A sense of humor is either the last thing to go or the first, but either way the death of humor is an epidemic these days, as well as a mortal loss, more speaking to the wretchedness of our hearts than the fracture of our funny bones. The muffling of laughter speaks to the real depths of our despair.

To wit, it appears that some among us are largely missing the message of Taika Waititi’s new film, Jojo Rabbit, an unusually charming love letter to tolerance and resistance in the face of things so hellish they threaten to saw your soul out of your body.

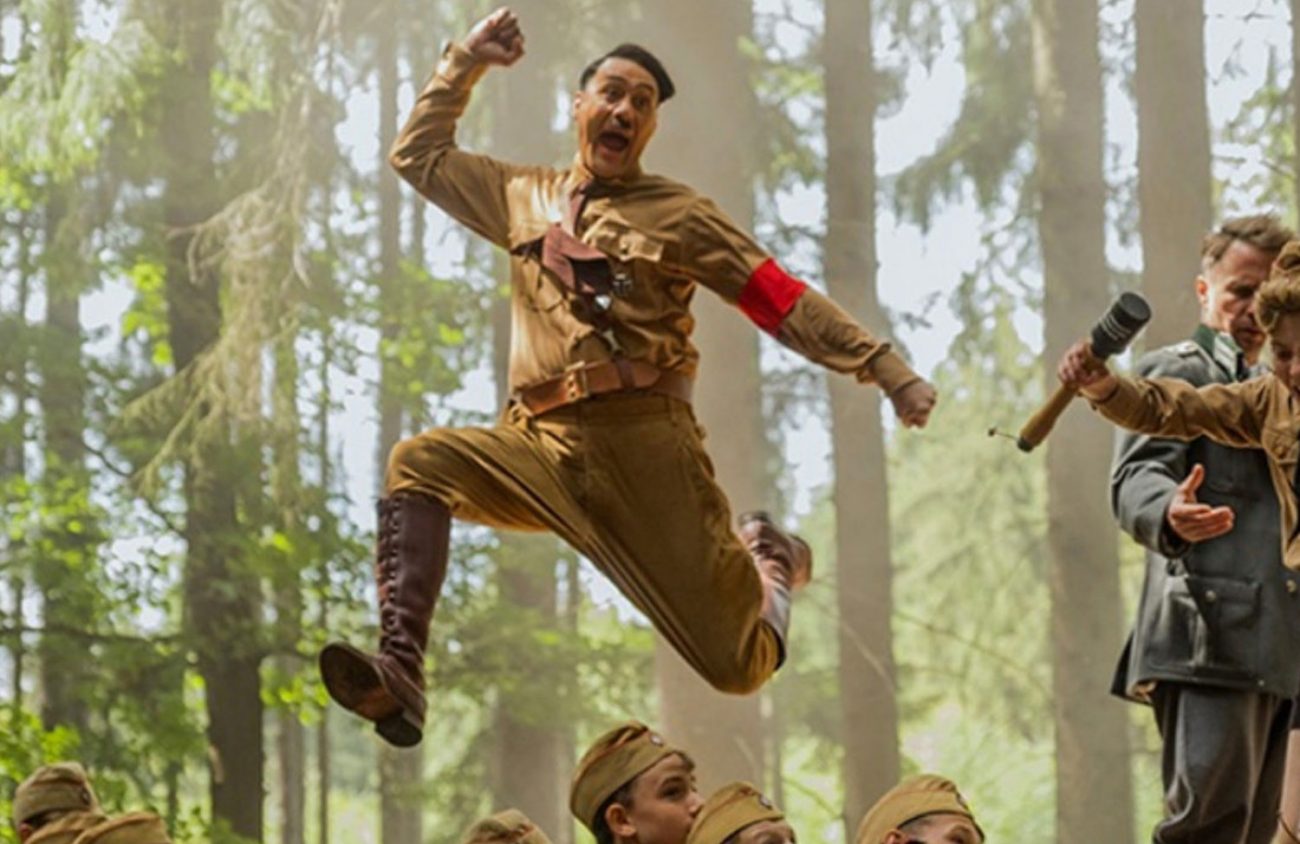

Yes, Waititi’s film is, in part, a broad parody set in the last days of Nazi Germany, and it takes wonky aim at Hitler (played by Waititi himself, in a brilliant comic turn), portrayed here as a loose-limbed avuncular character whose cheerleading for bigotry and hatred comes across as an absurdist inversion of Queer Eye antics.

