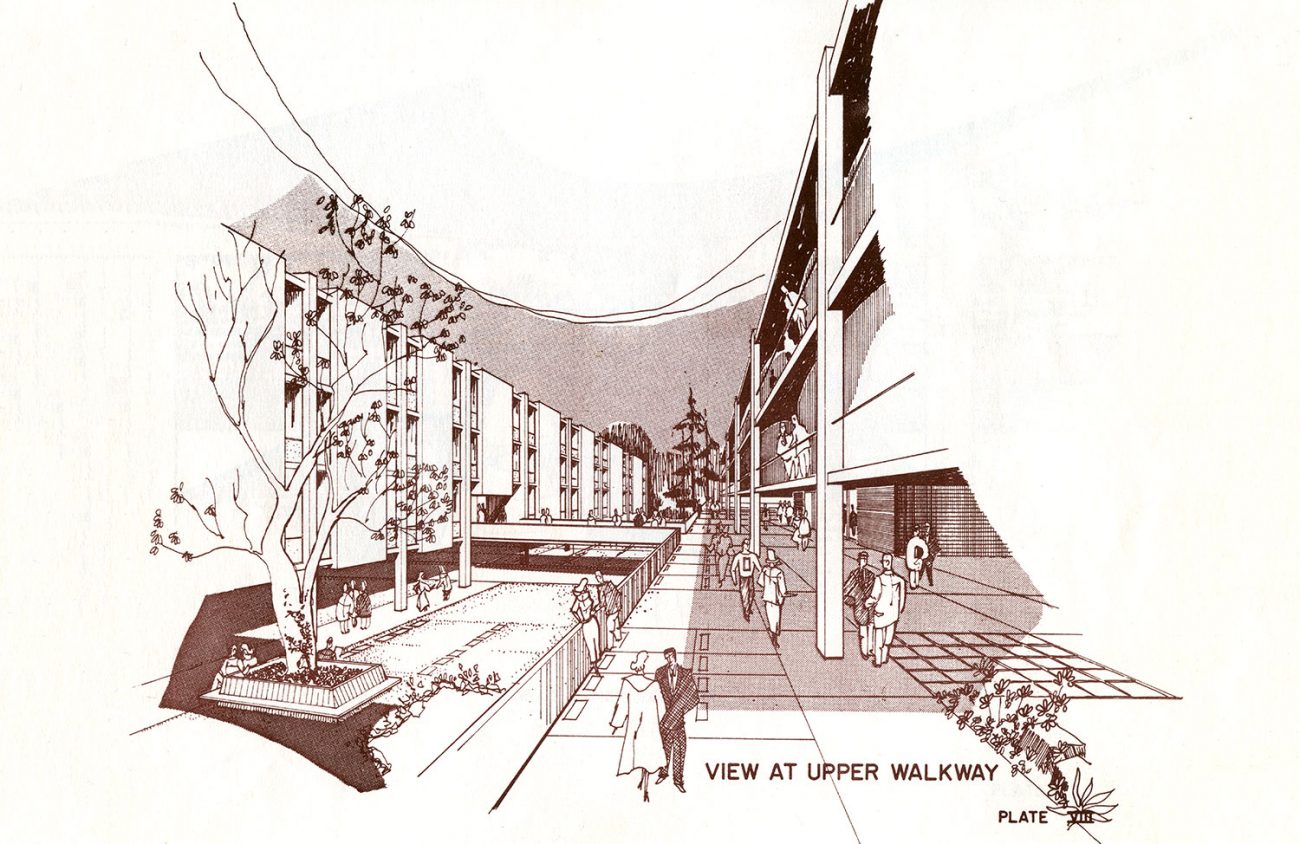

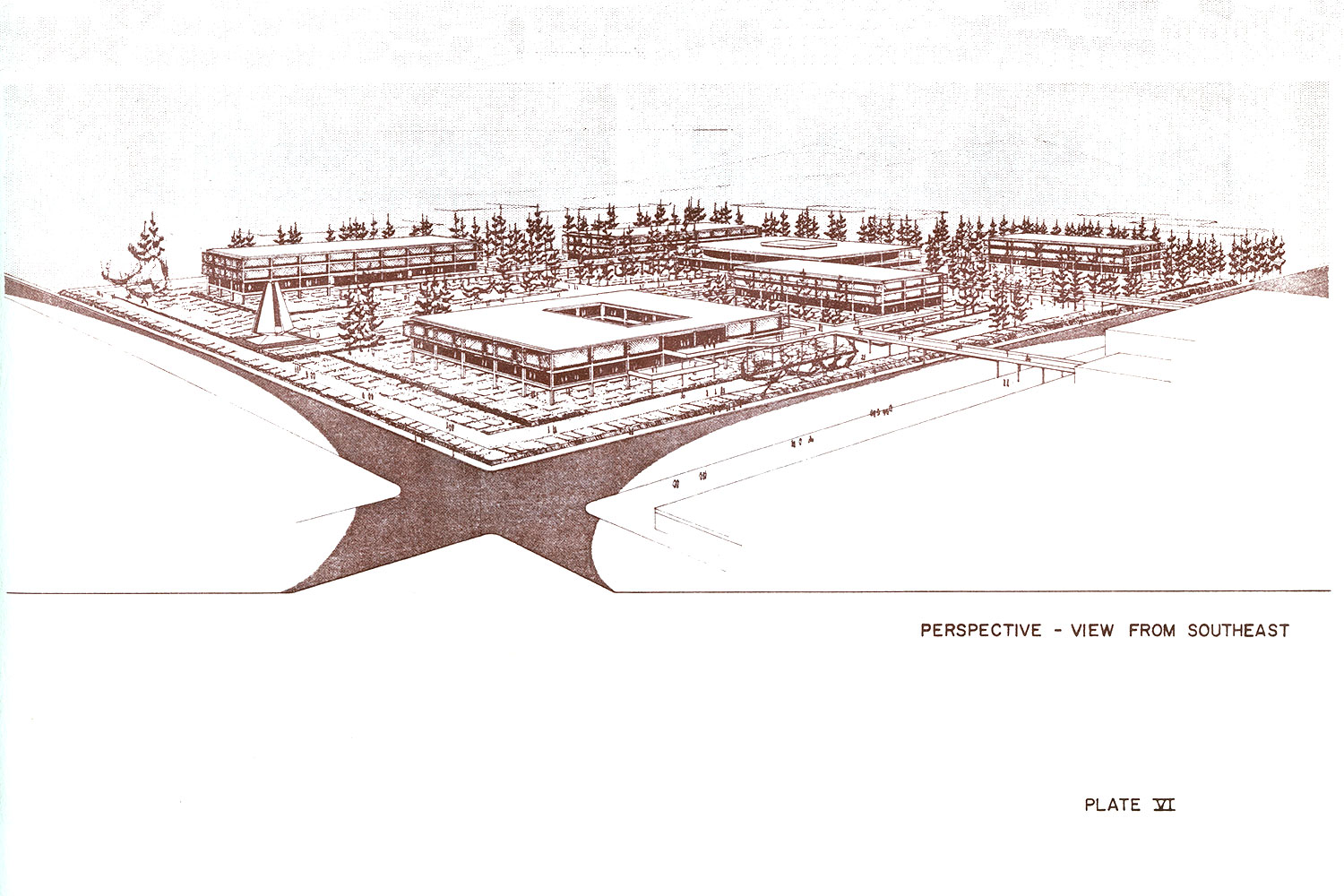

Students happily mill past cemetery markers, while buildings rise high above the graves. This surreal scene appears in drawings from 1963 showing a proposed addition to the University of Oregon campus: structures sitting on pilings over the Pioneer Cemetery.

The idyllic sketches make the cemetery on the south edge of campus look almost parklike beneath the edifices, with the long-buried dead a minor afterthought to the aspirations of higher education.

It’s sketches like these, as reported in the Daily Emerald back in the 1960s as well as a couple of student theses on the topic, that allowed Eugene Weekly to piece together the University of Oregon’s buried history with the Pioneer Cemetery — a moment when the UO decided it was a good idea to erect buildings over the dead.

