By Taylor Griggs and Henry Houston

Air pollution levels in Lane County have reached extraordinary highs this past week as a result of the nearby Holiday Farm Fire and other wildfires around the state and region. While providing shelter for people evacuating these fires has been the primary focus city and county officials, community activists point out that the people who had been unhoused before the wildfires are also in desperate need of shelter from the toxic air.

More than 2,100 people in Lane County experienced homelessness in 2019, according to a county Point-in-Time report. That number is expected to increase due to COVID-19’s economic impact and diminishing state and federal resources.

The city and county have provided some daytime and overnight clean air shelters for unhoused people during this latest crisis, and the state of Oregon’s wildfire preparation during COVID meant prioritizing hotels to avoid large congregation shelters. The Governor’s Office says local governments could work with homeless advocacy groups to find them shelter and use a recent law that allows groups like churches to provide shelter.

Many activists say it’s not enough, and mutual aid organizations have had to take on some of the work. And the delay in providing shelter for the homeless during toxic air quality levels pales in comparison to Portland, where the local government has relied on an office dedicated to homeless services and its community relationships, which has helped the area deploy shelters quickly for the unhoused.

But for the unhoused in the Eugene area who are stuck outdoors without shelter, they’re exposed to high levels of poor air quality, and the long-term effects are unknown due to a lack of research, according to the Oregon Health Authority.

As climate change continues, the future only looks worse.

Eugene’s Response

Nearly a week after the start of the Holiday Farm Fire, Eugene Mayor Lucy Vinis addressed the community’s concern about homeless people’s safety during hazardous air quality levels at the Sept. 14 Eugene City Council meeting.

“This week has been very hard. We have recognized that we have people living unsheltered under conditions of very poor air quality. We have worked very hard to find ways in which we can help people’s health in these circumstances,” Vinis said. “None of it is enough, we recognize that none of it is enough.”

Vinis said that the city will be moving forward with strategies recommended by the Technical Assistance Collaborative, a nonprofit consulting firm, in its 2019 report on how Eugene can better address homelessness.

These suggestions include the development of inclement weather preparation for unhoused people, but Vinis said that they weren’t prepared for an event as extreme as these wildfires.

Local Black Lives Matter activist and write-in mayoral candidate Isiah Wagoner addressed Vinis and the rest of the council during the meeting’s public forum, saying they should have been better prepared.

“If you know that what you’re doing isn’t enough, you need to be doing more,” Wagoner said. “You have failed us as a society and as a community. If you want to know how it feels to be unhoused, I advise all of you to sleep in your cars tonight and see how you like that.”

Toxic Air and Shelter Options

People living in poverty are at higher risk from wildfire smoke, OHA spokesperson Delia Hernández tells Eugene Weekly. That’s because they’re more likely to have pre-existing conditions, less able to avoid or protect themselves from smoke and more likely to lack housing.

When people are breathing outdoors, they’re at risk of breathing in particulate matter 2.5, which is the cause of most immediate health risk from smoke.

“The smallest particles are the greatest risk to health because they can reach deep into the lungs and may even make it into the bloodstream,” Hernández says.

She adds that PM 2.5 can affect lungs and the heart, and there are numerous scientific studies that link the particle to health problems such as nonfatal heart attacks, premature death in people with heart or lung disease and increased respiratory symptoms.

The long-term effects of prolonged exposure to PM 2.5 is unknown since more research is needed, but it could result in long term respiratory, cardiovascular and immune effects, she adds.