Hitler’s physical presence — and this is no spoiler, as it’s immediately evident — is entirely imaginary, a consoling dream in the head of the title character, Jojo (Roman Griffin Davis), a 10-year-old misfit who yearns for the communal embrace of membership in the Hitler Youth. Jojo’s hatred of Jews is largely formulaic, an ambivalent bid to fit in with the winners.

Jojo’s fantasy of belonging to a good Nazi family is thrown into chaos when he discovers that his mother, Rosie (Scarlett Johansson), is hiding a young Jewish girl (Thomasin McKenzie as Elsa) in an upstairs cubbyhole of their apartment. Not wanting to jeopardize his family, Jojo keeps the secret, spending his evenings hilariously, and touchingly, questioning Elsa on the nature of Jewishness, all in hopes of compiling a manual useful to the Nazis.

Waititi’s 2016 film Hunt for the Wilderpeople was one of the year’s best, revealing a director who is comfortable not just combining genre elements but shattering them altogether. Similar to South Korean director Joon-ho Bong (Parasite, The Host), whose films can skip from tears to terror to wailing laughter in the same scene, Waititi — a New Zealander — employs things like slapstick, tragedy, melodrama and suspense with such ease that they disarm expectations, conjuring an atmosphere that is no less authentic for being entirely hypnotic.

In Jojo Rabbit, this fluid, hallucinogenic reality is less a carefree punk on Nazis than a channeling of Jojo’s understanding. Hitler’s larky goonery cues us into the fact that the film represents the boy’s perception of the world, and as such its cartoonish swirl becomes deeply terrifying and cosmically hysterical — kind of like life itself.

Though it hardly shies away from the horrors of the Third Reich, the underlying theme of the film is the persistence of love and understanding, both in the intimate sense of personal relationships but also in the grander (dare I say spiritual) sense of an achieved fellowship on Earth, one that extends acceptance and forgiveness when such things seem nearly impossible. Hence, along with the moments of broad satire, the heart-wrenching recurrence of Rilke’s poetry throughout the film, which cautions:

Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.

Just keep going. No feeling is final.

Don’t let yourself lose me.

These verses, which land with the force of awakening, are the surest indication of what Waititi is up to in Jojo Rabbit. The film, whose surfaces are so zany and irreverent, is at bottom a gesture of consolation, a lifeline for suffering souls in a world gone mad.

Beneath the madcap action, the goony characters and Wes Anderson scenery beats a big heart coursing with the stuff of life, against all odds and, often, in the throes of unspeakable crimes. In this sense, the film’s comedy is Shakespearean, functioning like a telescope instead of a microscope.

Beyond this, the movie is a technical wonder, great to look at and thrilling to behold, and the cast carries it all off exquisitely, no small feat considering the range of tones it strikes. As the kids in the eye of the storm, Davis and McKenzie are talented beyond their years. Sam Rockwell, one of the best actors around, gives a great performance as a bumbling, demoted party functionary.

But it is Johansson who’s most surprising. With an old-Hollywood comic flair reminiscent of such greats as Katherine Hepburn and Irene Dunne, she brings to her role as Jojo’s mother a defiant joy that refuses to buckle in the face of the evil it feels compelled to confront, at whatever cost. Her character is the incarnation of the spirit of healing that propels this oddly beautiful film. (Broadway Metro) ν