Roxi Thoren, associate professor and department head of Landscape Architecture at the UO, sheds light on the architectural thinking. She says, cemetery aside, the idea of an elevated building was “standard architecture of the time.”

She says the idea comes from French architect and modern architecture pioneer Le Corbusier’s idea of a tower in the park. It’s “supposed to be a continuous horizontal green plane, and the city will be this expansive garden,” she says.

She calls the thinking of the time progressive and technocratic. “It’s about technology freeing us from the vicissitudes of nature,” Thoren says.

But looking back, the plans look strangely out of touch.

Although a bit weird, the university’s aspirations probably don’t shock anyone familiar with the “University of Nike.” Even before being flooded with Phil Knight’s money, the UO was ambitious. The university in 1963 was doing exactly what it’s doing now: casting its gaze on nearby land, seeking to acquire real estate and build not only new academic buildings, but its reputation as well.

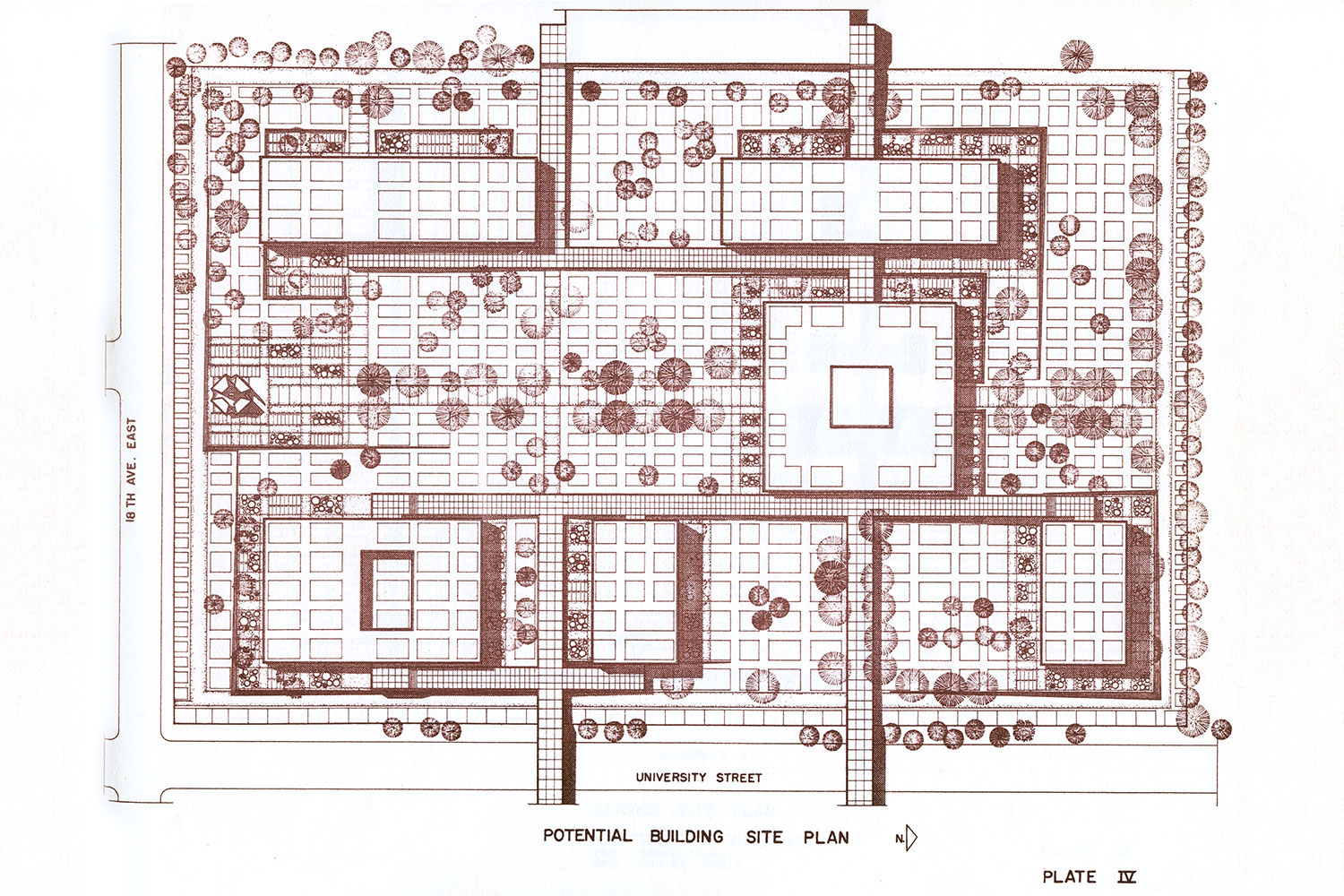

In 1963, the architecture firm Lutes and Amundson created five plans for the UO to expand onto the land occupied by the Pioneer Cemetery. The most ambitious — and most unbelievable — was an idea to construct buildings over existing graves, presumably without disturbing them.

Thoren says the tower-in-a-park idea is a nice one, but she calls some of the unbuilt design examples, such as the plan for the cemetery, a bit extreme. “A tower in a park is one thing,” she says. “A tower in a cemetery is another.”

She adds that architects of the period often did not think about the world as it existed around them. They saw their desire to build as something paramount to the needs and limitations of the space it would inhabit.

The non-engagement with pre-existing conditions seems to have been at play with Lutes and Amundson and the UO. The plan depicts a landscaped graveyard with footpaths for students to walk on. Above them are buildings vaulted and supported by beams. Skybridges direct students from other areas of campus to their over-the-cemetery classrooms.

Basically, the UO wanted so badly to expand that it was willing to put buildings on stilts over a graveyard.

“That is shocking,” says Ocean Howell, associate professor of architectural history at the University of Oregon Clark Honors College, looking at the architectural drawings. He’s shocked not only by the premise of the plans themselves, but also by the fact that they were seriously considered in 1963.

