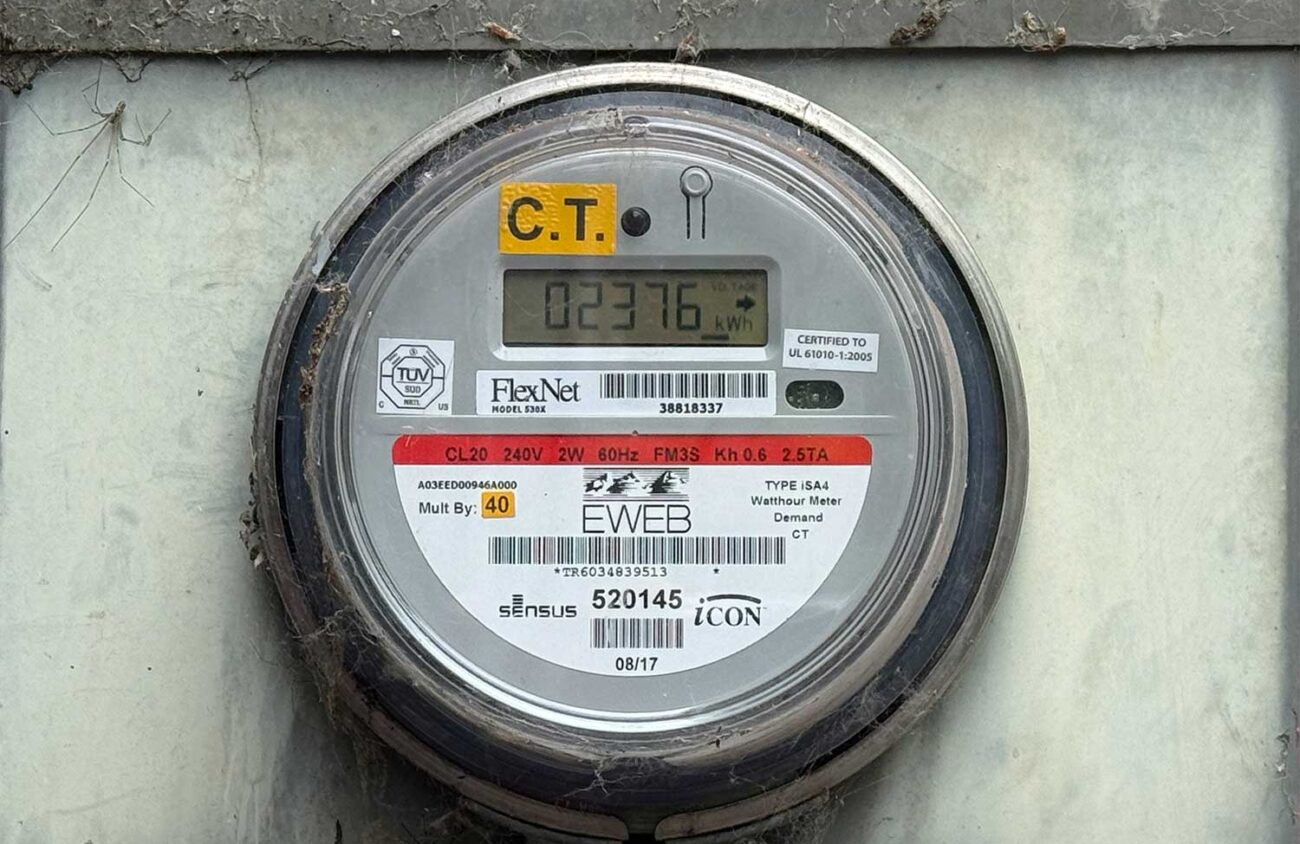

In function, smart meters do the same thing as legacy analog meters — collect and report data on water and electricity. But several homeowners have complained that Eugene Water and Electric Board’s smart meters are “dirty electricity” and have refused to let EWEB install them.

EWEB has said those who refuse the meters will have their homes disconnected from its electrical service. Twenty Eugene residents are now seeking an injunction to prevent EWEB from installing smart meters and from disconnecting residents from their power.

There are 91,140 smart electric meters and 50,373 smart water meters installed on homes across Eugene.

The “smart” part of the smart meter is just a radio — which operates between 900 megahertz and 2.4 gigahertz frequency bands — that remotely sends live data on a building’s water and electricity usage in real time to EWEB’s headquarters, allowing for remote disconnection and reconnection.

