In the past five years, the city of Eugene has used 72-hour notices to evict unhoused people camping on public property more than 7,000 times, ordering them to move under threat of losing their possessions or paying a fine in court.

Oregon law requires cities like Eugene to seek help for the people they send packing. The law directs cities and counties to alert a social service agency each time they issue a notice and force a homeless camper to move.

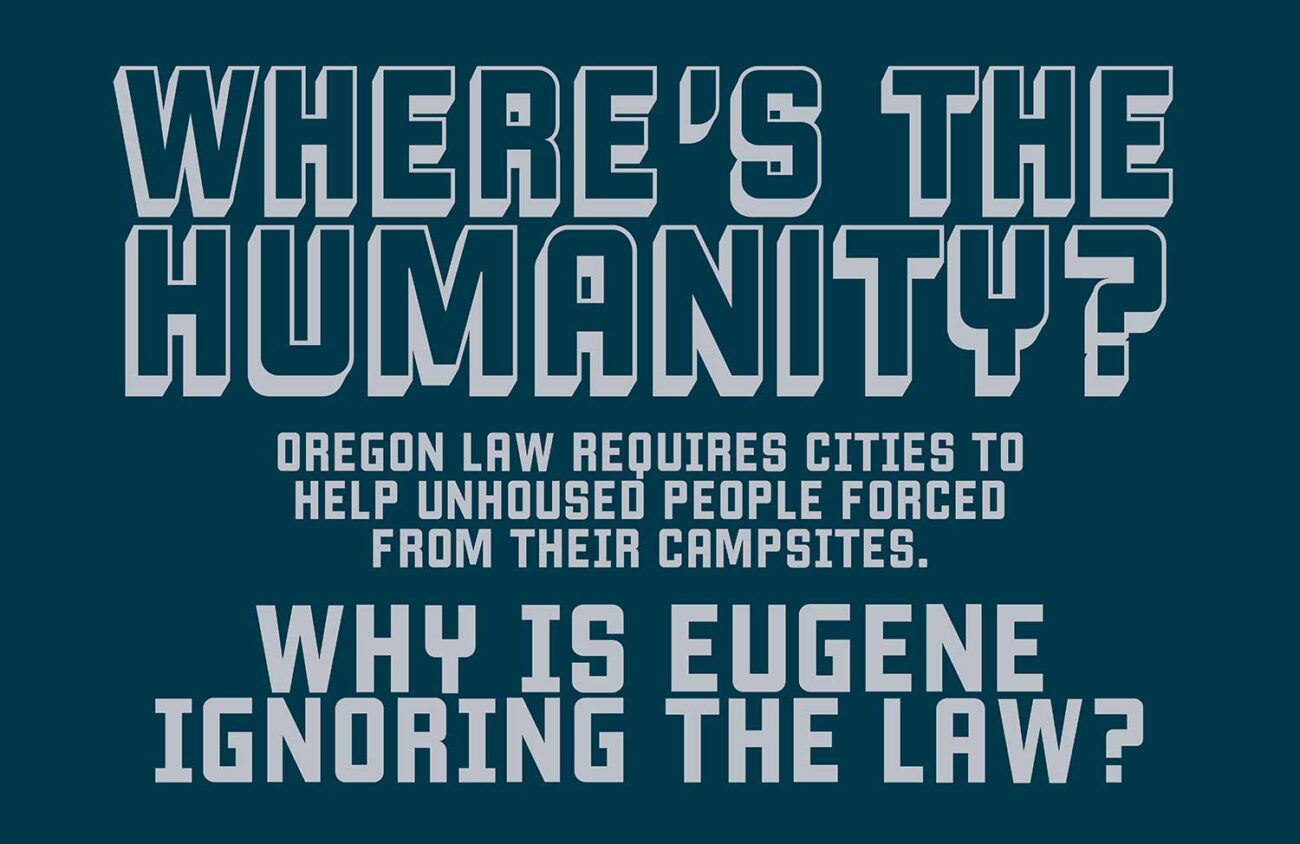

It’s been state law for nearly 30 years. Yet Eugene ignores this law daily and shows little signs of complying any time soon.

City officials acknowledge they rarely, if ever, notify social service agencies when they evict unhoused people camping on public property. Social service agencies say they receive no alerts from the city, despite the requirement in law.

Eugene officials say they don’t follow state law because they fund ongoing outreach services to unhoused people whether or not they have received a notice to pack up and move their camp.

But social services organizations dispute the idea that the city is providing adequate assistance, especially when the city compels homeless campers to move.