Whose Cemetery?

Long before plans were made for grand buildings and skybridges above the cemetery, quieter plans arose to challenge the governing body of the Pioneer Cemetery. A fracture within the Odd Fellows Cemetery Association led to more than a decade of disputes over the land, many of them involving the university. The Odd Fellows Lodge owned the cemetery at the time.

The association split into two groups: the Odd Fellows Cemetery Association and the Pioneer Memorial Park Association. The Odd Fellows believed the new Pioneer Association wanted to hand over rights to the university.

Down the line the Odd Fellows changed the name of their association to the Eugene Pioneer Cemetery Association in hopes of disassociating with the Lodge and getting the rights to the property back.

The two groups went to court and, at one point, the Eugene Pioneer Cemetery Association argued that the Pioneer Memorial Park Association had allowed the cemetery to become so overgrown that it “constituted a fire hazard besides having an unsightly appearance.”

The five plans created by Lutes and Amundson called for the university to convert the cemetery into usable academic space. The strangest of them was the Le Corbusier-esque tower-in-the-cemetery idea.

This idea was backed by state Rep. Ed Elder and was known as Elder’s Compromise.

The plan included utility tunnels and vehicular circulation that “could be located within 30 feet of roadways where excavation without disturbing graves would be possible.” The plans also say “some ground floor service areas and stairways could be located in vacant grave areas.”

Howell told EW that it would, in fact, not be possible to construct to this scale above a cemetery without disturbing graves.

Much of the record over the debate comes from the Daily Emerald’s assiduous reporting on the university’s interest in the cemetery for several months.

In 1969, a bill was introduced in the Legislature that would allow for the cemetery to be condemned, then absorbed into the university and built over. It was not the first bill of its kind and, like the others, the bill did not pass.

The other plans for the cemetery that Lutes and Amundson offered seem to have gotten lost in the buzz of Elder’s Compromise.

One alternative to building over the cemetery was a plan for a “relocation in kind” which involved creating a duplicate of the existing cemetery somewhere else in Eugene, and moving the bodies to the duplicate cemetery. This would have freed up land for any building project the UO might’ve had.