These are very similar to the frequencies emitted by all cellphones, wi-fi networks, baby monitors, cordless phones and other wireless networks and devices. And the meters transmit those frequencies in short bursts of 100 to 120 milliseconds, which throughout the day add up to about six minutes, according to a 2011 study completed by EMF & RF Solutions based in Encinitas, California.

According to a lawsuit against EWEB and its general manager Frank Lawson, filed May 24 by Damascus-based attorney Steve Joncus in the U.S. District Court, three of the plaintiffs who have refused the new meters say they have already had their power disconnected, and are still waiting for it to be turned back on.

Joncus says they are hoping to receive a preliminary injunction (which would last throughout the duration of the case) to block EWEB from disconnecting electrical services from anyone else. “I think it’s atrocious that EWEB is using its power to cut off people’s electricity,” he says. “These things are dangerous.”

EWEB maintains that customers cannot choose their own model of meter and will disconnect electric service from anyone who refuses this customer service policy.

“The meter is just like the pole in your backyard, and the transformer and the wires. That’s all EWEB-owned equipment.” EWEB Communications Specialist Jen Connors says. “If that customer were to continue to refuse to let us access our equipment, then we would start a process where we would disconnect them.”

That live, real-time monitoring has an opt-out clause. If you prefer to not send the data in real time, you can tell EWEB to turn off the radio signal from the smart meter. This means EWEB must conduct a manual meter read every month and send out a truck to all the houses with the smart radio signal turned off.

Those greenhouse gas emissions from the EWEB fleet add up quickly, and EWEB says it’s antithetical to its eco-friendly goals.

Already installed on over 96 percent of the homes within Eugene since the switch began in 2018, Connors points out smart meters are the industry standard and have been installed on over 120 million homes in the U.S.

EWEB can receive updates from every home in Eugene every 15 minutes, and can even remotely turn power back on that has been disconnected for nonpayment.

Without the meters, EWEB Climate Policy Analyst and Advisor Kelly Hoell says that EWEB would be unable to fold in more renewable energy sources into its energy portfolio. “We really can’t address climate change or work towards a low carbon future without a smart grid, right?” Hoell says. “And a smart grid requires smart meters.”

With renewable energy comes variance in the output it can produce. There’s only so much sun in Oregon during the winter months, and there’s only so much wind that blows at night. These sources vary by season, time of day and even weather patterns.

“As the grid as a whole is trying to integrate more variable sources, we need technology that can match that variable supply with the variable demand in real time,” Hoell says. In the past, EWEB could just buy some natural gas and oil from wholesale energy producers.

With real-time, variable supply matching, EWEB can ramp up its wind, solar and hydroelectric plants to better match the demand.

Kathy Ging, a longtime Eugene resident, says she worries about the supposed health effects from the electromagnetic frequencies (EMF) the meters pulse when sending data to the utility company.

Ging claims that a link exists between a high volume of EMF bursts and electromagnetic hypersensitivity (EHS), a condition that, according to Ging, causes a coterie of symptoms such as nausea, headache, fatigue, stress and burning sensations, among many others.

“There’s already too many microwaves in North America,” Ging says. “We don’t need more microwaves going through people’s houses.”

Faced with being told her power will be disconnected, Ging says her home now has a smart meter.

Sabrina Siegel, one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit, says she suffers daily from EHS and claims she can feel people’s smart meters in her own home. “It makes my life unlivable — I can’t really function at all,” she says.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there is no scientific basis to link EHS symptoms and exposure to EMF, and EHS isn’t considered a medical diagnosis. While not suffering from EHS herself, Ging says she almost became epileptic after using her cellphone for over 25 years. She says she has taken several steps to keep EMF and RF out of her home.

Although she still has a wi-fi router in her home and has owned a cellphone since 1990, Ging says she is looking into installing EMF shielding in her home and Stetzer filters, which supposedly short out high frequencies like those from a smart meter.

EWEB emphasizes that everything it does is strictly regulated and its smart meters meet the highest standards of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which monitors and controls standards surrounding EMF and RF.

“According to the FCC, they’re safe, and the emissions that are the radiofrequency emissions from smart meters are well below the safety standards, well below a cell phone and many other regulated devices,” Connors says.

EWEB Chief Energy Resource Officer Brian Booth explains that opponents claim smart meters create “dirty electricity” because they have a digital switching power supply. “That similar logic would apply to any DC power supply in your house,” Booth says. “If you plug in a cell phone charger, alarm clock — anything.”

This story has been updated including to reflect Kathy Ging says she is not epileptic but “a ‘white strobe light’ was in my head nightly when I lay down to sleep.” And she was told she was possibly on the edge of seizures.