White Bird Clinic’s Navigation Empowerment Services Team (NEST) has a contract with Eugene to provide outreach services to unhoused people.

Theresa Boudreau, NEST’s interim coordinator, says the outreach program would be far more effective if the city alerted her organization where and when they have evicted an unhoused person from a camp.

“We cannot keep guessing where our clients may or may not go, who or where [they] may or may not get swept and provide a continuum of care that will actually make a change in our unhoused crisis,” she says.

Mayor Lucy Vinis declined to say whether she was aware Eugene officials were not following the law when it came to notifying social services agencies.

“I am aware of our efforts to address homelessness in this city and the challenges that we face. And I rely on the staff to do that work,” Vinis says. “I’m at a policy level — a much higher level — I am not involved in the day-to-day operations of the city.”

Vinis also declined to say whether she believes the city should comply with the law. “I believe the city has an obligation to address homelessness in our community to the best of our ability,” Vinis says.

City Manager Sarah Medary is responsible for overseeing city policies. She did not respond to Eugene Weekly’s request for an interview.

Since 1995, Oregon law has had requirements on how cities can evict unhoused people who are camping on public property. For example, a city must post a 72-hour notice before removing an unhoused person from a campsite on public property. (The 2021 Legislature increased the warning time from 24 hours to 72 hours.)

Oregon law also requires cities to develop a policy that “recognizes the social nature of the problem of homeless individuals camping on public property [and] implement the policy as developed, to ensure the most humane treatment for removal of homeless individuals from camping sites on public property.”

Here’s what the law says about providing services to people the city has swept from their campsites:

“When a 72-hour notice is posted, law enforcement officials shall inform the local agency that delivers social services to homeless individuals as to where the notice has been posted. The local agency may arrange for outreach workers to visit the camping site that is subject to the notice to assess the need for social service assistance in arranging shelter and other assistance.”

Former state Sen. Frank Shields, a Portland Democrat, helped write the 1995 law requiring cities to take a proactive step toward connecting unhoused campers with social services if they’re forced to move.

Shields says the Legislature wrote the law specifically to guarantee social service agencies could be present to help. Shields says he’s distressed that the city of Eugene is ignoring the law.

“They ought to be ashamed of themselves,” Shields says. “Where’s the humanity in that? Eugene is supposed to be known as a very progressive city. What’s progressive about this?”

The city has faced criticism that it’s been increasing the criminalization of homelessness.

On May 24, the Eugene City Council voted to update its anti-camping ordinance, compelled by a state law meant to protect unhoused people from criminal consequences for camping on public property when they have no other option.

But the city rewrote the rules without making it clear where people could legally sleep outside, and further criminalized homelessness by increasing fines and adding jail time in some instances.

Meanwhile, city officials have increased pressure on the unhoused in other ways.

Eugene officials quickly found a way to dodge the 2021 state law increasing the warning time to 72 hours before a city removes an unhoused camp.

The law requires that “established camps” receive 72 hours’ notice, so the city invented a new category for camps in October 2021: “non-established camps.” The city says these camps have been in place for less than 24 hours, making them exempt from the law. Instead of 72 hours to move, Eugene only gives “non-established” camps two hours.

Records show city workers have issued more than 1,400 of these rapid eviction notices since the law changed [See “Fast and Furious,” EW, April 13].

City officials defend their decision to ignore the law. City spokeswoman Cambra Ward Jacobson says in an email to EW that the city pays for outreach services that allow nonprofit organizations to look for unhoused people who might need help with finding shelter and other resources.

“By funding street outreach services to the unhoused, including those living in campsites that are posted for cleanup, the City is working to actively connect people with services instead of passively expecting that connection to occur as a result of a notification,” Jacobson’s email says.

University of Oregon law professor Sarah Adams-Schoen, who researches state and local government law, says the language of the statute is mandatory and that it seems there’s only an exception if the city has a more protective policy.

“The whole point of the Oregon statute is to protect people who are really vulnerable, and it creates a duty,” she says.

City spokesperson Kelly McIver points to the city’s contract with White Bird’s NEST program as an example. The city has provided $200,000 to NEST a year in each of the last two fiscal years, he says.

NEST’s Boudreau says her organization’s teams go out five days a week for about four to five hours looking for unhoused people to assist. Boudreau says NEST will make contact with clients multiple times to provide case management, but, when camps are suddenly moved, it has to track them down again to continue that assistance.

Boudreau says the city provides no information about where workers have posted notices for unhoused campers to move. If NEST had this information, she says, outreach crews could do far more to support people by helping them keep their belongings and find shelter.