Lutes and Amundson also suggested a relocation of the graves with a more consolidated design and relocation to a perpetual care cemetery where a fund is used for general maintenance and repair of cemetery grounds or, finally, a compression of the cemetery on the existing land.

The buzz over developing the cemetery finally died down for good when the university expanded elsewhere and the cemetery was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Then and Now

These days, the UO is no longer trying to expand on or above the Pioneer Cemetery, but it is expanding nonetheless.

In December 2018, the university released its 10-year capital plan detailing how, over the course of the next decade, the university plans to renovate existing buildings and build new ones.

When asked about the plan for buildings on stilts above the cemetery, Michael Harwood, associate vice president and university architect at the UO, says, “I never realized we had this bad idea.”

As far as current involvement with the cemetery goes, Harwood says one of the university’s staff members sits on its board, but that’s the extent of it.

The 10-year capital plan is “our attempt to lay out for the future our capital needs,” he says. He calls the plan the “third link in a chain” that starts with an academic plan, followed by a space plan that assesses what spaces on campus are going to grow.

Harwood says there aren’t many new buildings in the plan “because we think that the space we have will accommodate our growth at the moment.”

Existing buildings will be renovated to be more accessible to alter-abled students, faculty and staff. Plumbing, mechanical and electrical systems will be replaced to “reduce the energy and maintenance costs,” according to the plan.

Some new buildings that were in the plan, such as Tykeson Hall and the Lyllye Reynolds-Parker Black Cultural Center, are finished and in use in the 2019-2020 school year.

Perhaps the biggest change to the UO is the creation of the Phil and Penny Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact, which has already displaced several businesses on Franklin Boulevard.

The Knight Campus is not to be confused with the Knight Library, the William K. Knight Law Center or the Matthew Knight Arena, which are existing buildings for which the Knight family has made financial contributions to fund construction or renovation over the years.

The 160,000-square-foot first phase of Knight Campus is projected to be completed by 2020, according to the University of Oregon 10 year capital plan. Around the O says the Knight Campus is a “$1 billion initiative aimed at integrating research, training and entrepreneurship into a single, nimble, interdisciplinary enterprise.”

Historic Hayward Field was under construction the entirety of the 2018-2019 school year and is being pushed through for spring 2020, including late night work. It’s a prime example of history that did, in fact, get destroyed at the hands of the university when Phil Knight waved a good chunk of change in front of them and other donors followed suit.

The historic East Grandstand, where fans once watched Steve Prefontaine run by, was demolished, despite public outcry, protests by local activists and a call to preserve the structure.

According to the university’s online information, once renovations are completed, Hayward Field will include a new nine-lane track, spacious seats and a tower in the northeast corner that will feature “interpretive exhibits” and an observation deck.

The UO declined to discuss the Hayward tower with EW, referring reporters to the website, so Eugene will have to wait until track season to find out what exactly these “interpretive exhibits” are.

Hayward Field will also house classrooms and labs for the department of human physiology.

The Future of the University

Landscape architecture professor Thoren says that, for the time, ideas like the one for the cemetery were progressive and idealistic, but when we look back with hindsight they look a bit silly.

Time will tell if the same can be said for the university’s new and future developments.

In her work, Thoren is interested in “the role that place and landscape have in reinforcing cultural identity and also helping to create cultural identity.”

“One of the things that I love about this campus is the role that the landscape plays in structuring. It has a figure, and buildings fit into that figure,” she says. “But the landscape rooms are themselves important.”

Thoren adds, “If we begin to lose the landscape, we begin to lose part of what makes us the University of Oregon.”

Exhuming the Cemetery Dispute

Founded 1872 by Spencer Butte Lodge No. 9 of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, Pioneer Cemetery was formally platted in 1892. Years later, a dispute arose over just who was the governing body of the Pioneer Cemetery.

According to The Eugene Pioneer Cemetery: A Historical Overview by Elizabeth Oster, a man by the name of Ben Dorris called a meeting in 1954 of the Odd Fellows Cemetery Association.

The Odd Fellows Lodge had owned the cemetery for many years but had failed to live up to the standard of maintenance that new cemetery laws required. The meeting appointed a new board of trustees in hopes of better maintenance.

