On a media tour of Weyerhaeuser timberland 10 days after the start of the Holiday Farm Fire, a press information officer leading the trip says if you want to see what the Moon looks like, peer over at the side of the hill.

The hillside was filled with burnt tree stumps, scorched earth and smoldering spots — with a sea of smoke blanketing the sky.

The private timber plantation was just one of many to burn throughout Oregon during the historic wildfires that raged after the Sept. 7 windstorm. Although the wildfires in Oregon have sparked a call from the right for forest management, others say that a pro-timber narrative is the reason for some of the fires’ ferocity — because the Holiday Farm Fire burned mostly across private timber forests.

“It’s the legacy of forest mismanagement that is fueling the wildfires, along with climate change, which is the ultimate driver,” says Tim Ingalsbee, executive director of Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics and Ecology (FUSEE).

In the immediate days following the start of Oregon’s wildfires, President Donald Trump visited California, which also has been affected by wildfires, and criticized the state for a lack of forest management. On Sept. 14, Trump told reporters at an airport in Sacramento that trees that fall and dry on the ground are “like a matchstick.”

“If they’re on the ground longer than 18 months, they’ve very explosive,” he added.

Trump has long pushed for odd solutions, such as raking the forest floor — a statement he was ridiculed for the first time back in 2018. But national media outlets have contributed to a pro-forest management narrative, with the Washington Post running a Sept. 12 op-ed by former Oregon state Rep. Julie Parrish, a founding board member of Timber Unity Association. Parrish dismisses the idea that a wind event and climate change caused the fires; it was “gross mismanagement of Oregon’s forests,” she writes.

Ingalsbee says maybe Trump isn’t totally wrong about raking. It does address the primary hazardous fuel type like underbrush that can make wildfire spread. But the Holiday Farm Fire exposes the lie that logging prevents wildfire spread.

Ingalsbee says a wildfire can burn at a moderate intensity and easily wipe out a timber farm — and that’s what happened with Holiday Farm. He says the fire shot down the valley, moving east to west, which is a rare event.

“Like a blowtorch in a wind tunnel,” he adds. “The flames, embers, were moving horizontal.”

Ingalsbee says Holiday Farm and other Oregon wildfires also had a lot of the other climate change and weather-related ingredients — high temperatures, warm winds and drought.

After the fast warm winds died down, he says the flames then moved on to the timber farms, mainly Weyerhaeuser’s. The timber farms were “the accelerant for the extremely rapid rate of spread.”

“Forest management did not stop wildfire spread. It did not lower its intensity or severity,” he says.

