Time is running out for management from Oregon’s seven universities and classified staff to agree on a contract before labor can vote on a strike.

The universities’ management says there’s not enough money for staff to get what they’re asking for. The union says management’s offer doesn’t meet living costs and that universities prioritize the wrong expenditures, as a result suffering from administrative bloat. And, at a time when organized labor has more public support than ever, some workers are tired of these priorities.

Among other demands, Service Employees International Union Local 503 (SEIU) wants a cost of living adjustment (COLA) of 7.25 percent over two years. But the universities propose 2.5 percent COLA and wage step increases. The universities’ proposal cites the salary step program as a wage increase, but employees who have already maxed out on step increases would only receive the COLA.

SEIU 503 represents classified staff at the seven universities who work in office, food service, custodial and other positions.

“The offer management has given us doesn’t meet living costs,” says Johnny Earl, an SEIU chief bargaining delegate for the University of Oregon. “The value of our dollar is diminished. Our buying power is decreasing.”

He adds that it’s not just about the money — it’s about respecting the workers who are often the last to get wage increases.

If universities received more money from the Legislature this year, the state would increase its offer to classified workers, says Di Saunders, a spokesperson for the seven universities during the bargaining process.

The universities offered SEIU less money before the Legislature released its biennial funding to higher education, but increased the offer after receiving an extra $100 million from the state.

If the universities accepted SEIU’s proposals, the increase in classified costs would take up to $55 million out of that money, Saunders says, and could push up tuition.

She says that would be unfair to those students and their family who are already struggling to pay tuition.

SEIU collaborated with consultant Daniel Morris to examine the state’s seven universities’ budgets, which suggests universities are prioritizing “administrative bloat, athletics and capital projects over good jobs and affordable in-state tuition.”

According to the UO’s Office of Institutional Research, the UO has 1,603 classified staff employees and 1,493 officers of administration. UO interim spokesperson Kay Jarvis says not all officers of administration supervise classified staff, but some do.

Morris’ report says the average worker-to-supervisor ratio of all universities is 5.43-1 — the UO is 5.59-1. The average of all other state agencies is 10.29 to one.

The report also looks at some employees who earn the largest sums of any public worker in the state. The top salary-earner is UO President Michael Schill, who receives an annual salary of $734,400 — or $32,276 a week.

The report found that the average state’s university full-time classified worker earns $45,367 a year and the average part-time worker earns $16,869.

When asked about universities paying high salaries for administrative personnel, Saunders says comparing the salary of an employee who is “managing a donor relationship or portfolio” to that of a food services worker is inappropriate.

She adds that universities try to pay market rate, whether the employee is in administration or food service.

“Can we match that 100 percent? No, we can’t, because in Oregon we have less funding than other states,” she says.

One of the proposals pushed by the UO was to eliminate a meal discount for dining services employees. Currently, the UO’s dining services employees pay $1 for meals, but the UO wants those employees to pay $3 like every other employee on campus. One-dollar meals don’t cover raw food costs, according to the UO.

Saunders says she’s surprised that the SEIU has taken a strong stance on that proposal since it impacts a small pool of employees.

Food service employees have some of the lowest salaries at the UO, SEIU’s Earl says. Those employees used to receive free meals, but then management added a $1 charge. Now, UO management wants those employees to pay $3 for a meal, as student workers already do.

“We can’t pay them more, and now we want them to pay more for food,” he adds.

SEIU bargaining representatives and universities have three more bargaining sessions to work out a contract both parties can agree on, until the union’s members can vote on a strike. The earliest the union could strike is Sept. 23.

The last time universities’ SEIU-represented staff went on strike was in 1995.

If a strike does occur, the UO says it is taking steps to identify ways to fill vacancies, which include limiting or stopping non-essential functions, shifting duties and covering vacancies through temporary staffing agencies, Jarvis says in a statement.

Earl says he hopes the bargaining works out, but the union is willing to take that next step.

