we use,” Jodarski says, such as aloe vera for inflammation-related problems or garlic tincture for infections.

Greener milk

Jodarski thinks that while growing concern for the welfare of animals and for more nutritious milk are part of the demand for organic dairy products, economics and the environment are also driving factors. “There are costs that no one is paying for in the other products,” he says, “pollution and stuff like that.”

The net effect of organic dairies on their environment isn’t well established. Part of this is because organic farming practices can still vary quite a bit. One consistency is that organic dairies use feed that’s also organically grown, and they can’t use pesticides or genetically modified feed.

A big point of contention for people who are vegan, or who just eat less dairy for environmental reasons, is cows’ methane production — those stinky farts also contain the potent greenhouse gas.

There’s no getting around the product of their poop — organic cows still produce methane — but Jodarski says that the method of managing manure can determine what’s lost to the environment. One Organic Center report says that the best organic farming practices have the capacity to reduce emissions to about half that of bad conventional practices.

In addition to dung, organic farms have an effect on greenhouse gas emissions because they truck in less grain. Jodarski says that the dairy industry as a whole is “moving out of an era with grain prices low,” so the economic and environmental advantages of this aspect of organic milk will become more obvious as gas and grain prices rise.

What’s in a name?

Jodarski says one of the basic talking points of the conventional dairy industry is “milk is milk” — that there’s no nutritional difference between conventional and organic milk. He says such campaigns try to show this by comparing the content between conventional and organic milk’s protein and fat content, which don’t tend to vary a lot, while ignoring data for omega three fatty acids, conjugated linoleic acid and beta carotene. “We’re finding that there’s quite a difference,” he says.

“People say that organic farmers want to go backwards and nothing could be further from the truth,” Jodarski says. He points out that organic farmers embrace good technology, using advances such as solar power on tractors and carefully tracking the health of their fields. “They don’t accept every technology blindly. Chemicals and genetically modified organisms are not acceptable.”

Bansen says that making the jump from conventional to organic brought the science of dairy farming together with what’s best for cows and the planet. “It was an out of balance system. It seemed in balance to me, but I see the difference now,” he says. “We slowed it down to the pace of nature.”