I’m not the world’s biggest Motörhead fan, but even I can’t even see the name “Lemmy” without seeing that creased brow and hearing “The ace of spades! The ace of spades!” in my head. Motörhead is universal; Motörhead is monumental. Motörhead’s Lemmy is as deserving of a documentary as any musician who’s been doing his thing for more than 30 loud years.

The list of musicians who appear in Lemmy to praise — and tell incredible stories about — the man born Ian Fraser Kilmister is in itself the story of the influence of Motörhead: The members of Metallica. Scott Ian from Anthrax. Mötley Crüe’s Nikki Sixx, whose band clearly didn’t think up umlaut abuse on their own. Joan Jett. Dave Grohl, who records a track with Lemmy and relates a highly amusing anecdote involving Lemmy’s supposed feud with the singer from The Darkness. Billy Bob Thornton. Ozzy Osbourne (Lemmy wrote the lyrics to “Mama I’m Comin’ Home”). Henry Rollins. Alice Cooper. Slash. Jarvis Cocker.

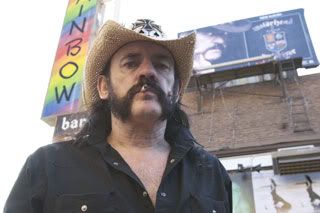

Lemmy is a fascinating, slightly overlong, almost-warts-and-all documentary about Motörhead’s bassist/lead singer and easily best-known member, he of the long hair, intense facial hair, Johnny-Cash-gone-punk all-black uniform and unforgettable, tattered voice. Lemmy is in his 60s and still plays with Motörhead. He sits at the Rainbow Room, on L.A.’s Sunset Strip, playing trivia on the Megatouch and drinking Jack & Cokes. Fans, unsuspecting, are in awe when they see him at the end of the bar. There is no mistaking Lemmy for anyone else. When Lemmy can’t find what he wants in L.A.’s Amoeba Music — the Beatles mono box set — the owner gives him her personal copy. People love this man, as Lemmy demonstrates, warmly and entertainingly, again and again.

The personality that emerges from the stories, and from Wes Orshoski and Greg Olliver’s film, is quietly affable, vaguely mysterious and sometimes perplexing. The filmmakers soar through Lemmy’s life, from his early bands to his time in Hawkwind to the beginnings of Motörhead to today, when Lemmy still plays with Motörhead and also with the rockabilly The Head Cat. Lemmy’s a fairly quiet person, but his presence is immense. When he does talk, he’s dryly funny and entertainingly observant (and extremely British in his sense of humor). A scene with his son turns surprisingly sweet and sentimental, even as the story of how Lemmy came to have a son is completely ordinary and less than romantic.

Orshoski and Olliver spent three years making Lemmy, and their dedication takes us to visit the man who makes Lemmy’s intricate boots; to his old school, where kids gleefully break into “Ace of Spades”; to Lemmy’s small, cluttered apartment near the Sunset Strip. Mementos and gifts from fans pack the space, but nothing is as disconcerting as Lemmy’s collection of Nazi memorabilia.

Flags, knives, uniforms — Lemmy says he just likes how it looks. He’d be a terrible Nazi, he says, because he’s had several black girlfriends. It’s a unsatisfying response to a weak question, and Olliver and Orshoski seem reluctant to press Lemmy on the topic. What about the Nazi aesthetic so appeals? How does Lemmy reconcile the attraction with the association? “I’m an atheist and an anarchist. I’m anti-communism, fascism, any extreme,” he once said in an interview with Chuck Eddy. He’s addressed the topic before, which makes it hard not to feel that here, Orshoski and Olliver are tiptoeing too lovingly around their star. (Outtakes of him telling them to get out of his face, on the other hand, are a crudely amusing credit-sequence bonus.)

Lemmy is a straightfoward documentary made absorbing by the tough shell and surprisingly low-key demeanor of its subject. Lemmy’s funny, sharp, remarkably ego-free and impressively candid. His romantic history is spotty at best. He wears tiny shorts in the summer and has a lot to say about ’70s drug snobbery, Little Richard and whether his son’s mother preferred John or Paul. Olliver and Orshoski clearly made this movie as fans, but it’s not only for fans. It’s a portrait of a metal god who is, as Billy Bob Thornton puts it in the movie, “part rock star and part guy who works at the car wash.” As celebrity portraits go, this one couldn’t be more welcome, even if Olliver and Orshoski get a little indulgent with the performance footage at the end.

To the crowd’s delight, Motörhead was in attendance at the SXSW screening. I took exactly one note during the brief and entertaining Q&A: When asked who he would like to play him in the movie of his life, Lemmy responded, deadpan as ever, “Helen Mirren.”

—

Lemmy does not yet have a release date, but I hope it gets one soon, because I want to watch it again.