For all their deceptive genre fluidity, technical finesse and narrative bankability, the Coen brothers remain among our finest filmmakers, capable of straddling that razor’s edge between populist confection and radical seriousness without ever losing their grounding in an artistic integrity that seems, so far, unimpeachable.

Inside every major and minor Coen offering hides an existential wallop that reveals itself slowly, sometimes over the course of years, even decades. Hence, 1998’s The Big Lebowski looks today like a grunt of prophecy on par with Orwell and Hobbes — a bitter pill with a sugar coating of cultish nonchalance that perfectly predicted the nihilism of our present predicament.

Which brings us to the latest Joel and Ethan Coen production, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, recently released on Netflix. Yes, you can see in this choice to forgo the big screen a distinct rejection of the major studios, which are bent more than ever on funding mindless, cynical crap.

As commercialized idiocy and populist pabulum rise to the top of the mainstream, seeking to satisfy the basest mediocrity of mass entertainment, major artists like the Coens are being driven to different realms to fund smaller projects. This is at once depressing, predictable and, should you choose to view it as such — as I do — fortuitous. Some of our best directors are now going to Netflix.

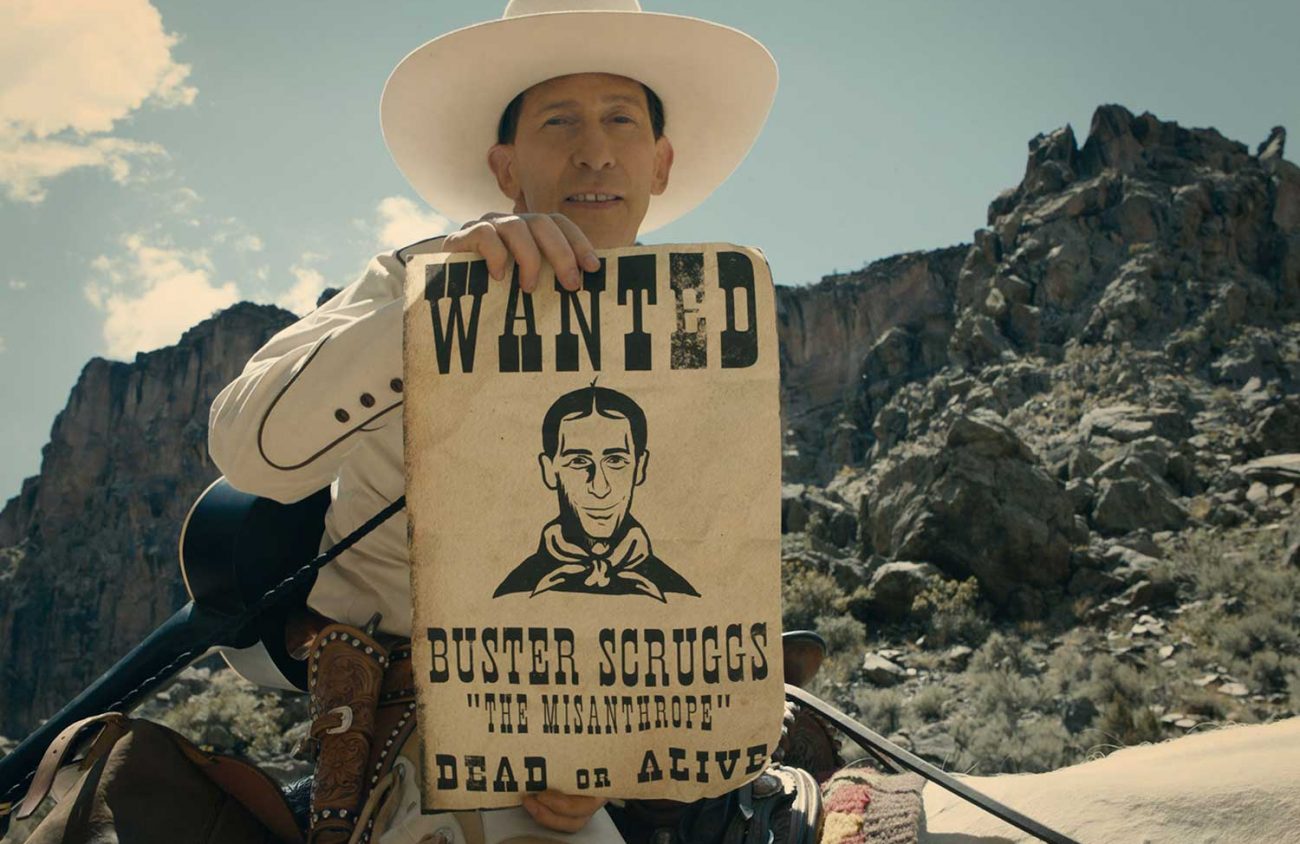

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is quintessential Coens and, at the same time, an oddball entry into their canon. It is an anthology of short films, all based on short stories (written by the Coens over several years) about the American frontier — the kind of dime-store Western adventure stories sometime called “oaters.”

The conceit is distinctly literary, and it plays well in the Coens’ hands. The outward trappings and inward structure of the stories make for straightforward genre potboilers: gunfighters (Tim Blake Nelson), bank robbers and hangings (James Franco), the Gold Rush (Tom Waits), traveling orators and vaudeville (Liam Neeson and Harry Melling), a woman’s trek to new beginnings on the Oregon Trail (Zoe Kazan).

For their first film shot in digital, the Coens lavish the screen with rich, gorgeous details and a palette that is by turns verdant and sepia-tinted. Vast and eye-boggling vistas in one story tighten into a fist of moonlit claustrophobia in the next, creating a dual vision of the West as a place of limitless expanses forever closing in.

Unlike the films of Quentin Tarantino, whose appropriation of genre elements looks increasingly like theft, the Coens explore the Western tradition with a spirit of curiosity and discovery, digging sideways into foundational truths that might just tell us more about ourselves than we’d like to know. In other words, the act of looking at “how the West was won” becomes, for the Coens, a means of understanding how it was lost.

The fatalism and mortality that pervade The Ballad of Buster Scruggs has more in common with the macabre churnings of Edgar Allan Poe and Herman Melville than Louis L’Amour. In each story, idealism — the rigid stuff of dreaming — collides with the utmost limits of human treachery, especially greed, and the results are jarring. The specter of death haunts this movie, sometimes quite literally, and loss is its bittersweet refrain.

One chapter in particular, “Meal Ticket,” provides a strong hint at how we can decipher this strange and hypnotizing anthology. The segment has the compressed punch of a parable. In it, a legless and armless artist who recites great works of the Western canon is driven around the country by an impresario, who collects coins from the grizzled audience, which continues to shrink. To paraphrase a Biblical truth, one cannot serve good and money at the same time. It’s a bridge that cannot be crossed.

The effect of “Meal Ticket” is like watching the lights go out on the Enlightenment itself, and it should be played in every classroom across this accursed nation — a new fable for our fractured age.