The story of Dick Fosbury just might be as important to this state as the legend of the Oregon Trail. Longtime Register-Guard columnist and local author Bob Welch says he was surprised, when he approached Fosbury about the idea writing a book 50 years after the “Fosbury Flop,” that there wasn’t a long line of writers waiting to tell the story.

Telling Fosbury’s underdog story earned Welch the 2018 Book of the Year award from Track and Field’s Writers of America. That’s because there’s more to Fosbury’s story than just approaching the high jump differently.

Co-written by Welch and Fosbury, The Wizard of Foz: Dick Fosbury’s One-Man High-Jump Revolution tells an underdog tale of a man desperate to succeed in the high jump and then experiencing a political wake up.

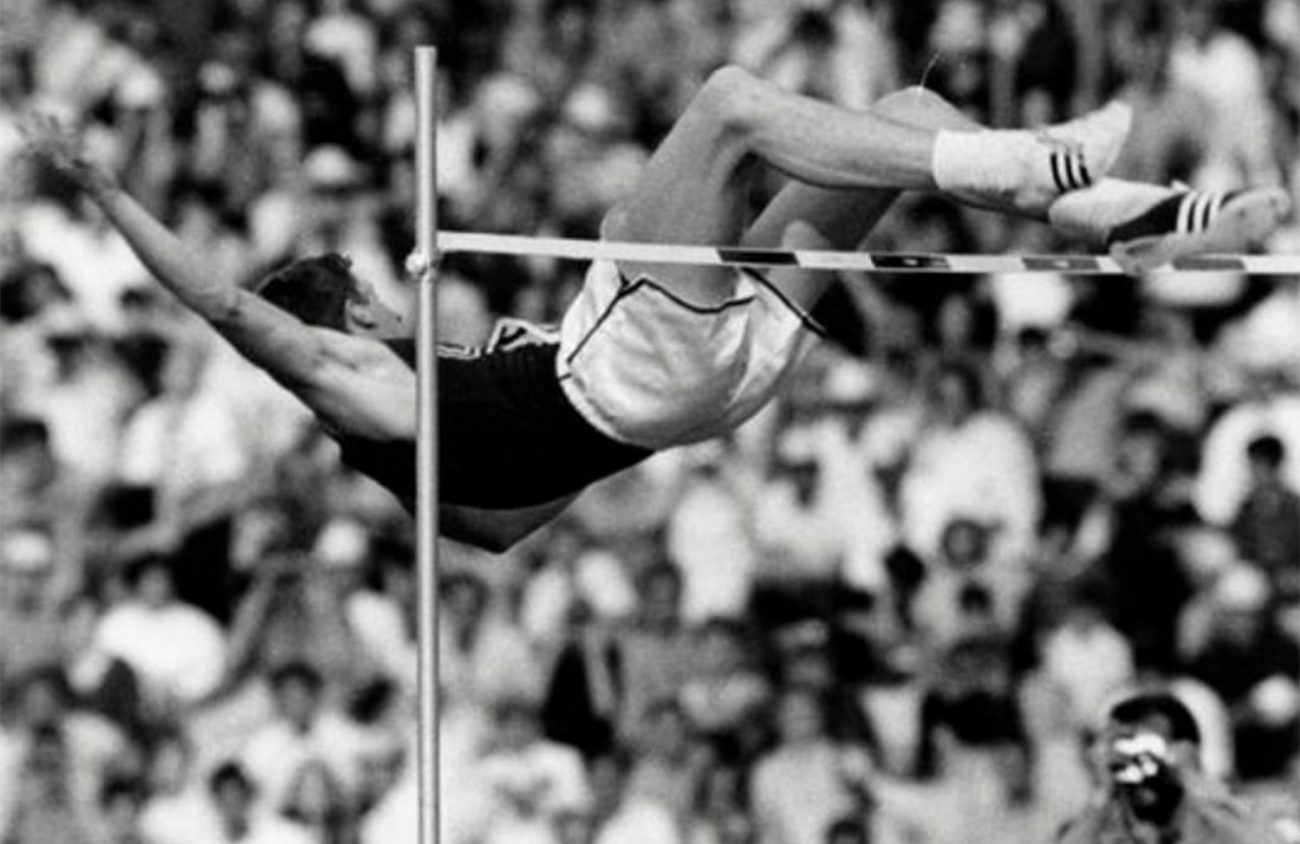

Fosbury never could master the traditional “straddle,” writes Welch in his book. Instead, he approached the high jump backwards and landed on his lower neck and shoulders. This resulted in the introduction of padded landing mats to replace a sand pit.

Fosbury won the gold at the 1968 Olympics. He was the 1968 and 1969 NCAA champion. His accomplishment in track and field is still relevant to collegiate athletics; he was inducted in the Pac-12 Conference Hall of Honor in March of this year.