The new board staged a takeover and executed articles of incorporation under the name Pioneer Memorial Park Association.

The stated purpose of this new organization was “to acquire the interests in the cemetery property held by the Lodge and the Odd Fellows Cemetery Association and to operate and maintain it on a businesslike basis.”

Others believed that the association’s true objective was to secure the title of the property so the cemetery could be destroyed and the land could be sold to the University of Oregon. They believed the new board was setting the stage for a business deal with its next-door neighbors.

In her 2012 thesis on the history of the Pioneer Cemetery, Elisabeth Kramer writes, “The relationship between the UO and the cemetery is like any association between longtime neighbors.”

To make things even more complicated, two years after the coup, in 1956, the Odd Fellows Cemetery Association changed its name to the Eugene Pioneer Cemetery Association in hopes of disassociating itself from the Lodge and once again acquiring the rights to the cemetery from the Pioneer Memorial Park Association.

Almost a decade passed and in January 1963 the UO wanted to expand but found itself bumping up against the nearby cemetery. Local architecture firm Lutes and Amundson created plans for the UO’s potential expansion.

In the midst of all this arose “Elder’s Compromise,” named after Oregon state Rep. Ed Elder, which proposed the plan, detailed by Lutes and Amundson, of constructing buildings above the cemetery, allowing for both expansion and preservation, on some level, of the historic cemetery.

A Daily Emerald article from Feb. 14, 1963, “Bridge It or Build On It, But By All Means Buy It,” urged the university to purchase the land and decide what to do with it, and supported Elder’s Compromise.

Another article quotes Harold Edmunds, chairman of the cemetery association, as saying the association “will give consideration to anything the university thinks practical…”

In September, the Eugene Pioneer Cemetery Association, the group that wanted to preserve the property, and the Pioneer Memorial Park Association, which owned and was responsible for maintaining the property, went to court. The Eugene Pioneer Cemetery Association charged that the Pioneer Memorial Park Association allowed the cemetery to become overgrown and unsightly.

Meanwhile, the Daily Emerald published yet another article about the cemetery controversy in October, saying, “The petitions filed last month alleged that it is not the intention of the present association directors to maintain the cemetery but to make available to the state board of higher education portions for the university campus.”

This reflects the suspicions of those who believed the Memorial Park group had all along intended to sell the land.

The case litigated until August 1964, when the Pioneer Memorial Park Association was dismissed from court because it proved to a judge that it “did not have the funds to maintain the property and no means of acquiring any.”

The Pioneer Memorial Park Association was freed from any allegations of letting the property become intentionally overgrown — it simply didn’t have the funds to maintain it.

In 1969, the university continued to try to acquire the cemetery property. A bill introduced in the Legislature would have allowed for the cemetery to be condemned, absorbed into the university and built over. It was not the first bill of its kind, and like the others, the bill did not pass.

In 1970, the cemetery had another day in court, and for similar reasons. Harrison R. Kincaid, a cemetery lot owner, brought the Pioneer Memorial Park Association along with university President Robert Clark and former President Arthur Fleming, among others, to trial for a suit in damages amounting to $200,000.

Kincaid alleged “the Pioneer Memorial Park Association and its associates were purposely allowing the property to degenerate in conspiracy with the university so that it might be condemned and then declared open for sale and rezoning, resulting in the relocation of the burials.”

If true, it would make the process of obtaining the land much easier for the university.

In 1971, a judge ruled in favor of the defendants because Kincaid failed to provide sufficient evidence that a conspiracy was happening.

After 1971, the Pioneer Memorial Park Association “ceased to be active concerning the cemetery,” according to Oster, who wrote The Eugene Pioneer Cemetery.

As it turns out, four Medal of Honor winners had been buried at the cemetery, qualifying it to be on the National Register of Historic Places. Once it attained that designation, talks of the university buying the cemetery dissolved.

Kramer’s thesis explains that by the late 1990s “the needs of the university had also adjusted as land was purchased to the east of campus, shifting the focus away from the cemetery.” — Asia Zeller