“We try to be as preventative as we can, but we can only do so much with the tools that we have,” Boudreau says.

McIver also points to another White Bird program, CAHOOTS, the mobile team that’s dispatched through police non-emergency lines and serves as an alternative to police response for nonviolent crises

CAHOOTS Program Coordinator Arlo Silver says that the organization does not receive any alerts from city workers when they force unhoused campers to move. Silver also says CAHOOTS wouldn’t participate anyway.

“It is against our values to assist in sweeping camps in this way,” Silver says in an email. “In practice, being a default ‘resource’ in these situations simply makes it easier for the city and for the police to justify displacing people, because they can point to CAHOOTS and say we will take care of the situation.”

McIver also says ShelterCare is one of the agencies the city funds to provide street outreach services. But a representative from ShelterCare says the housing and behavioral health agency does not do street outreach.

“We do not have a street outreach team,” ShelterCare development coordinator Alyssa Gilbert tells EW. “We specialize in permanent supportive housing.”

City officials point out that they provide campers with a notice that tells them where they can locate social services and shelter on their own.

But Heather Marek of the Oregon Law Center says a piece of paper with a list of resources cannot replace the timely help the law intends to provide unhoused people. Social workers are specifically trained to help people in traumatic situations navigate accessing resources, she says.

Marek says her unhoused clients often don’t know where they can go to sleep or get help in Eugene.

She recalls an unhoused person who uses a wheelchair describing police telling her she could move to Eugene Mission, a shelter that was miles away.

“When they relate to me the traumatic event of their sweep, I frequently learn that they specifically asked city staff where they can go and are offered no options, or they tell city staff about their disabilities and ask for help but are offered no assistance,” Marek says.

Blake Burrell, the Eugene Human Rights Commission’s Homelessness and Poverty Work Group co-chair, says without real-time data on shelter capacities, he wonders how city or outreach workers could know which shelter a camper could go to.

“If the City of Eugene did inform local agencies when and where notices are posted, some agencies may conduct outreach, and in that instance, those organizations may be able to provide more accurate information on programs and daily bed unit inventory to individuals impacted by clearances,” Burrell says in an email to EW.

Ashley Smith and Jason Maloney, a couple who has been living unhoused in Eugene for more than a year, say they know the experience firsthand.

Smith and Maloney say that in October last year, they were camping in Amazon Park when city workers gave them a 72-hour notice to remove their tent. Maloney says they stayed right up until the deadline. “We always run it to the end because we don’t have anywhere to go,” Maloney says.

Smith and Maloney say that before they could move their camp, it started pouring rain. They huddled together in their tent, squeezing into the corner of it that was still dry, and fell asleep.

They say police officers woke them up the next day and issued them tickets. Records show police on Oct. 25, 2022, ticketed Smith and Maloney for violating park rules. The next day, records show, police again charged them with violating park rules and added a criminal trespass charge for each of them.

Smith and Maloney say it would have been helpful to know where they could have found shelter before that rainy night left them with the violations.

But they say finding a shelter that’s nearby, open, accepts couples and has available beds is difficult — not to mention lugging their belongings.

Smith says that if Eugene officials had alerted social workers to their location, they would have had a greater opportunity to find shelter.

“If there was a system in place that would facilitate something like that, it would be really beneficial,” Smith says. “I don’t want to spend the rest of my life in a tent on a street.”

EW asked Vinis if she thought having the city follow state law would provide more support to unhoused people.

“On a local, county, state and national level, more robust services would help people who are homeless,” Vinis said.

Vinis declined to say whether she believed the city should change its approach to the notification law. City officials did not respond to EW about whether the city intends to start following the law.

But if the city continues to ignore the law, what’s the remedy?

UO law professor Adams-Schoen says, generally speaking, someone could take legal action to make the city follow a state law. “People can seek a declaratory judgment from a court that, essentially, tells the city it isn’t complying with the law. Another tool is the writ of mandamus, which is used to get a court to order a local government or any other governmental entity to do its duty under state law,” she says.

“Although the writ of mandamus is not always an available remedy, it is most effective when the legal duty is clear, like it appears to be under this statute.”

Marek says that the state law is meant to ensure cities are treating unhoused people humanely and recognizing the social nature of homelessness, as the law requires.

“But what we see is that [when] people are swept,” Marek says, “they’re pushed into places that are less safe and secure on the fringes of the city instead of getting connected to the shelter and services that could actually help better their situation.”