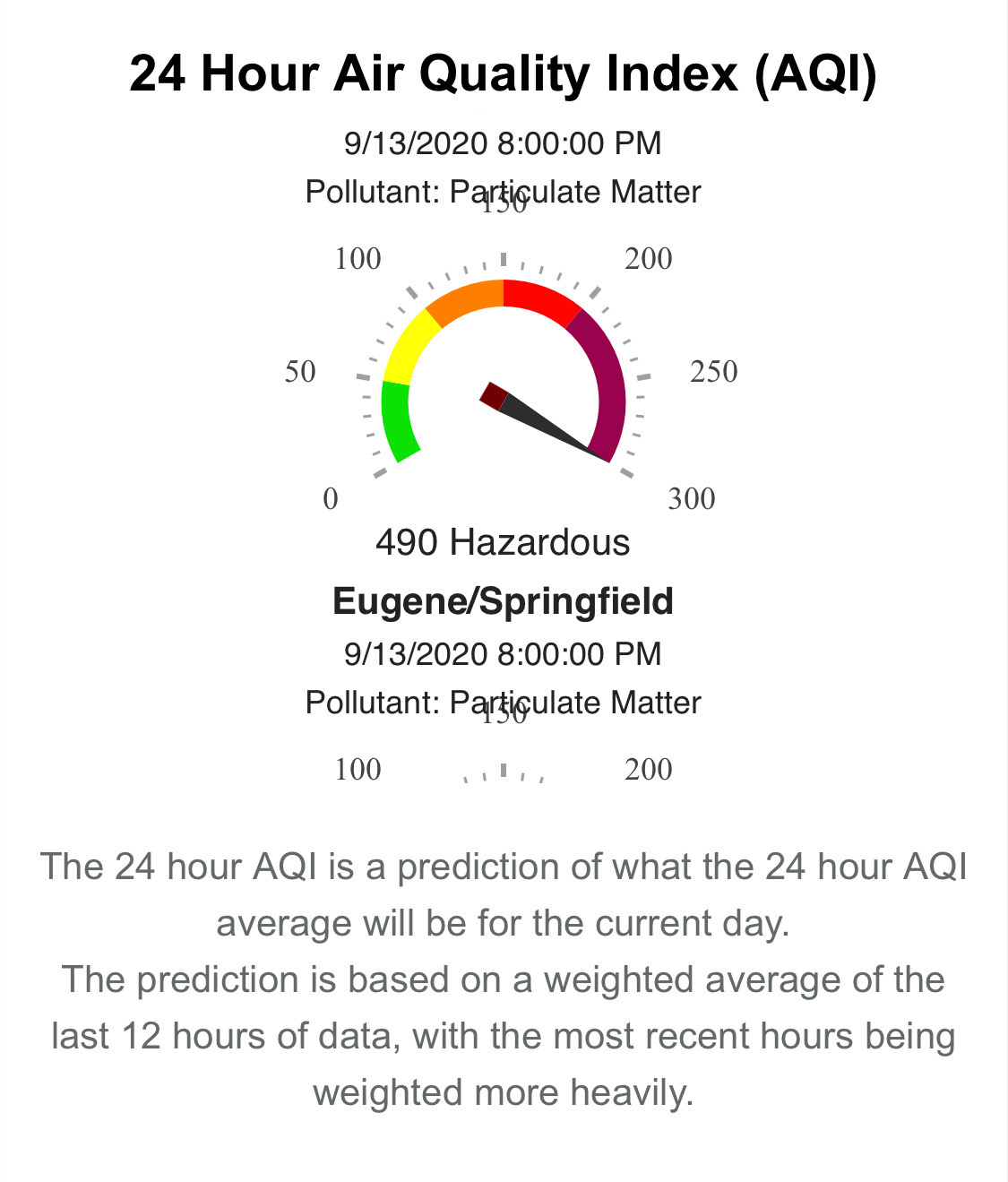

Eugene and Lane County have been working together to create clean air respite shelters since Sept. 9, a day after local air pollution reached 342 on the air quality index — categorized as hazardous — and the sky turned orange. These started as daytime shelters at the Hilyard and Petersen Barn Community Centers and the Lane Events Center.

On the city’s Facebook post about clean air overnight shelters, it said COVID-19 prevented the use of congregate shelters. But OHA tells Eugene Weekly that it did not say congregate shelters were unsafe. It provided risk management guidance to minimize the risk of spreading COVID-19.

According to OHA, it sent out a shelter guidance on Sept. 10 that said sheltering in place is ideal; hotels, dorms or small shelters should be prioritized over large settings; and officials should demobilize large congregate shelters as soon as possible and send residents to hotels, dorms or small shelters.

On Sept. 13, the county and city announced the Lane County Events Center would now host a 24-hour shelter for 15 people. However, the largest building at the complex is reserved for an Itty Bitty Boutique children’s clothing consignment sale.

At the Sept. 14 Eugene City Council meeting, Councilor Jennifer Yeh addressed demands for more clean air shelter space, and said that the city didn’t have enough demand to even fill those 15 spots at the fairgrounds on the first night it was open.

