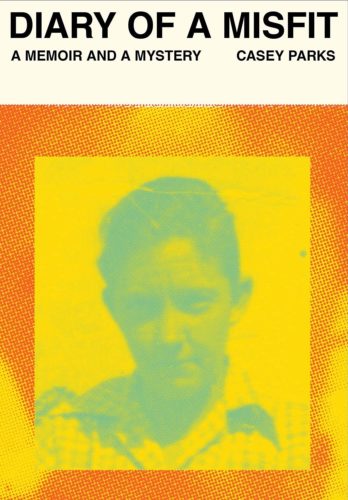

The best books are the ones we don’t want to end. This is how I feel about Casey Parks’ recently published book Diary of a Misfit (Alfred A. Knopf). In a memoir that unfolds as a mystery tale, Parks intricately weaves together the stories of two parallel lives that diverged in radically different ways. As a journalist, Parks relies on interviews and research to craft the story of a transgender man who lived his life as a self-proclaimed “misfit” in rural Louisiana in a time long before anyone spoke of gender identity or pronouns. The second story is hers — she writes of her experiences growing up in a fundamentalist family and coming to terms with her own identity as a lesbian.

Parks writes poignantly and brilliantly about growing up as an outsider, reckoning with family and love and grief, and the perpetual search for meaning in this increasingly complex thing we call life. In giving Roy the space to be seen, Parks creates refuge for all of our inner misfits.

Parks’ memoir is receiving critical acclaim and has been featured in publications across the country, including the prestigious NYT Sunday Book Review. Though she grew up in Louisiana, Parks has lived in Portland for nearly 20 years, working as a reporter for The Oregonian and now for The Washington Post, where she covers gender and family on the social issues team.

In full disclosure, I’m also from Louisiana, work in journalism and am writing a memoir. For all those reasons, I jumped at the chance to chat with Parks about her book. A piece of our conversation follows, and it’s been edited for length and clarity.

Your book has been out for several weeks now. It’s receiving critical acclaim and readers love it. What do you like hearing best from readers about their experience with your book?

I’ve heard from a lot of people, but probably my favorite readers are gay people in their 70s and 80s. One woman who’s 89 wrote to me that she had been with her partner for 65 years. And she just came out last year. And when she was growing up, she didn’t have books that had people like her. She didn’t have TV shows to watch. And she realized that she could have had a life like Roy’s in some ways. But even though she had to stay in the closet, she did have someone that she loved. And it’s just amazing to me to connect with people from those older generations. Because I do think it’s a book about how things have changed in — you know, in some ways, they’ve gotten better. And in some ways they’ve gotten worse, but I don’t know, maybe I’m gonna write a second book about this 89-year-old woman in Idaho, because she’s really fascinating to me.

You poignantly showed the complexity of people and relationships — especially between a child and a parent when the parent is anything but ideal. But as a reader, I came to care greatly for your mother and I cried when she died. For her loss and for your grief. How were you able to show the reader the love through the pain?

Empathy for her. She was young, and she went through trauma. When I decided to write about my mom, I knew I wanted to render her as specifically as possible. And the thing is, some days, she was really exciting and really loving. And some days, she slept for weeks on end. Or she was mean, or she was angry. It was confusing as a child. But as a writer, I just wanted to capture her as she really was and she wasn’t just one thing.

You also showed us the complexity of Roy. What do you like best about Roy? How do you feel about Roy today?

For many years, the things people told me about Roy were pretty simplistic. They told me he mowed lawns for a living, and then he played the guitar. But they tended to talk about him like he was a perfect angel. Like, he never did anything bad. He never got angry. He was just innocent. I think they meant well by doing that. But I think it also kind of revealed that they didn’t really know him. Human beings aren’t perfect that way. And I wanted to find someone who really knew Roy and all of his complexities. So my favorite thing that I learned about Roy is from two people who went to church with him where they sat together in the back pew. They told me that he loved playing dominoes, but he was competitive. And if he lost a game of dominoes, sometimes he’d get up and he’d throw all the dominoes out of the window. And they were cracking up as they told me, and I laughed a lot, too. And it just made me see him as a real human who got angry when he lost. I can see myself in that because I also am extremely competitive.

In an interview with Slate you mentioned that you never intended to write a memoir. Now that you’ve done it, how do you feel about it now?

I was really scared to put my own life out there. It’s not something I enjoy as a journalist. I mean, I like writing about other people, not myself. But I think putting myself out there and being vulnerable allowed other people to see their experience reflected and I think they’re coming back to me with their own vulnerabilities of what it was like to live in the closet or to be shunned from their homes and that makes me feel less alone and also makes me feel like it was worth writing.

You’re a reporter. And your job is to ask good questions that reveal information and solicit insight and emotion. What are the best questions you asked of yourself in writing this book?

I tried to ask myself why I did certain things and what did I really feel? Not, what did I want myself to feel for the sake of the narrative. Not, what would be the funniest version of this or the most amusing version? But what really happened? And what did that really feel like?

Toward the end of the book, you write, “I wondered how the stories we tell ourselves shape the people we become.” Do you think we can change our stories? Our inner narrative?

I hope so. At the beginning of my work on the book, I was lying to myself, and thinking, I don’t care about Louisiana, Louisiana can’t hurt me. I’ve left this place behind. And I’m only here because I want to extract the story from it. When I left Louisiana, I told myself that everyone there hated me and didn’t want to love me. And I learned that wasn’t true. Lots of people in my family wanted to love me, but I was the one standing between us. And by the end, I think I’ve made my peace with the idea that this place will always be a part of me, and will always shape me. But it’s really hard to change your inner narrative, and I admire anyone who does the work.