These accomplishments didn’t come easy. Fosbury revolutionized the high jump, but he wasn’t a natural high jumper. He was the worst jumper on the Medford High School team, Welch says.

Deep within Fosbury, according to Welch, was the “power of desperation.”

Fosbury had lost his brother when the two were riding bicycles together. A year later, his parents divorced. So he was sort of orphaned by the time he was 14, Welch says.

“Track is really his only hope, and he’s really bad,” the writer adds in an interview with Eugene Weekly. “Sometimes desperation leads to the most imaginative solutions. For him, it changed his life, and it did change the world.”

To change the world, Fosbury had to fight social norms. Welch says one of the morals of Fosbury’s story is the importance of persevering.

“Coaches said it was illegal. Doctors said he was going to break his neck. There were a million reasons why Fosbury should’ve just said, ‘Oh, forget it,’” he says. “Of course, he got the last laugh.”

To contextualize the resistance Fosbury encountered, Welch says that it would be like if a quarterback suddenly decided to throw the ball backwards. The 1960s, of course, were all about the young generation butting heads with the older generation. When Fosbury won the gold in Mexico City, coaches listened.

“Winning a gold medal is like going to the moon,” Welch says.

Of course, none of Fosbury’s accomplishments — or anyone’s — happen in a vacuum. Current events shape our everyday life. Welch says the book became more of a history book, not just a story about a revolutionary way of high jumping. In fact, Welch’s own mom thought it was more of a history book.

The Wizard of Foz starts with JFK’s pledge to land a man on the moon and, as Fosbury’s story is told, it includes the struggle for civil rights, anti-Vietnam protests and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Welch remembers his bedroom wallpapered with Sports Illustrated photos when he was growing up in the 1960s. Among them were photos of the Echo Summit, the 1968 training site for the U.S. Olympic Trials and Training Camp.

Fosbury, along with Welch, revisited Echo Summit during the process of writing the book. The apex of Fosbury’s career was the 1968 Olympics, Welch says, but what he experienced at Echo Summit was “an amazing feat.”

That’s because Fosbury had to endure another challenge. When he arrived at Echo Summit, a mountain pass over the Sierra Nevada at an elevation of 7,382 feet, Fosbury thought he had a spot on the team but was met with a note on the door. The U.S. Olympic Committee was changing how it would select squad members. He had one week to prepare.

“There was a lot of pressure on him,” Welch says. “There were a couple of guys, no names, who were jumping extremely well, and he was in fourth place. Only three made the team, and he was the underdog throughout the entire competition.”

In his book, Welch recalls the tension as four high jumpers vied for the spot on the U.S. Olympic team to go to Mexico City. Fosbury failed twice to clear 7-feet 2-inches. If he failed one more time, he’d be watching the 1968 Olympics at home.

Instead, he cleared the bar by two inches. When the bar was raised another inch, Fosbury cleared it. The next high jumper nearly cleared the bar but nudged it with a trailing leg.

Fosbury was going to the Olympics.

“To me, that was the essence of Dick Fosbury,” Welch says.

After the 1968 Olympics, Welch says Fosbury had a political awakening. It was the same Olympics at which Tommie Smith and John Carlos delivered a Black Power salute during the medal ceremony.

When Fosbury went home to Medford, he was asked how he felt about the salute. Residents thought he’d issue a condemnation. Instead, he supported the athletes.

Fosbury got in trouble at Oregon State University when he supported Fred Milton, a black OSU football player who was dismissed from the football team for having a thin mustache and goatee during the offseason. Milton said it was a violation of his human rights. The Black Student Union (BSU) said it was a symptom of structural racism on campus.

The incident led to dueling rallies. Fosbury supported BSU, and that political stance was a turning point for Fosbury, Welch says in the book. After standing up for Milton, he was either loved or hated by the OSU community.

Fosbury gave up on track and field after winning the gold in 1968 and reinventing the high jump. Welch says the high-jumper’s rise was meteoric.

In 2018, he jumped into the world of politics.

Now living in Idaho, he challenged a longtime Democratic county commissioner in the 2018 Primary Election. In November 2018, he was elected to Blaine County Commission.

Fifty years after the 1968 Olympics, Fosbury is still shaking things up.

Help keep truly independent

local news alive!

As the year wraps up, we’re reminded — again — that independent local news doesn’t just magically appear. It exists because this community insists on having a watchdog, a megaphone and occasionally a thorn in someone’s side.

Over the past two years, you helped us regroup and get back to doing what we do best: reporting with heart, backbone, and zero corporate nonsense.

If you want to keep Eugene Weekly free and fearless… this is the moment.