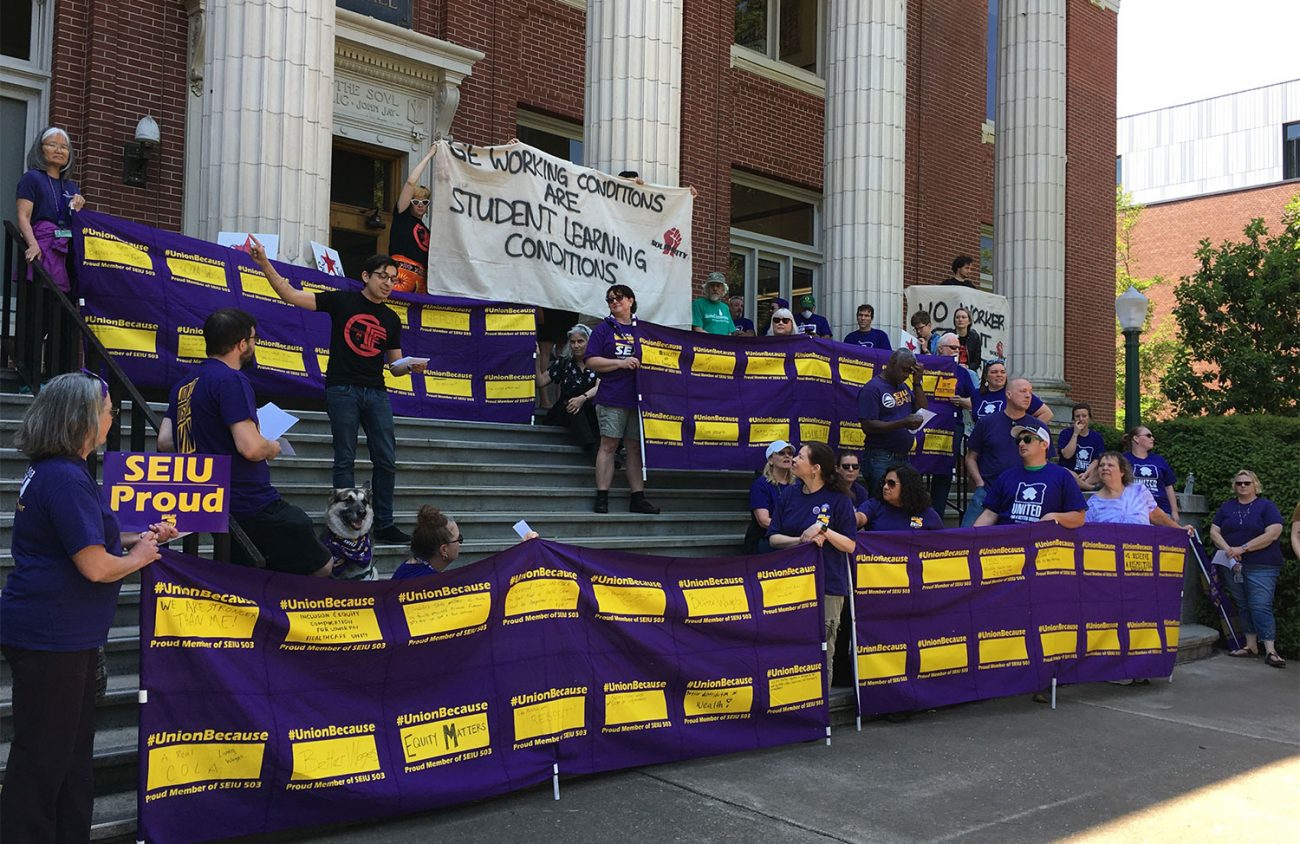

When SEIU held a rally in June about negotiations, union representatives, such as Executive Director Melissa Unger, said they weren’t afraid to flex their muscle and go to a strike.

Support for unions has grown recently. A Gallup poll released Aug. 28 suggests 64 percent of Americans support organized labor — a 50-year high, according to the polling group.

In addition to a shift in public thinking and years of furloughs and pay freezes, it’s the “perfect storm,” Earl says.

“We have more momentum now than we ever have because people are sick of taking it,” he says.

This story will be updated at EugeneWeekly.com if developments occur during the Sept. 11-13 bargaining sessions.