“If you have insight on how we can do better to reach this population of folks to get them into these spaces, we need that information,” Yeh said. “Clearly, we’re not reaching people if we’re not even filling 15 beds.”

On Sept. 13, nine people stayed at the events center shelter and 14 stayed the night after. The city says that it’s up to the White Bird Clinic to provide referrals to access this overnight respite center.

But Heather Sielicki, administrative operations coordinator at White Bird Clinic, says that she has been hesitant to even advertise the overnight shelter because the process has been so haphazard.

Sielicki says that she didn’t feel comfortable telling people to bring all of their belongings somewhere they might not be able to stay, especially after days had already passed with no provided respite after 8 p.m.

“It would’ve been really helpful to have this earlier, as soon as we saw that the air was toxic,” Sielicki says. “This is just one of many systemic failures in our city’s ability to plan and provide for its residents.”

On Sept. 16, the city of Eugene announced a second 24-hour shelter at 717 Highway 99 North, which will have the capacity for 16 people. This site also houses St. Vincent de Paul’s Dusk to Dawn program.

Black Thistle Street Aid, a health care mutual aid collective that works with Occupy Medical and is currently collaborating with Community Outreach through Radical Empowerment, has been working to help Eugene’s unhoused community through this air quality crisis.

Abbey Carlstrom, a member of BTSA, says that many homeless individuals don’t trust the city to deliver adequate resources or protect them.

“The city has made no effort to establish a trusting relationship with our unhoused neighbors,” Carlstrom says. “It has not laid any groundwork to do proper outreach in times of crisis or otherwise.”

Carlstrom says that while this severe wildfire event may be unprecedented, Eugene should have had some preparation for such crises and done more outreach to help the homeless community. City and county officials say they did as much as they could as quickly as possible.

“It benefits the city to have their sad excuses for relief efforts go unutilized,” Carlstrom says. She says she thinks that city officials care more about seeming virtuous to their wealthier constituents than actually helping the unhoused community.

BTSA, Occupy Medical and CORE Eugene have raised more than $20,000 dollars in an online fundraiser to help homeless people during this time. Carlstrom says that they have been able to place more than 30 individuals in hotels for four nights each, with the remainder of the money going to provide ongoing care for unhoused people with food, supplies and medical care.

Lane County government won’t comment further on its shelter options for the homeless other than what was shared on social media by the city of Eugene, which says the two governments are working together to establish clean air centers.

“Safe overnight shelter requires setting up qualified service providers and that process would likely take longer than the actual poor air quality event. The quickest option for offering indoor clean air space for people without indoor shelter was to make our existing community centers available during the day. We opted to make that available as soon as possible rather than wait,” spokesperson Devon Ashbridge says in an email, which was a similar statement to what was posted on social media.

Ashbridge says the county needs other partners to lead on additional smoke respite centers while the “county continues to lead on the wildfire and COVID emergencies.” She adds that the county distributed 300 N95 masks.

N95 masks prevent most wildfire smoke particles if fit tested and worn properly, according to Hernández of OHA.

American Red Cross spokesperson Chad Carter says its goal is to place as many people as possible in hotel shelters. The nonprofit put more than 2,400 people in hotel rooms statewide Sept. 14, but because of high demand and low availability in the Eugene area, providing for everyone in need of shelter is a challenge.

On Sept. 16, the American Red Cross opened a shelter at Churchill High School. Hours after the shelter opened, evacuees staying at hotels near the University of Oregon received flyers that said they would have to check out by noon Sept. 17. After uproar on social media, the American Red Cross and hotels worked out an extended stay for evacuees.

Air quality could get better soon should forecasted weather patterns emerge, says Travis Knudsen, spokesperson for Lane Regional Air Pollution Agency. But that doesn’t mean the air will clear up throughout the Willamette Valley; it could still be at high levels in certain locations (like Springfield or east Eugene) if rain happens, he says.

The high smoke levels have impacted how some government buildings can serve people seeking refuge.

On Sept. 8, the Bob Keefer Center and Willamalane Adult Activity Centers opened as smoke respite shelters. Two days later the buildings closed. Willamalane spokesperson Kenny Weigandy says the buildings were closed because its HVAC systems relied on pulling outside hazardous air indoors. He says Willamalane is working with community partners to install secure air purifiers to keep air quality indoors at healthy levels.

