Even before an oil train derailed and spilled its contents in the Columbia Gorge in 2016, the black tankers and their dangers were an ongoing concern in Oregon. House Bill 2209, which recently passed by a 56-3 vote in the Oregon House of Representatives, hopes to address that concern by requiring railroads carrying crude oil to come up with contingency plans of their own.

Legislators such as state Rep. Marty Wilde, who was part of the House Interim Committee on Veterans and Emergency Preparedness that came up with the bill, say they hope HB 2209 will make emergency response to spills quicker and more effective.

The contingency plans must have the Department of Environmental Quality’s (DEQ) approval as the primary state agency. Railroads must also provide a copy to the state Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Department of Land Conservation and Development and the Office of the State Fire Marshal (OSFM) for review.

What is different with HB 2209 is that instead of having only state agencies working in emergency preparedness, railroads will have a bigger role in keeping Oregon safe from an environmental disaster.

Annalisa Bhatia, DEQ’s senior legislative advisor, says that railroads would have to include in the contingency plans “where they’re operating, who’s in first in terms of their personnel in a given area, what equipment they have in a given area.”

The worst-case scenario when it comes to an oil train derailment is Canada’s Lac-Mégantic. In 2013, a 74-car train carrying approximately 2 million gallons of Bakken crude oil at 65 mph derailed, and 75 percent of the oil spilled and exploded in the city of Lac-Mégantic, killing 47 people. Half the downtown area was destroyed.

HB 2209 sets a worst-case scenario spill of 15 percent of a train’s load — 60 percent less than the Lac-Mégantic disaster.

Three years later, a Union Pacific train carrying nearly 3 million gallons of Bakken crude oil derailed and spilled 42,000 gallons in the Columbia River Gorge near Mosier. The incident led to a fire, which was put out with no injuries. No substantial amount of oil spilled into the Columbia River.

