A Stitch in Time

Playin’ it safe with the fight doctor

By Dante Zuñiga-West

You can tell the guy has seen some fierce things, but his low-toned steady voice that sounds like he’s a radio-jockey for some late-night jazz station creates a startling contrast — something like comfort and volition, interlocked. This is good because, chances are, if you encounter him while he is on the job, you’re probably in the midst of a slightly traumatic experience.

Only five people in the state do what he does; 42-year-old Dewayde Perry is not just any medical doctor, he is a fight doctor — a ringside physician.

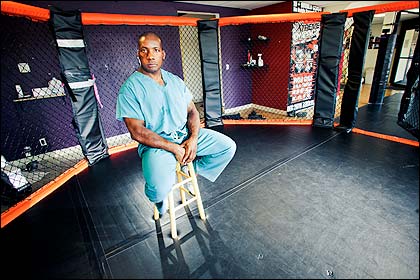

|

| Dewayde Perry at Northwest Training Center. Photo by Trask Bedortha |

Combat sports like boxing, kickboxing, professional wrestling and mixed martial arts (MMA) require sanctioning by the Oregon Athletic Commission, and someone like Perry must be present at every match. Most often he is found working in local and regional MMA competitions. His job is essential to the safety of competitors, who receive pre-fight physical examinations to ensure each is healthy and capable of competing. Perry conducts post-fight examinations as well, to screen for injuries. If sutures are needed, or if a fighter needs to visit a hospital for more care, then that is also Perry’s concern.

“I’ve definitely had to suture up a few guys,” Perry explains. “It’s an easy repair and that’s a minor typical injury. But I have had to send a couple guys to the hospital to get MRIs for bad knockouts or facial fractures.”

While Perry does have a certain say in whether a fight will or will not continue, he is not a cut-man or referee. He isn’t in the fighter’s corner rubbing down swollen eyes, applying Vaseline or wiping up blood — that’s not his gig. Nor is he there to ensure the fighting is conducted in a way that promotes good sportsmanship. That’s someone else’s job.

“The first order for a stoppage is the referee,” Perry specifies, “but for injury-related type of stoppages, that goes to me.”

If a fighter sustains an injury that could put his life at risk or permanently damage his body, like an accidental eye gouge, a huge cut or a serious concussion, the physician will be called into the ring to decide if the competition will be stopped.

Perry has worked amateur shows as well as some of the most high-profile professional MMA competitions in the world. He worked as ringside physician at Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) 102 and the Strikeforce Challengers 8 shows. He was there when Randy Couture fought “Minotauro” Nogueira. He witnessed Eugene fighter Evan Dunham send Marcus Aurelio’s UFC career down the proverbial tubes, firsthand, just after performing a prefight examination on the talented young contender.

Considering his background, Perry is something of an anomaly in his field. A diligent student of the martial arts, Perry spent time in the legendary Chinese province of Henan studying Kung Fu with Shaolin monks. He has competed in Wing Chun point-style tournaments and Jujitsu competitions as well. Currently studying Muay Thai and Brazilian Jujitsu, Perry is a familiar face among some of the most formidable and authentic martial arts gyms in Eugene. He also happens to have been a national award-winning bodybuilder and a master of human anatomy, given his work in general surgery.

“Because I train in combat sports, I feel I’m really able to understand what fighters go through in terms of preparation for their fights and in terms of injuries. And also knowing when to appropriately stop a fight,” he says of his connection to the world of ringside physician work.

Asked about the future of MMA following the UFC franchise’s recent signing of a bright, shiny, seven-year $90-million contract with FOX Sports Net, the doc makes his diagnosis clear: “Fox Sports merging with UFC is a great thing. It will bring martial arts to more people, and hopefully it will help reduce the stigma attached to mixed martial arts by people who really don’t understand the sport.”

He pauses. “Because there is punching and kicking involved,” Perry says, “people think it’s more violent than football or rugby or any other contact sport you see on TV, but it’s not. It’s actually way safer. The same haematomas and lacerations and sprains exist in those other sports too.”

In the world of contact sports, MMA has been labeled barbaric and dangerous — Sen. John McCain once called it “human cockfighting.” But a closer look by the medical community found the sport to be as safe and, in most cases, safer than other combat sports such as boxing and kickboxing. In a 2006 study conducted by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, researchers found that professional MMA competitors suffered the same percentage of injury as professional boxers.

When one compares the safety of MMA to boxing, there is even more to be said. Let’s get real here — what we are talking about is repetitive head trauma and long-term brain damage. This is far less likely to occur in MMA, for two very specific reasons.

First, in MMA, there are myriad ways for a fight to conclude: technical knockout, knockout, submission or decision. This essentially has to do with the inclusion and use of ground fighting such as wrestling and Jujitsu, two combat sports that the Hopkins study found to be significantly less riddled with injuries. A professional MMA competitor can win a match by Jujitsu arm bar just as resolutely as he/she could win by knockout. Arm bars, knee bars, chokes, leg locks — your limb isn’t going to feel good the next morning, but your brain is still intact.

Furthermore, in the MMA community it is considered wise to tap (called “tapping out”) when in the grip of an inescapable submission, so as to secede from the contest but preserve one’s body and career. In boxing, there are only three ways to win: knockout, technical knockout or decision. Your corner can throw in the white towel, but no boxer wants that — it is considered shameful.

Second, in terms of striking: Boxing and kickboxing competitors use 10-ounce gloves; this protects the hand and allows the boxer to deliver a great deal more trauma to the head of his opponent as opposed to just knocking him/her out. Although the notion of a safe knockout may sound oxymoronic, the gloves used by MMA competitors weigh 4 ounces; a well-placed punch from such a glove will simply knock a person out, which is safer than permitting further blunt force trauma to the recipient. “Most amateur MMA fights I’ve seen end by TKO, in general because of the concern for the safety of the participants,” Perry says.

There is also the standing eight-count rule in boxing and kickboxing, which allows a fighter who has been significantly stunned by blows to have eight seconds of recovery time before returning to the fight. MMA has no standing eight count and, as Perry explains, “going back into the fight after already receiving head trauma causes even more opportunity for severe head trauma and brain damage.”

Safe or not, MMA is going big time now, and will be making its way to your standard issue cable TV soon, alongside football, ice hockey and other contact sports, all of which have been criticized as too violent or dangerous.

Similar to those other sports that in this new era will be showcased alongside MMA, the willing participants are as safe as they can be within the context of a contact sport.

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

Table of Contents | News | Views | Blogs | Calendar | Film | Music | Culture | Classifieds | Personals |

|||||||