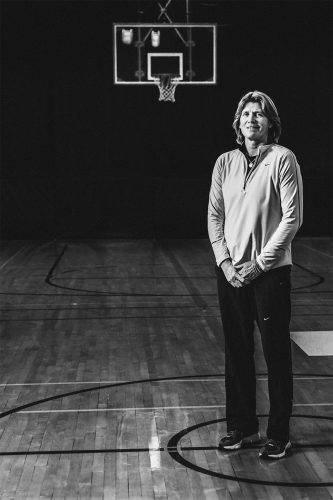

The wall behind Bev Smith’s computer is filled with thank-you notes and team photos of KidSports basketball teams. Smith is still active in coaching, though with a different pool of athletes with different goals: learning to be a good, solid productive person.

Smith has been executive director of KidSports for nine years. Before that, she was a University of Oregon athlete, coach and professional basketball player.

On March 15, Smith was inducted into Pac-12’s Hall of Honor during the conference tournament in Las Vegas. She’s the first woman athlete to be inducted from the University of Oregon.

Smith recalls what it was like playing basketball at the UO just a few years after the passage of Title IX, the federal law ensuring equal opportunity for women in education. Despite the university’s historically unequal investment, she says the UO has become a bit more equitable in recent years, thanks to the growth of interest in women’s sports.

“You don’t get those awards by yourself, particularly when you play a team sport such as basketball,” Smith says about being inducted into the Hall of Honor. “You don’t get to that position without solid family support, so it conjures up a lot of memories and a lot of moments to be grateful for.”

Smith says that, at a moment such as this, she thinks back to every person who pushed her or passed the ball or set up a screen.

“Even your competitors made you better,” she says.

Basketball is still a passion for Smith, though now she incorporates coaching and teaching into that passion. She says she knows firsthand how important great teachers and coaches can be in teaching discipline and positive habits. She wants to pass those values on to the next generation.

“It’s more than the x’s and o’s,” Smith says, adding that it’s not just about the game. “Helping young girls and boys be confident and recognize their confidence is really rewarding.”

Smith started participating in competitive elite basketball at 17. She was able to play basketball and travel the world, she says, and thanks to her coaches, family and teachers, she didn’t go “across the tracks” to pick up bad behaviors.

Instead, Smith came to UO to play basketball when women’s sports weren’t as well supported as the team is today.

She recalls disparate investment from the UO in women’s sports. The men’s team would fly by plane, but the women had to take a van or rent a car to compete at other schools. Rather than wearing top-of-the-line Nike apparel like the two teams do today, she says the women’s team had to wear generic athletic clothing. They were lucky to receive just a pair of shoes.

“We noticed the difference with the men, but it didn’t prevent us from pursuing our passion,” she says. “We were going to be out there whether we got any shoes, because we loved playing the game.”

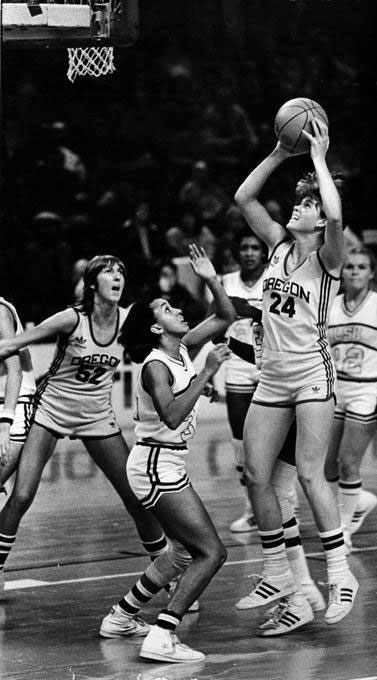

When Smith was a freshman, she says, it was the first year that the team was able to play at McArthur Court on its own and not as a warm up act for the men’s team. That’s because fans were saying they didn’t want to buy a ticket for the men’s game and wanted to support the women’s team.

Women’s games were attended by a sprinkling of fans, Smith says, but when the South Korean national team toured the U.S. and showed up to play the UO in spring 1979, the audience packed the bleachers. Five thousand people were in attendance for that game, and it was the first time Smith says she played in front of that many people.

The large draw, she says, didn’t affect the team’s performance.

Enlarge

Photo by Brent Wojahn

“Five thousand people in that lower bowl in a wooden facility, I’m sure the South Koreans were shocked at how loud it could get in there and how much support you could feel,” she says. “We were the gladiators out there.”

UO went on to win the game by one point.

A victory in that game helped establish a buzz about the team, inspiring people to follow the women’s team, Smith says.

Women’s sports has grown over the past 30 years since Title IX’s implementation, in large part due to the work the athletes have done on the court, in the classroom and the community, Smith says. This has helped establish a generation of women athletes to which today’s athletes can be compared.

“Years ago when I played, people would say, ‘Oh, you’re the Larry Bird of women’s basketball,’ and my mom was always like, ‘Well, that’s a compliment to him, not you,’” she says.

“Now, though,” Smith continues, “Sabrina [Ionescu] can be compared to myself, Denise Curry or Cheryl Miller. There’s context now that makes it our game.”