While the city of Eugene searches for shelter facilities, it focuses on finding large spaces that allow for social distancing and an HVAC system that keeps the indoor air quality at a healthier level than outdoors, says city spokesperson Sarah-Kate Sharkey. Eugene is working with the University of Oregon to monitor indoor air quality and is locating air purifiers for its shelters.

Knudsen says LRAPA has been tracking the air quality at the Hilyard Community Center, and it has had better indoor air quality compared to other facilities where the agency has an indoor sensor. The building might be sealed well and a good HVAC system and HEPA filter, he adds.

The State’s Response to Disaster

At the state level, preparation for wildfire-related shelter has been focused on evacuees staying in hotels to avoid an increase of COVID-19 infections.

At Gov. Kate Brown’s Sept. 14 press conference, Brown said OHA is helping with the Office of Emergency Management to make sure that housing provided is non-congregate care because of COVID-19.

OEM Director Andrew Phelps said OEM prepared for the wildfire season in the COVID era by avoiding a reliance on congregate shelters.

“Currently we have twice as many folks in non-congregate shelters, meaning hotels and motels, than in a congregate setting,” Phelps said. “We also have a lot of folks staying in RVs or staying with friends.”

EW asked the Governor’s Office if Brown is considering an executive order for increased 24-hour shelter support. The office’s spokesperson Charles Boyle says in an email that during the first special legislative session this year, the Legislature passed House Bill 4212, which allows local jurisdictions to OK shelters hosted by groups with at least two years experience.

“While we understand communities still face logistical barriers, such as staffing or funding constraints, the mechanisms in HB 4212 give local jurisdictions a pathway to expanding shelter capacity when needed,” he says.

According to the city of Eugene’s webpage on the legislation, groups must apply to open an emergency shelter. The deadline is Sept. 28, 90 days after Brown signed the law.

Although the city of Eugene is only accommodating up to 31 people a night after receiving a voucher from White Bird, Boyle says his understanding is that “the existing homelessness services system is working to accommodate people who were experiencing homelessness prior to the fires who are now being impacted by the smoke and air conditions.”

How Portland Responded

Compared to Eugene, Portland’s local government agencies reacted faster to providing 24-hour shelters.

In 2016, Portland and the Tri-Counties established the Joint Office of Homeless Services (JOHS) to oversee the delivery of services to people experiencing homelessness. When wildfires struck Oregon on Sept. 8, the office established a 24-hour shelter two days later.

On Sept. 10 when winds changed and smoke levels became hazardous in Portland, JOHS consulted with public health officials on the need to open a shelter, says Denis Theriault, the agency’s spokesperson.

Multnomah County has space for 200 people who are experiencing homelessness at the Convention Center and at the Charles Jordan Community Center in North Portland, Theriault says. The American Red Cross is also managing a shelter space in the Convention Center for anyone impacted by fire and smoke in the area.

He says after four nights and four days, those sites aren’t at capacity yet but the Convention Center is close to filling up. The JOHS also special ordered 40,000 KN95 masks when the forecast showed smoke levels would be high.

The Portland area was able to have an overnight shelter so quickly because the JOHS has a system for responding to severe weather, as well as the Multnomah County’s Emergency Management Department, he says. Usually responding to cold and snow, the offices can open hundreds of beds as quickly as possible in the same three buildings but can expand to other locations if needed.

And COVID-19 helped the office’s response, too. Theriault says the JOHS has a positive relationship with the owners of the Convention Center, the Charles Jordan and Mt. Scott locations.

“It’s taken so many hands working closely together to get help to those most in need,” Theriult says. “Homelessness is an emergency every day, whether we’re in a pandemic or watching our skies fill with poison. But thanks to a lot of hard work preparing for the worst, and an amazing amount of community support, we’ve been able to quickly help hundreds of our neighbors navigate one more crisis.”

Thinking ahead

The fires that overwhelmed the West Coast this summer were historic. But wildfires in this region will only grow as the impacts of climate change increase. More people will be displaced from their homes, and more unhoused people will suffer the effects of breathing in toxic air.

Sielicki says that the level of discrimination and stigma against unhoused people creates endless cycles of poverty. She says that this same stigma will soon transfer to people who evacuated wildfires and weren’t able to get back on their feet.

“We are in a lose-lose situation,” Sielicki says. “We criminalize the people who are unhoused so they become chronically homeless. How long will the empathy last for evacuees?”