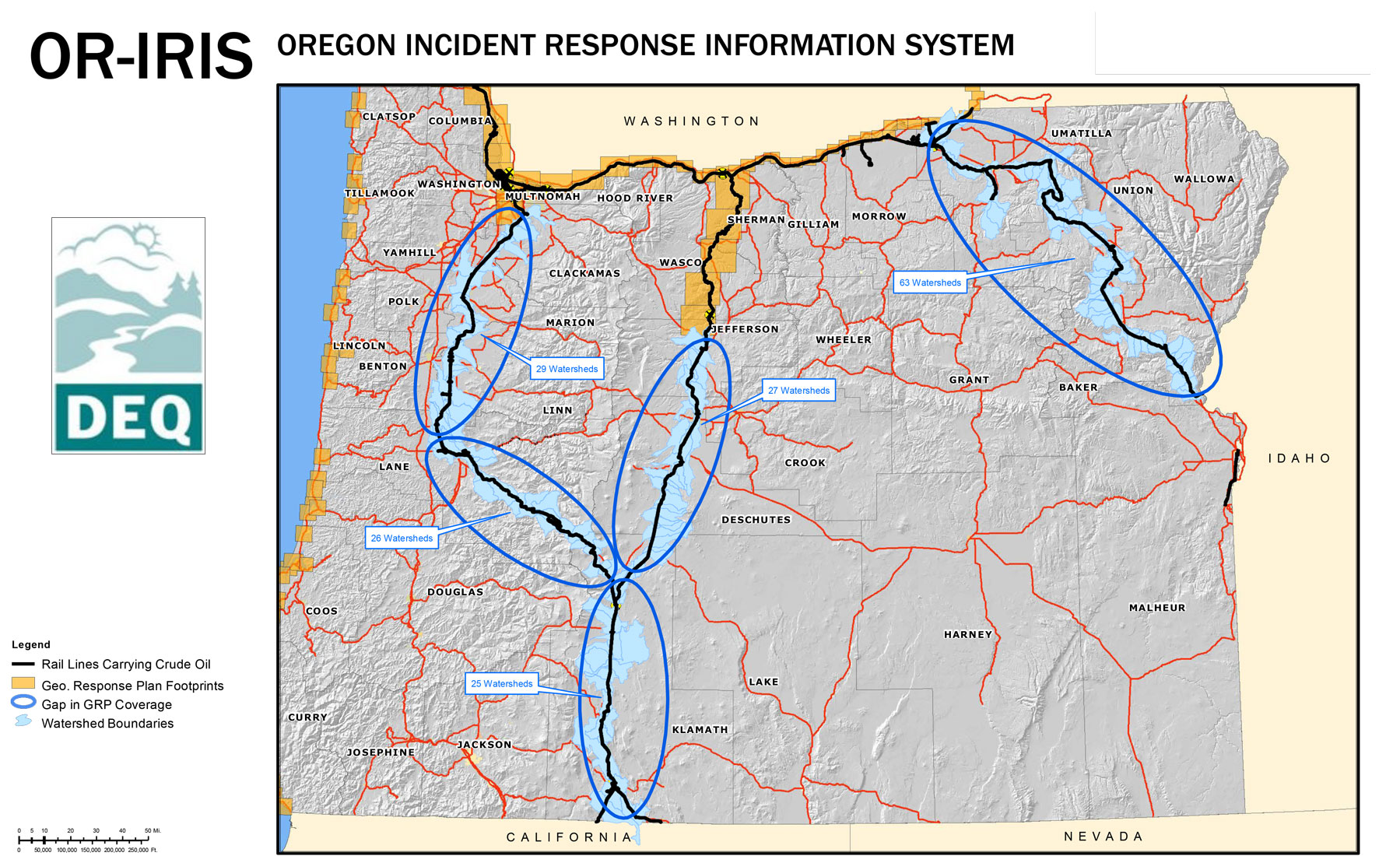

The Columbia River is one of three regions where the DEQ has geographical response plans (GRP) in place. The Oregon coast and part of the Willamette River are other regions. But according to a DEQ map, many areas of Oregon, including Eugene, have oil train rail lines but no GRP.

With HB 2209 in place, railroads have to come up with their own contingency plans approved by the DEQ. With the information provided by the railroads, DEQ would be able to come up with better GRPs, Bhatia says.

“That information to the department works in these larger geographic response plans, so that feeds into the information that we already have from local governments too,” she says. “So we can put together a cohesive plan for this given area.”

The priority for DEQ in creating the GRPs throughout Oregon are natural resources and places with economic and cultural value, says Scott Smith, DEQ’s emergency response planner. That includes rivers and fish beds, for example.

The area that includes Eugene in DEQ’s map has 26 watersheds but no GRP.

Once the DEQ evaluates the resources such as water supplies adjacent to the rail lines, the next step is sending equipment and developing strategies that would not exist if not for contingency plans, says Mike Zollitsch, DEQ’s emergency response manager.

Although HB 2209 can lead to a more effective way to respond to an oil train spill, Michael Heffner, assistant chief deputy with the OSFM, says it will not influence the HazMat (short for “hazardous materials,” such as Bakken crude oil) by Rail Transportation coordination plan set in place.

“For the last four years the Office of the State Fire Marshal has delivered thousands of hours of training, we’ve coordinated with eight counties to implement a county-wide HazMat By Rail,” Heffner says. “Then we have distributed equipment, including eight fire fighting trailers around the state.”

According to the HazMat by Rail plan, the OSFM has three stages of emergency procedures: emergency response, consequence management and environmental restoration. The OSFM also works with the DEQ to assess the responsible parties in the spill.

Having the railroads’ contingency plan will not affect this procedure, Heffner says, but HB 2209 does provide for more funding and training.

With the funding, the OSFM would apply a three-year plan that includes table talks, and functional and full-scale exercises of train derailments, Heffner says.

Besides the requirement for contingency plans, railroads will also have to pay a $20 fee for every car containing Bakken crude oil. With this, it is expected that DEQ and the Fire Marshal will have a fund of $1 million every two years to be used for training until it is canceled in 2027.

“The best part of this is that it won’t come out of the taxpayer’s pocket,” says Lisa Arkin, executive director of the environmental nonprofit group Beyond Toxics. But she also says that HB 2209 will hardly dis-incentivize railroads from transporting Bakken crude oil through Oregon.

The oil comes from North Dakota and Alberta, Canada, says DEQ’s Smith, and started going through Oregon in 2012 when oil production started booming.

The solution to the risk that oil trains bring to Oregon, Arkin says, is stopping the use of fossil fuels altogether. She cited HB 2020 as the example of a bill that can curb the use of fossil fuels through carbon emission caps.

But for Rep. Wilde, HB 2209 is a step in the right direction. “It took a while, but we finally got there,” he says.