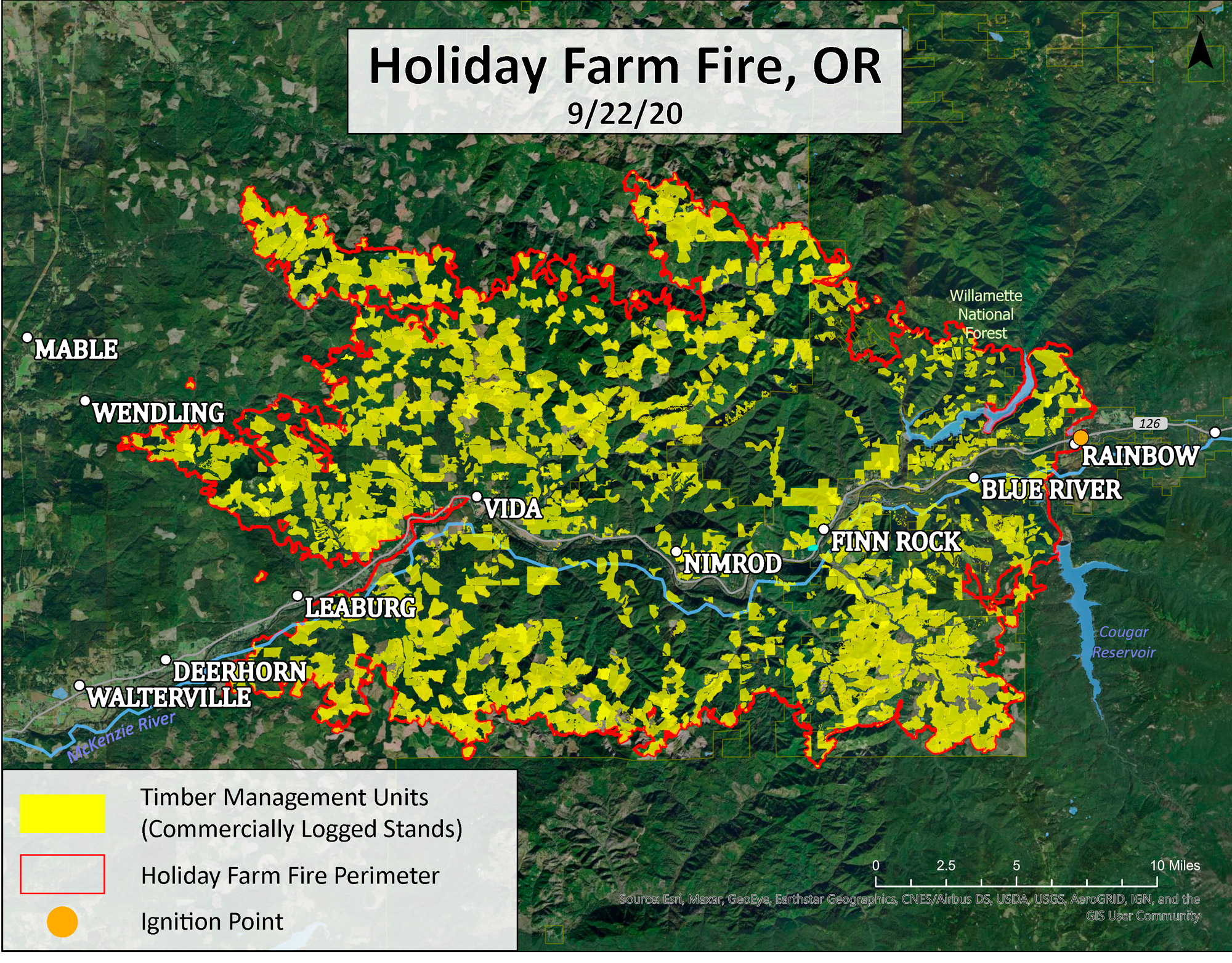

Enlarge

Image credit: FUSEE

Using GIS, FUSEE created a map with the perimeter of the Holiday Farm Fire atop a layer of the geographic area. The map shows this fire consists mostly of commercially logged stands. According to Mason, Bruce and Girard, a Portland-based forestry and natural resources consulting firm, 92,600 acres owned by private large forest companies in Lane County burned — nearly 60 percent of the fire’s acreage.

How the fire burned on public lands is an extreme contrast to how quickly the fire burned on private land, Ingalsbee says adding, “It takes a really hot fire to completely kill all trees in an old growth forest.”

In 2018, a study co-authored by Christopher Dunn of Oregon State and Harold Zald of Humboldt University examined the 2013 Douglas Complex Fire. They found that weather was the primary factor in determining fire severity but concluded fire severity was greater on private plantations than in older public forests.

On Sept. 16, 2018, pro-logging organization Oregon Forest Resources Institute published a rebuttal on its website. The group’s director of forestry Mike Cloughesy said the only conclusion he drew from the study was that forest management practices “may contribute to increased wildfire and tree mortality in the plantations they studied.”

He added that private landowners don’t need a study to remind them that younger trees are killed by fire, though firefighters told him it’s easier to control wildfires on private timber farms.

One area where pro-logging and pro-environment perspectives agree is that nature interacts differently with old growth and timber farms. Ingalsbee says wind speeds are twice as strong on a clearcut. But wind speeds are halved when they hit an old growth forest. “A lot of that wind kind of bounces off the upper canopy,” he says. “And then you got these big tree trunks that also block the wind.”

Wildfire spread happens on surface fuels, like downed dead needles, limbs, grasses and young trees that have a diameter less than three inches, Ingalsbee says. “That’s all that these young plantations are: just small diameter fine fuels right down to the ground,” he adds.

After the Holiday Farm Fire, Ingalsbee says the scenery along the McKenzie Valley is going to be barren.

“Folks should prepare themselves for blackened, barren hillsides bordering the river,” he says. “It’ll be like going back in time to the 1980s — or whenever those clearcuts were first put in place. It’s going to be ghastly for folks.”

But with the pro-timber narratives, Ingalsbee says companies could influence Congress to allow them to go into public forests, especially if Trump loses the election and becomes a lame duck. Private timber companies’ investments have “gone up in smoke,” he says.

“There will be a mad lust to go on public lands. Any burned forests on public lands, they will be crazed to get access to that,” he says.

If private timber companies do get access to the public lands, he says they’ll make a bigger mess of the forests. “The river itself is going to run red this winter when the rains come down and wash off the barren slopes of those burned clearcuts,” he says.

It’s possible the area won’t resemble the moon — it could offer a glimpse of the desolate landscape of Mars.